The Arraignment, Tryal & Condemnantion of Algernon Sidney – 3

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

[45]

believe have burned more Papers of my own writing than a Horse

can carry. So that for these Papers I can’t answer for them. There

is nothing in it, and what Concatenation can this have with the o-

ther design that is in it self nothing, with my Lords Select Counsel

selected by no body to pursue the design of my Lord Shaftsbury?

And this Counsel that he pretends to be set up for so great a business,

was to be adjusted with so much fineness so as to bring things toge-

ther, What was this fineness to do? (taking it for granted which I

don’t) This was nothing (if he was a credible Witness) but a few

Men talking at large of what might be or not be, what was like to

fall out without any manner of intention or doing any thing. They

did not so much as inquire. Whether there was Men in the Coun-

try, Arms, or Ammunition. A War to be made by five or six Men,

not knowing one another; not trusting one another. What said

Dr. Coxe in his evidence at my Lord Russel‘s Tryal, of my Lord Rus-

sel‘s trusting my Lord Howard? He might say the same of some others.

So that my Lord, I say, these Papers have no manner of coherence,

no dependance upon any such design. You must go upon conjecture

upon conjecture; and after all, you find nothing but only Papers, ne-

ver perfect, only scraps, written many years ago, and that could

not be calculated for the raising of the People. Now pray what

Imagination can be more vain than that? and what Man can be safe,

if the King’s Counsel may make such (whimsical I won’t say but)

groundless Constructions? Mr. Attorney says the Plot was broken

to the Scots (God knows we were neither broken nor joined) and

that the Cambells came to Town about that time I was taken, and in

the mean time my Lord Howard, the great Contriver of all this

Plot, who was most active; and advised the business that consisted

of so much fineness; he goes there and agrees of nothing: and then

goes into Essex upon great important business greater then the War

of England and Scotland, to what purpose? To look after a little

pimping Mannour, and what then? Why then it must be laid

aside, and he must be idle five Weeks at the Bath, and there is no in-

quiring after it. Now I desire your Lordship to consider, whether

there be a possibility for any Men, that have the sense of Porters and

Grooms; to do such things; as he would put upon us. I would only

say this, If Mr. Attorney be in the right there was a Combination

with the Scotts, and then this Paper was writ; for those that say I

did it, say, I was doing of it then, and by the Notes, there is work

enough for four or five years, to make out what is mentioned in

those scraps of Paper, and this must be to kill the King. And I say

this my Lord that under favour, for all constructive Treasons you

are to make none, but to go according to plain proof, and that

these Constructive Treasons belong only to Parliament, and by the

immediate Proviso in that Act. Now my Lord I leave it to your

Lordship, to see whether there is in this, any thing that you can say is

an Overt Act of Treason mentioned in 25 E. 3. If it be not plainly

[46]

under one of the two Branches, That I have endeavoured to kill the

King, or Levyed War, then ’tis matter of Construction, and that

belongs to no Court but the Parliament. Then my Lord this hath

been adjudged already in Throgmorton‘s Case. There is twenty Judg-

ments of Parliament, the Act of 13. Eliz. that says. – – I should

have somebody to speak for me my Lord.

L. C. Just. We are of another Opinion.

Mr. Just. Wythins. If you acknowledg the matter of Fact, you

say well.

Col. Sidney. I say there are several Judgments of Parliament, that

doe shew what ever is Constructive-Treason does not belong to

any private Court, that of 1 Mary. 1 E. 6. 1 Eliz. 5. Eliz. 18. ano-

ther 13 Car shew this. Now my Lord, I say that the business

concerning the Papers, ’tis only a similitude of hands, which is

just nothing. In my Lady Carrs Case, it was resolved to extend

to no criminal Cause, if not to any, then not to the greatest, the

most Capital. So that I have only this to say, That I think ’tis

impossible for the Jury to find this matter, for the first point you

proved by my Lord Howard that I think is no Body, and the last

concerning the Papers, is only imagination from the similitude of

hands. If I had published it, I must have answered for it, or if

the thing had been whole and mine, I must have answered for it;

but for these scraps never shewed any Body, That I think does

not at all concern me. And I say, if the Jury should find it

(which is impossible they can) I desire to have the Law reserved

unto me.

Mr. Sol. Gen. My Lord, and you Gentlemen of the Jury. The

Evidence hath been long; but I will endeavour to repeat it, as

faithfully as I can. The Crime the Prisoner stands accused for, is

compassing and imagining the Death of the King. That which we

go about to prove that compassing and imagining by, is by his

meeting and consulting how to raise Arms against the King, and

by plain matter in writing under his own hand, where he does

affirm, It is lawful to take away and destroy the King. Gentle-

men I will begin with the first part of it, the Meeting and Con-

sultation to raise Arms against the King. The Prisoner Gentle-

men hath endeavoured to avoid the whole force of this Evidence

by saying, that this in point of Law can’t affect him, if it were

all proved; for this does not amount to a proof of his compassing

and imagining the death of the King, and he is very long in in-

terpreting the Act of Parliament to you of 25 E. 3. and dividing

of it into several Members or Branches of Treason, And does in-

sist upon it, that tho’ this should be an offence within one Branch

of that Statute, yet that is not a proof of the other, which is the

Branch he is proceeded upon, that is the first Clause against the

compassing and imagining the Death of the King. And, sais he,

[47]

