Slavery in the courts

Butts v. Penny

(1677)

A crucial English Common Law case to define African slavery, and to create mechanisms to enforce ownership and recover debts related to slave sales. Over the following decades, the English courts became a battleground over whether people could be considered property.

Introduction

In 1677, the case of Butts v. Penny was heard by the court of King’s Bench, the highest Common Law court. The court’s decision was technically over just a few people, between 11 and 21 Africans, and over whether they could be sued over as though they were personal property or as a “good. ” The number is in question because the “10 and one half Negroes” mentioned in the case were counted using the Spanish measure of “Piezas” which counted a child or an ill or elderly person as half a person.

The plaintiff was Thomas Butts, a former Naval officer and employee of the Royal African Company (both institutions under the direction of James, Duke of York, King Charles II’s brother). The defendant, Penny, was a plantation owner in Barbados. Butts claimed that Penny had, by not paying a debt, illegally taken possession of his property: the 11-21 enslaved persons.

Penny’s lawyer, Thompson, argued that there could be no “Property in the Person of a Man sufficient to maintain Trover,” or that a person could not be sued over via a writ that applied to things. He argued that no one could have more power over such people under English law than that allowed under ancient feudal law, which tied people to land. People were not simple property to be recovered (or their value recovered) in such a way.

The four justices on the King’s Bench, presided over by Chief Justice Richard Rainsford, rejected Thompson’s argument, and decided in favor of the plaintiff, Thomas Butts. The court’s decision, reflected in the two court reports below, awarded him trover (the purported value of the 11-21 African men women and children) meaning that the court held that what we would now call a Tort (what they then called a “trespass”) could apply not only to things, but to people. This case, in which the King was directly involved, set the groundwork in the English Empire to treat enslaved persons as goods who be the subject of powerful writs. After two efforts to pass an imperial slave code via Parliament had failed, Charles II used the courts to bypass parliament.

The cases are somewhat vague but still very interesting. As you read these case reports, consider these questions: What rationale was used to define the enslaved persons as property? How might this decision correlate with the growth of slavery as an institution? The Royal African Company, whose Governor was James, Duke of York, brother to the king, had monopoly power over England’s slave trade. So, when it refers to “merchants,” who did they work for? Why not name them outright? Are there any logical limits in this decision?

Holly Brewer

Lauren Michalak

Further Reading

- Holly Brewer, “Creating a Common Law of Slavery for England and its New World Empire.” Law and History Review, 2021 39(4), 765-834. doi:10.1017/S0738248021000407

- Edward Fiddes, “Lord Mansfield and the Somersett Case” Law Quarterly Review 50 (1934): 499–511.

- F.O. Shylon, Black Slaves in Britain (London 1974).

- William M. Wiecek, “Somerest: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World,” University of Chicago Law Review 42 (1974): 86–146.

- David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Cornell UP: Ithaca, NY: 1975), esp.ch. 10.

- James Oldham, “New Light on Mansfield and Slavery” Journal of British Studies 27 (1988): 45–68.

- A. Leon Higginbotham, In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process I: The Colonial Period (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 323–27.

- George Van Cleve, “Somerset’s Case and Its Antecedents in Imperial Perspective,” Law and History Review 24 (2006): 601–46.

Sources

- Butts v. Penny, 83 Eng. Rep. 518, 519; Butts v. Penny, 84 Eng. Rep. 1011

- Transcription credit: Holly Brewer, Lauren Michalak, Hannah Nolan.

Cite this page

Content Warning

Please be aware that many of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions of punishment and enslavement that may be difficult to read. However, this language and these descriptions reveal the horrors of slavery. Please take care when transcribing these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