conspiring to Levy War is not so much as one Branch of that Sta-

tute, but it must be War actually levyed. This is a matter he is

wholly mistaken in, in point of Law. It hath been adjudged over and

over again, That an Act which in one Branch of that Statute may

be an overt Act to prove a man Guilty of another Branch of it. As

levying War is an overt Act to prove a man Guilty of Conspiring

the Death of the King. And this was adjudged in the Case of

Sir Henry Vane, so is meeting and consulting to raise to Arms. And

reason does plainly speak it to be so; for they that conspire to

raise War against the King, can’t be presumed to stop any where;

till they have Dethron’d or Murdered the King. Gentlemen I

won’t belong in citing Authoritys, It hath been setled lately by

all the Judges of England, in the Case of my Lord Russel, who hath

suffered for this Conspiracy. Therefore that point of Law will

be very plain against the Prisoner. He hath mentioned some other

things, as that there must be two Witnesses to every particular

Fact, and one Witness to one Fact, and another to another is not

sufficient, it hath been very often objected, and as often over-ru-

led: It was over-ruled Solemnly in the Case of my Lord Stafford.

Therefore if we have one Witness to one overt Act, and another

to another, they will be two Witnesses in Law to convict this Pri-

soner. In the first part of our Evidence, we give you an account

of the general Design of an Insurrection that was to have been,

that this was contrived first, when my Lord Shaftsbury was in

England, that after my Lord Shaftsbury was gone, the business did

not fall; but they thought fit to revive it again, and that they

might carry it on the more steadily, they did contrive a Coun-

sel among themselves of six, whereof the Prisoner at the Bar was

one. They were the Duke of Monmouth, my Lord of Essex, my

Lord Howard, my Lord Russel, the Prisoner at the Bar, and Mr.

Hambden. This Counsel they contrived to manage this affair,

and to carry on that designe, that seemed to fall by the Death of

my Lord of Shaftsbury, and they met; this we give you an account

of, first by Witnesses that gave you an account in general of it.

And tho’ they were not privy to it, yet they heard of this Coun-

sel, and that Col. Sidney was to be one of this Counsel. This

Gentlemen, If it had stood alone by it self, had been nothing to

affect the Prisoner at all. But this will shew you, that this was

discours’d among them that were in this Conspiracy. Then my

Lord Howard gives you an account that first the Duke of Mon-

mouth, and he, and Col. Sidney met, and it was agreed to be ne-

cessary to have a Counsel that should consist of six or seven,

and they were to carry it on. That the Duke of Monmouth under-

took to dispose my Lord Russel to it, and Col. Sidney to dispose

the Earl of Essex, and Mr. Hambden: that these Gentlemen

did meet accordingly, and the substance of their discourse was,

taking notice how the design had fallen upon the Death of my

[48]

Lord Shaftsbury, that it was fit to carry it on before mens

Inclinations were cool, for they found they were ready to it,

and had great reason to believe it, because this being a bu-

siness communicated to so many, yet for all that it was kept

very secret, and no body had made any mention of it, which

they looked upon a certaine argument that men were ready to

ingage in it. This incouraged them to go on in this Conspiracy.

Then when the Six met at Mr. Hambden‘s house, they debated con-

cerning the place of rising, and the time, the time they conceiv’d

must be suddenly before Mens minds were cool, for now they thought

they were ready and very much disposed to it, and for place, they

had in debate whether they should rise first in the Town, or in the

Country, or both together. And for the Persons they thought it

absolutely necessary for them to have the United Counsels of Scot-

land to join with them, and therefore they did refer this matter to

be better considered of another time, and they met afterwards at

my Lord Russel‘s House in February, and there they had Discourse

to the same purpose. But there they began to consider with them-

selves, being they were to destroy this Government, what they

should set up in the room of it; to what purpose they ingaged. TFor

they did very wisely consider, If this be only to serve a turn, and to

make one Man great, this will be a great hinderance in their Af-

fair, therefore they thought it was necessary to ingage upon a pub-

lick account, and to resolve all into the authority of a Parliament,

which surely they either thought to force the King to call, or other-

wise, that the People might call a Parliament, if the King refused, and

so they to choose their own Heads. But still they were upon this

point, That it was necessary for their Friends in Scotland to have

their Counsels united with them, and in order to that, it was neces-

sary to contrive some way to send a Messenger into Scotland, to

bring some Men here to treat and consult about it, and Col. Sidney

is the Man that does engage to send this Messenger, and he had a

man very fit for his turn, that is, Aaron Smith, whom he could con-

fide in, and him he undertook to send into Scotland. This Mes-

senger was to fetch my Lord Melvin, the two Cambells, and

Sir John Cockram, Col. Sidney as he ingaged to do this, so after-

wards he did shew to my Lord Howard Money, which he af-

firmed was for that business, he says it was a Sum of about sixty

Guinneys, and he believes he gave it him, for that Col. Sidney

told him, Aaron Smith was gone into Scotland, That the Pretence

was not bare-faced to invite them over to consult of a Rebellion,

but to consult about the business of Carolina, being a Plantation

for the Persecuted Brethren, as they pretended in Scotland. Gen-

tlemen, these Scotch-men that were thus sent for over, they came

accordingly, that is, the two Cambells, and Sir John Cockram, and the

Discourse with Sir Andrew Foster was according to this Cant that

was agreed on beforehand, concerning a Plantation in Carolina.