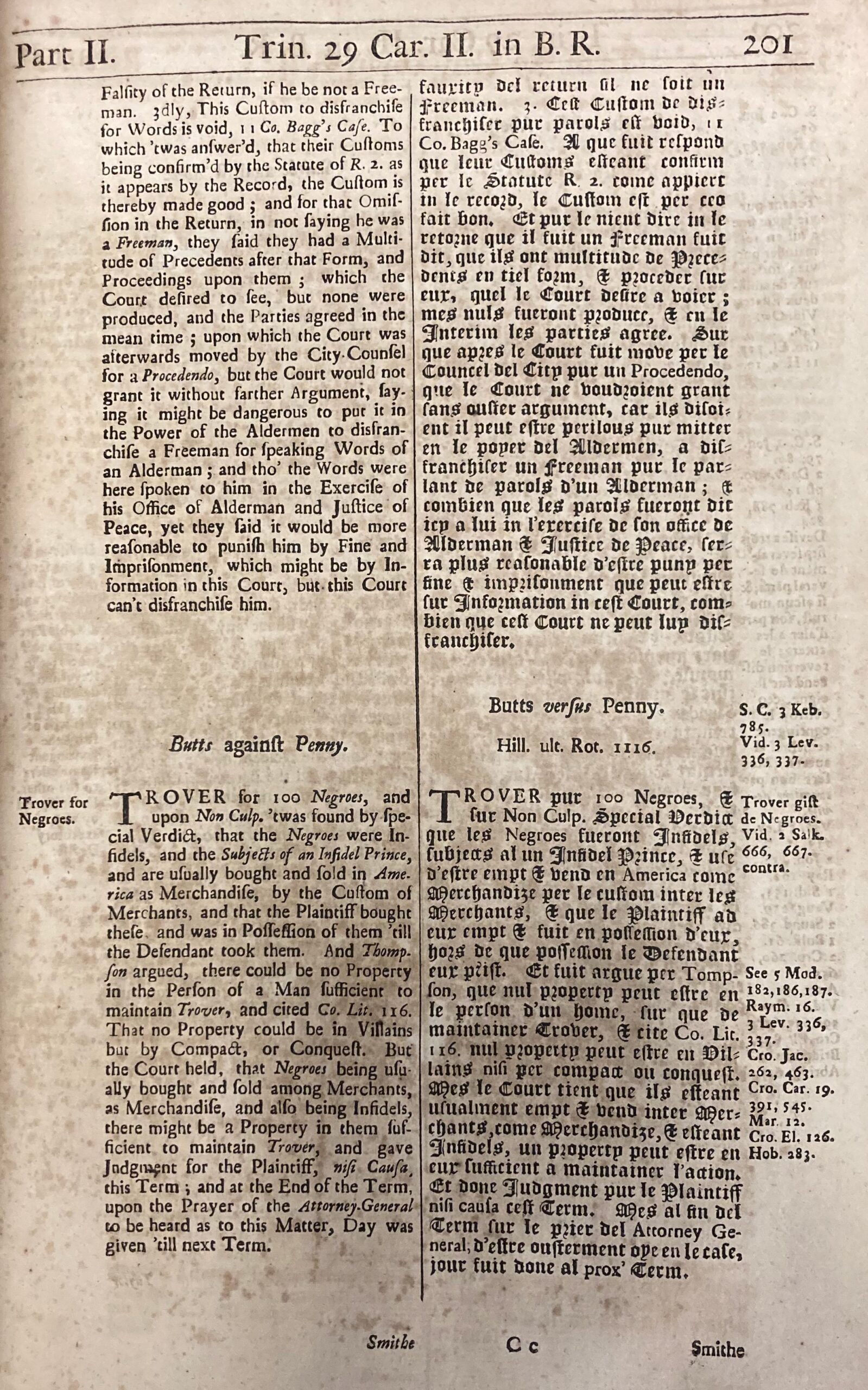

Butts against Penny, 2 LEV. 201. (83 Eng. Rep. 518, 519)

TRIN. 29 CAR. II. IN B. R.

TROVER for 100 Negroes, and upon Non Culp. ’twas found by special Verdict, that the Negroes were Infidels, and the Subjects of an Infidel Prince, and are usually bought and sold in America as Merchandise, by the Custom of Merchants, and that the Plaintiff bought these, and was in Possession of them until the Defendant took them. And Thompson argued, there could be no Property in the Person of a Man sufficient to maintain Trover, and cited Co. Lit. 116. That no Property could be in Villains but by Compact, or Conquest. But the Court held, that Negroes being usually bought and sold among Merchants, as Merchandise, and also being Infidels, there might be a Property in them sufficient to maintain Trover, and gave Judgment for the Plaintiff, nisi Causa, this Term; and at the End of the Term, upon the Prayer of the Attorney-General to be heard as to this Matter, Day was given ’till next Term.