[49]

This was that that was pretended for their coming hither; but the

true Errand was, the business of the Insurrection intended. Gentle-

men, that they came upon such a design, is evident from the circum-

stances; they came about the time the business brake out, and in

that time suspiciously changing their Lodging, they were taken ma-

king their escape, and this at a time before it was probable to be

known abroad, that these men were named as part of the Conspira-

tors. These things do very much verifie the Evidence my Lord

Howard hath given, and there is nothing has been said does at all

invalidate it. The sending of Aaron Smith into Scotland, and his

going, and the coming of these men, and their endeavouring to make

their escape, are mighty concurrent Evidences with the whole Evi-

dence my Lord Howard has given. Now, What objections are

made against this Evidence? truly none at all. Here are persons

of great Quality have given their Testimony, and they do not im-

peach my Lord Howard in the least; but some do extremely confirm

the truth of my Lord Howard. My Lord Anglesey gives you an ac-

count of a discourse at my Lord of Bedfords, That my Lord Howard

came in, and that my Lord Howard should there comfort my Lord

of Bedford, and enlarge in the Commendations of his Son, and say

he was confident he knew nothing of the Design, and he must be

innocent. Gentlemen, This is the nature of the most part of the

Evidence. My Lord of Clare his Evidence is much the like, that is,

his denying that he knew of any Plot. Now here is my Lord

Howard under a guilt of High-Treason; for he was one of those

Conspirators not yet discovered, nor no Evidence of any discourse

leading to any thing that should give occasion to him to protest his

innocency: and, says he, I know nothing of the Plot. You would

have wondered if he should have been talking in all places his know

ledg, and declaring himself: His denying of it under the guilt, when

he was not accused, is nothing to his Confession when he comes to be

apprehended and taken for it. Here Mr. Philip Howard says, he

had several discourses with him about this business upon the break-

ing out of the Plot, and that he advised him to make an Address,

and that this was a thing that would be very acceptable, and very

much for their vindication; and my Lord Howard (he says) thanked

him for his very good advice, and said, he would follow it: and

presently after when my Lord Russel was apprehended;

this was sudden to him. And what says he? We are all un-

done. When my Lord Russel that was one of this Counsel that

was a secret Counsel, and could not be traced but by some of

themselves, when he is apprehended, then he falls out into this ex-

pression, We are all undone. This is an Argument my Lord

Howard had a guilt upon him. For, why were they all undone,

that my Lord Russel was apprehended, any more than upon the

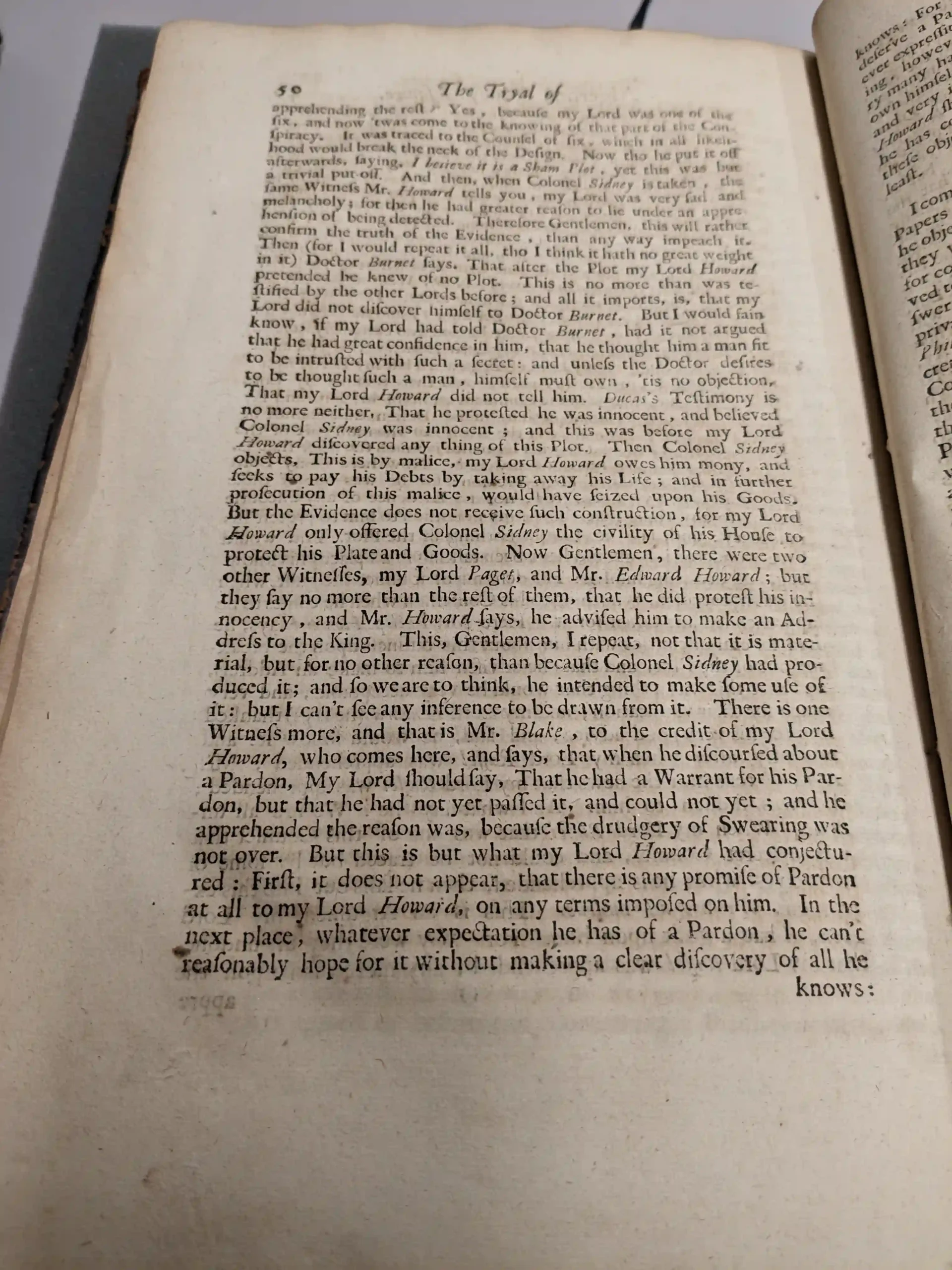

[50]

apprehending the rest? Yes, because my Lord was one of the

six, and now ’twas come to the knowing of that part of the Con-

spiracy. It was traced to the Counsel of six, which in all likeli-

hood would break the neck of the Design. Now tho he put it off

afterwards, saying, I believe it is a Sham Plot, yet this was but

a trivial put-off. And then, when Colonel Sidney is taken, the

same Witness Mr. Howard tells you, my Lord was very sad and

melancholy; for then he had greater reason to lie under an appre-

hension of being detected. Therefore Gentlemen, this will rather

confirm the truth of the Evidence, than any way impeach it.

Then (for I would repeat it all, tho I think it hath no great weight

in it) Doctor Burnet says, That after the Plot my Lord Howard

pretended he knew of no Plot. This is no more than was te-

stified by the other Lords before; and all it imports, is, that my

Lord did not discover himself to Doctor Burnet. But I would fain

know, if my Lord had told Doctor Burnet, had it not argued

that he had great confidence in him, that he thought him a man fit

to be intrusted with such a secret; and unless the Doctor desires

to be thought such a man, himself must own, ’tis no objection,

That my Lord Howard did not tell him. Ducas‘s Testimony is

no more neither, That he protested he was innocent, and believed

Colonel Sidney was innocent; and this was before my Lord

Howard discovered any thing of this Plot. Then Colonel Sidney

objects, This is by malice, my Lord Howard owes him mony, and

seeks to pay his Debts by taking away his Life; and in further

prosecution of this malice, would have seized upon his Goods.