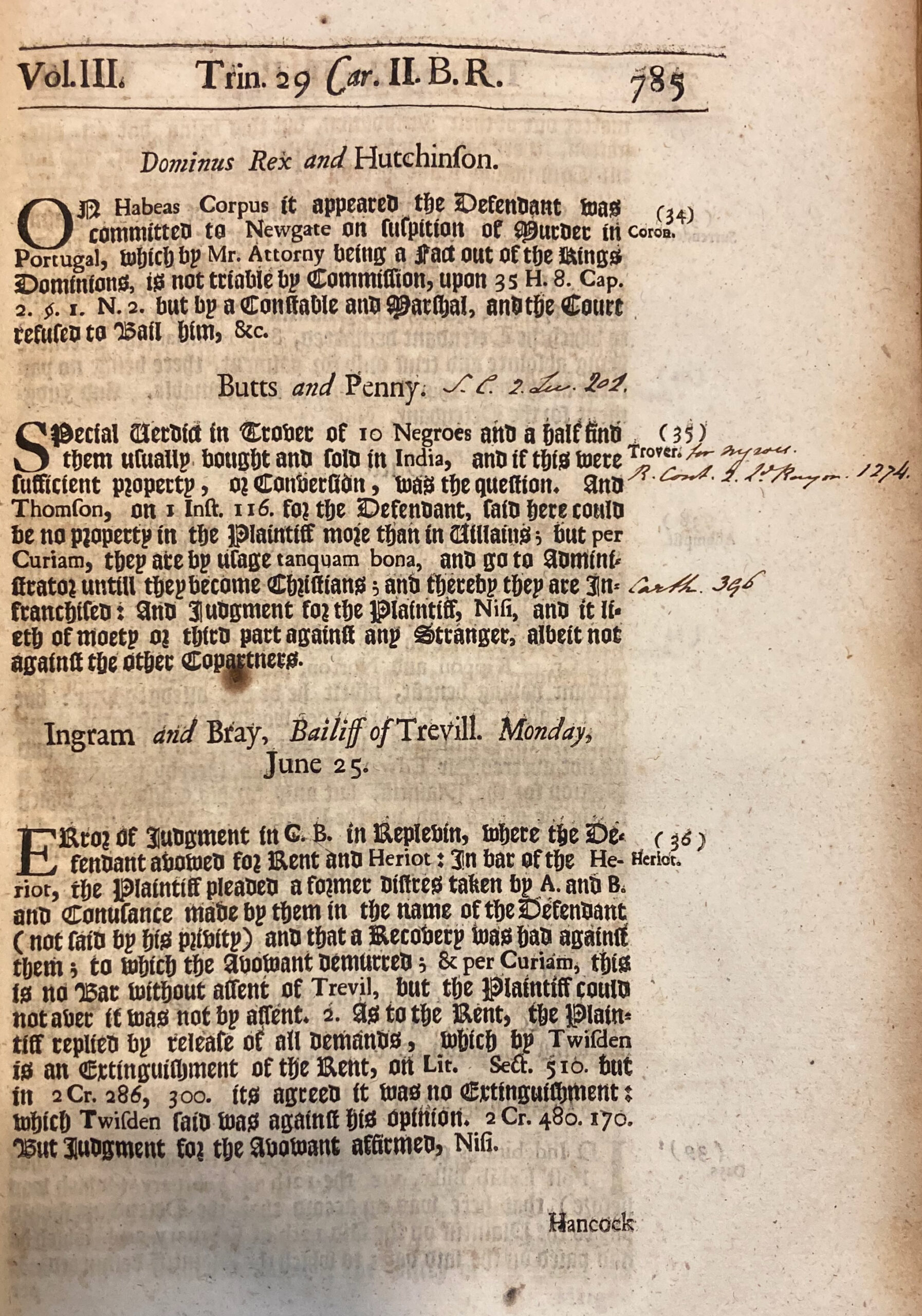

KEBLE, 785. TRIN. 29 CAR. II. B. R.

Butts and Penny.

Trover.

Special Verdict in Trover of 10 Negroes and a half find them usually bought and sold in India, and if this were sufficient property, or Conversion, was the question. And Thomson, on 1 Inst. 116, for the Defendant, said here could be no property in the plaintiff more than in Villains; but per Curiam, they are by usage tanquam bona, and go to Administrator untill they become Christians; and thereby they are Infranchised: and judgment for the Plaintiff, Nisi, and it lieth of moety or third part against any Stranger, albeit not against the other Copartners.

References

Collections

Tags

EARLY ACCESS: Transcription is under editorial review and may contain errors.

Please do not cite or otherwise reproduce without permission.

- Holly Brewer, “Creating a Common Law of Slavery for England and its New World Empire.” Law and History Review, 2021 39(4), 765-834. doi:10.1017/S0738248021000407

- Edward Fiddes, “Lord Mansfield and the Somersett Case” Law Quarterly Review 50 (1934): 499–511.

- F.O. Shylon, Black Slaves in Britain (London 1974).

- William M. Wiecek, “Somerest: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World,” University of Chicago Law Review 42 (1974): 86–146.

- David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Cornell UP: Ithaca, NY: 1975), esp.ch. 10.

- James Oldham, “New Light on Mansfield and Slavery” Journal of British Studies 27 (1988): 45–68.

- A. Leon Higginbotham, In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process I: The Colonial Period (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 323–27.

- George Van Cleve, “Somerset’s Case and Its Antecedents in Imperial Perspective,” Law and History Review 24 (2006): 601–46.

- Butts v. Penny, 83 Eng. Rep. 518, 519; Butts v. Penny, 84 Eng. Rep. 1011

- Transcription credit: Holly Brewer, Lauren Michalak, Hannah Nolan.