But the Evidence does not receive such construction, for my Lord

Howard only offered Colonel Sidney the civility of his House to

protect his Plate and Goods. Now Gentlemen, there were two

other Witnesses, my Lord Paget, and Mr. Edward Howard; but

they say no more than the rest of them, that he did protest his in-

nocency, and Mr. Howard says, he advised him to make an Ad-

dress to the King. This, Gentlemen, I repeat, not that it is mate-

rial, but for no other reason, than because Colonel Sidney had pro-

duced it; and so we are to think, he intended to make some use of

it: but I can’t see any inference to be drawn from it. There is one

Witness more, and that is Mr. Blake, to the credit of my Lord

Howard, who comes here, and says, that when he discoursed about

a Pardon, My Lord should say, That he had a Warrant for his Par-

don, but that he had not yet passed it, and could not yet; and he

apprehended the reason was, because the drudgery of Swearing was

not over. But this is but what my Lord Howard had conjectu-

red: First, it does not appear, that there is any promise of Pardon

at all to my Lord Howard, on any terms imposed on him. In the

next place, whatever expectation he has of a Pardon, he can’t

reasonably hope for it without making a clear discovery of all he

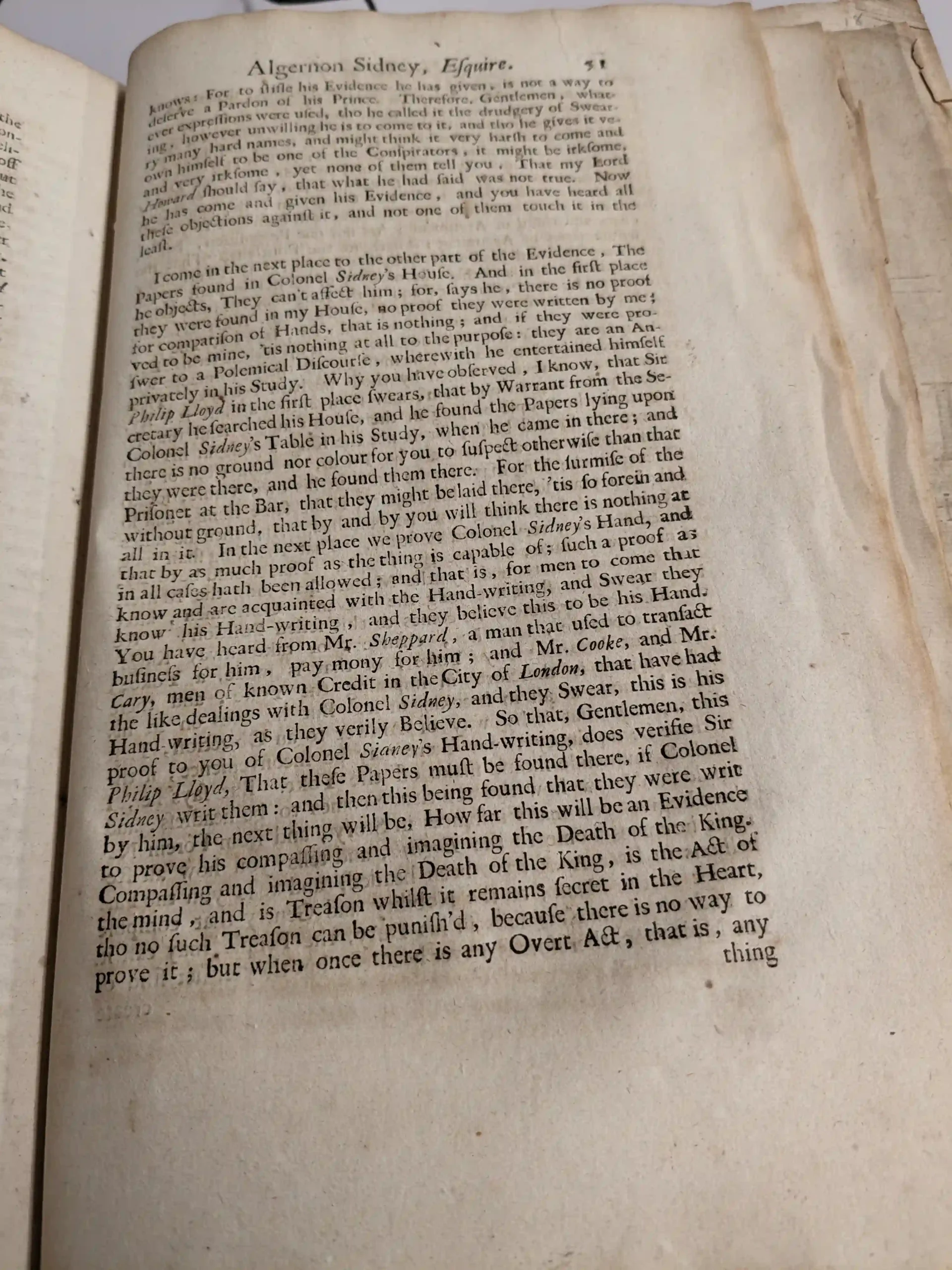

[51]

knows: For to stifle his Evidence he has given, is not a way to

deserve a Pardon of his Prince. Therefore, Gentlemen, what-

ever expressions were used, tho he called it the drudgery of Swear-

ing, however unwilling he is to come to it, and tho he gives it ve-

ry many hard names, and might think it very harsh to come and

own himself to be one of the Conspirators, it might be irksome,

and very irksome, yet none of them tell you, That my Lord

Howard should say, that what he had said was not true. Now

he has come and given his Evidence, and you have heard all

these objections against it, and not one of them touch it in the

least.

I come in the next place to the other part of the Evidence, The

Papers found in Colonel Sidney‘s House. And in the first place

he objects, They can’t affect him; for, says he, there is no proof

they were found in my House, no proof they were written by me;

for comparison of Hands, that is nothing; and if they were pro-

ved to be mine, ’tis nothing at all to the purpose: they are an An-

swer to a Polemical Discourse, wherewith he entertained himself

privately in his Study. Why you have observed, I know, that Sir

Philip Lloyd in the first place swears, that by Warrant from the Se-

cretary he searched his House, and he found the Papers lying upon

Colonel Sidney‘s Table in his Study, when he came in there; and

there is no ground nor colour for you to suspect otherwise than that

they were there, and he found them there. For the surmise of the

Prisoner at the Bar, that they might be laid there, ’tis so forein and

without ground, that by and by you will think there is nothing at

all in it. In the next place we prove Colonel Sidney‘s Hand, and

that by as much proof as the thing is capable of; such a proof as

in all cases hath been allowed; and that is, for men to come that

know and are acquainted with the Hand-writing, and Swear they

know his Hand-writing, and they believe this to be his Hand.

You have heard from Mr. Sheppard, a man that used to transact

business for him, pay mony for him; and Mr. Cooke, and Mr.

Cary, men of known Credit in the City of London, that have had

the like dealings with Colonel Sidney, and they Swear, this is his

Hand-writing, as they verily Believe. So that, Gentlemen, this

proof to you of Colonel Sidney‘s Hand-writing, does verifie Sir

Philip Lloyd, That these Papers must be found there, if Colonel

Sidney writ them: and then this being found that they were writ

by him, the next thing will be, How far this will be an Evidence

to prove his compassing and imagining the Death of the King.

Compassing and imagining the Death of the King, is the Act of

the mind, and is Treason whilst it remains secret in the Heart,

tho no such Treason can be punish’d, because there is no way to

prove it; but when once there is any Overt Act, that is, any

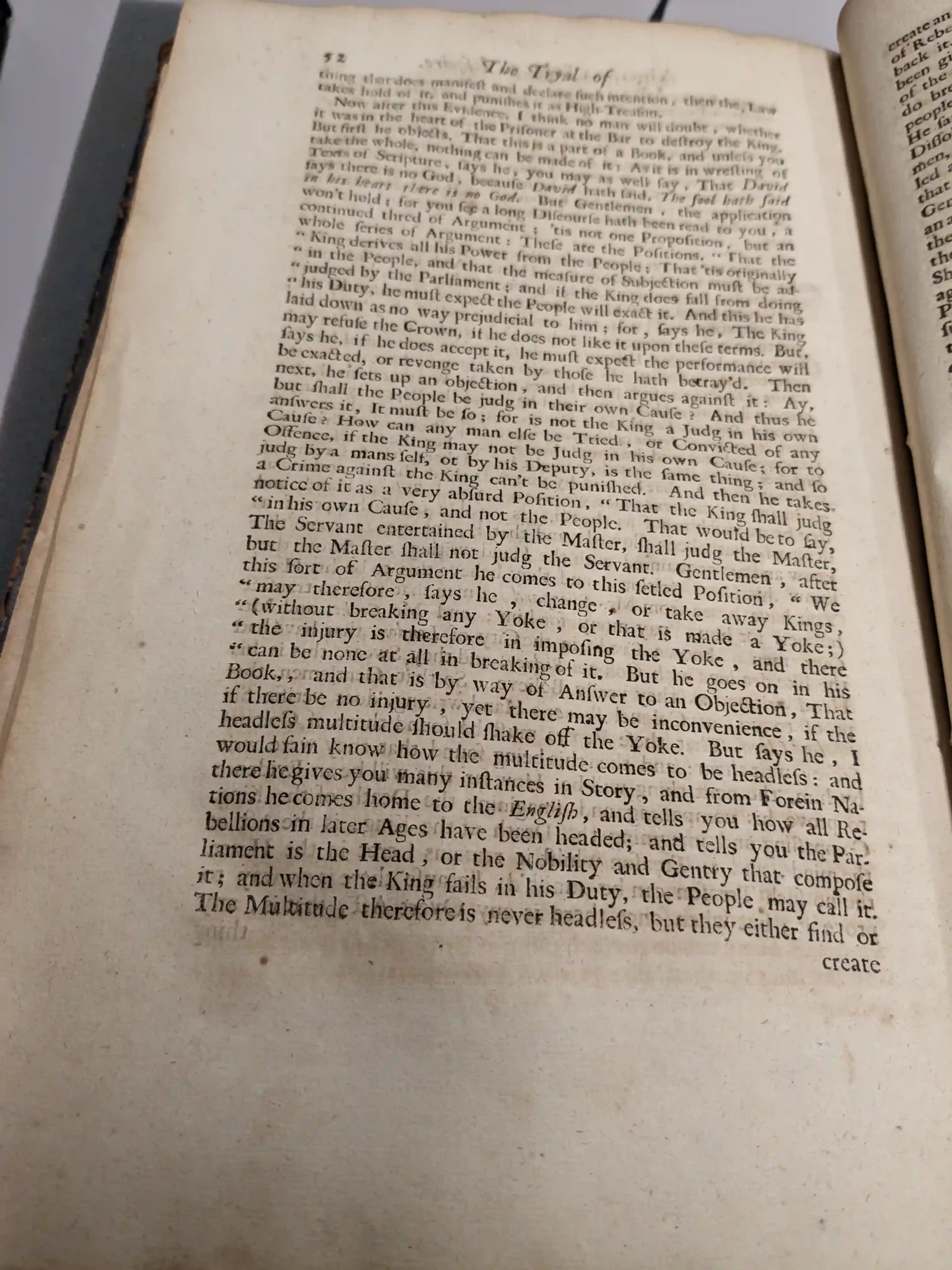

[52]

thing that does manifest and declare such intention, then the Law

takes hold of it, and punishes it as High Treason.

Now after this Evidence, I think no man will doubt, whether

it was in the heart of the Prisoner at the Bar to destroy the King.

But first he objects, That this is a part of a Book, and unless you

take the whole, nothing can be made of it: As it is in wresting of

Texts of Scripture, says he, you may as well say, That David

says there is no God, because David hath said, The fool hath said

in his heart there is no God. But Gentlemen, the application

won’t hold; for you see a long Discourse hath been read to you, a

continued thred of Argument; ’tis not one Proposition, but an

whole series of Argument: These are the Positions, “That the

” King derives all his Power from the People; That ’tis originally

” in the People, and that the measure of Subjection must be ad-

” judged by the Parliament; and if the King does fall from doing

” his Duty, he must expect the People will exact it. And this he has

laid down as no way prejudical to him; for, says he, The King

may refuse the Crown, if he does not like it upon these terms. But,

says he, if he does accept it, he must expect the performance will

be exacted, or revenge taken by those he hath betray’d. Then

next, he sets up an objection, and then argues against it: Ay,

but shall the People be judg in their own Cause? And thus he

answers it, It must be so; for is not the King a Judg in his own

Cause? How can any man else be Tried, or Convicted of any

Offence, if the King may not be Judg in his own Cause; for to

judg by a mans self, or by his Deputy, is the same thing; and so

a Crime against the King can’t be punished. And then he takes

notice of it as a very absurd Position, “That the King shall judg

” in his own Cause, and not the People. That would be to say,

The Servant entertained by the Master, shall judg the Master,

but the Master shall not judg the Servant. Gentlemen, after

this sort of Argument he comes to this setled Position, “We

” may therefore, says he, change, or take away Kings,

” (without breaking any Yoke, or that is made a Yoke;)

” the injury is therefore in imposing the Yoke, and there

” can be none at all in breaking of it. But he goes on in his

Book, , and that is by way of Answer to an Objection, That

if there be no injury, yet there may be inconvenience, if the

headless multitude should shake off the Yoke. But says he, I

would fain know how the multitude comes to be headless; and

there he gives you many instances in Story, and from Forein Na-

tions he comes home to the English, and tells you how all Re-

bellions in later Ages have been headed; and tells you the Par-

liament is the Head, or the Nobility and Gentry that compose

it; and when the King fails in his Duty, the People may call it.

The Multitude therefore is never headless, but they either find or

[53]

create an head, so that here is a plain and an avowed Principle

of Rebellion Established upon the strongest reason he has to

back it. Gentlemen, This with the other Evidence that has

been given, will be sufficient to prove his Compassing the Death

of the King. You see the Affirmations he makes: when Kings

do break their Trust they may be called to accompt by the

people. This is the Doctrine he Broaches and Argues for:

He says in his Book in another part, that the Calling and

Dissolving of Parliaments is not in the Kings Power. Gentle-

men, You all know how many Parliaments the King hath Cal-

led and Dissolved; if it be not in his Power, he hath done that

that was not in his Power, and so contrary to his Trust.

Gentlemen, at the entrance into this Conspiracy they were under

an apprehension that their Liberties were invaded, as you hear in

the Evidence from my Lord Howard, that they were just making

the Insurrection upon that Tumultuous opposition of Electing of

Sheriffs in London. They enter into a Consultation to raise Arms

against the King; and it is proved by my Lord Howard, that the

Prisoner at the Bar was one. Gentlemen, Words spoken upon a

supposition will be High-Treason, as was held in King James‘s

time, in the Case of Collins in Rolls Reports, The King being Ex-

communicate may be Deposed and Murdered, without affirming he

was Excommunicated; and this was enough to Convict him of

High Treason. Now according to that Case, to say the King

having broken his Trust may be Deposed by his people, would be

High Treason, but here he does as good as affirm the King had

broke his Trust. When every one sees the King hath Dissolved

Parliaments; this reduces it to an Affirmation. And though this

Book be not brought to that Counsel to be perused, and there

debated, yet it will be another, and more than two Witnesses

against the Prisoner: For I would ask any man, suppose a man was

in a Room, and there were two men, and talks with both a-

part, and he comes to one and endeavours to persuade him that it is

lawful to Rise in Arms against the King, if so be he break his

Trust, and he should go to another man, and tell him the King

hath broken his Trust, and we must seek some way to redress our

selves, and persuade the people to Rise; these two Witnesses do

so tack this Treason together, that they will be two Witnesses to

prove him Guilty of High Treason. And you have heard one

Witness prove it positively to you, That he consulted to Rise in

Arms against the King, and here is his own Book says, it is lawful

for a man to Rise in Arms against the King, if he break his Trust,

and in effect he hath said, the King hath broken his Trust: There-

fore this will be a sufficient demonstration what the imagination of

the Heart of this man was, that it was nothing but the destru-

ction of the King and the Government, and indeed of all Go-

vernments. There can be no such thing as Government if the people

shall be Judg in the Case: For what so uncertain as the heady

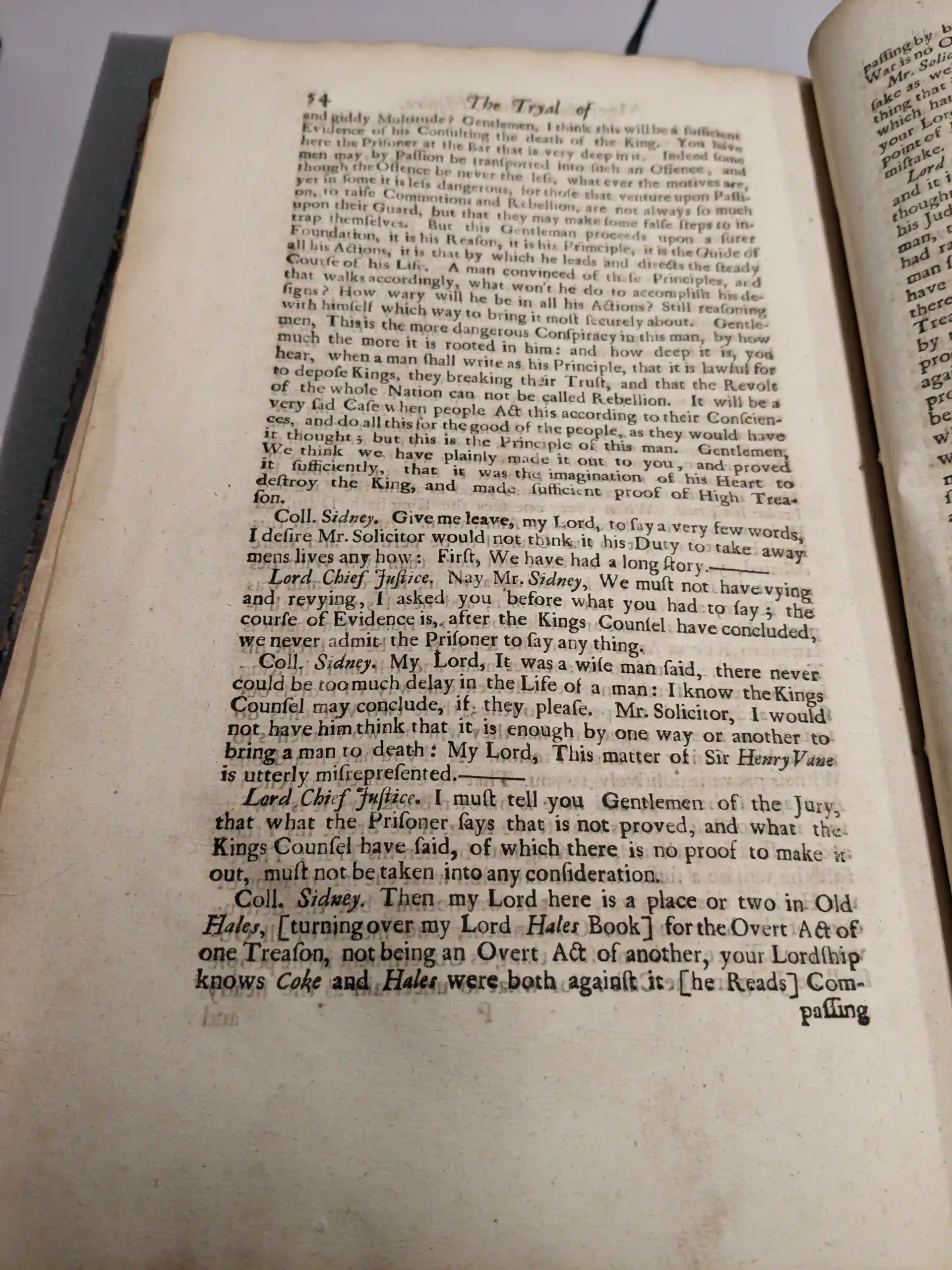

[54]

and giddy Multitude? Gentlemen, I think this will be a sufficient

Evidence of his Consulting the death of the King. You have

here the Prisoner at the Bar that is very deep in it. Indeed some

men may by Passion be transported into such an Offence, and

though the Offence be never the less, what ever the motives are,

yet in some it is less dangerous, for those that venture upon Passi-

on, to raise Commotions and Rebellion, are not always so much

upon their Guard, but that they may make some false steps to in-

trap themselves. But this Gentleman proceeds upon a surer

Foundation, it is his reason, it is his Principle, it is the Guide of

all his Actions, it is that by which he leads and directs the steady

Course of his Life. A man convinced of these Principles, and

that walks accordingly, what won’t he do to accomplish his de-

signs? How wary will he be in all his Actions? Still reasoning

with himself which way to bring it most securely about. Gentle-

men, This is the more dangerous Conspiracy in this man, by how

much the more it is rooted in him: and how deep it is, you

hear, when a man shall write as his Principle, that it is lawful for

to depose Kings, they breaking their Trust, and that the Revolt

of the whole Nation can not be called Rebellion. It will be a

very sad Case when people Act this according to their Conscien-

ces, and do all this for the good of the people, as they would have

it thought; but this is the Principle of this man. Gentlemen,

We think we have plainly made it out to you, and proved

it sufficiently, that it was the imagination of his Heart to

destroy the King, and made sufficient proof of High Trea-

son.

Coll. Sidney, Give me leave, my Lord, to say a very few words,

I desire Mr. Solicitor would not think it his Duty to take away

mens lives any how: First, We have had a long story. —-

Lord Chief Justice. Nay Mr. Sidney, We must not have vying

and revying, I asked you before what you had to say; the

course of Evidence is, after the Kings Counsel have concluded,

we never admit the Prisoner to say any thing.

Coll. Sidney. My Lord, It was a wise man said, there never

could be too much delay in the Life of a man: I know the Kings

Counsel may conclude, if they please. Mr. Solicitor, I would

not have him think that it is enough by one way or another to

bring a man to death: My Lord, This matter of Sir Henry Vane

is utterly misrepresented. —-

Lord Chief Justice. I must tell you Gentlemen of the Jury,

that what the Prisoner says that is not proved, and what the

Kings Counsel have said, of which there is no proof to make it

out, must not be taken into any consideration.

Coll. Sidney. Then my Lord here is a place or two in Old

Hales, [turning over my Lord Hales Book] for the Overt Act of

one Treason, not being an Overt Act of another, your Lordship

knows Coke and Hales were both against it [he Reads] Com-

[55]

passing by bare words is not an Overt Act, Conspiring to Levy

War is no Overt Act.

Mr. Solicitor General. I desire but one word more for my own

sake as well as the Prisoners, and that is, that if I have said any

thing that is not Law, or misrepeated, or misapplied the Evidence

which hath been given, I do make it my humble Request to

your Lordship to rectifie those mistakes as well in point of Fact as

point of Law; for God forbid the Prisoner should suffer by any

mistake.

Lord Chief Justice. Gentlemen, The Evidence has been long,

and it is a Cause of great concernment, and it is far from the

thoughts of the King, or from the thoughts or desire of any of

his Judges here to be instrumental to take away the life of any

man, that by Law his Life ought not to be taken away. For I

had rather many Guilty men should escape, than one innocent

man suffer. The question is, whether upon all the Evidence you

have heard against the Prisoner, and the Evidence on his behalf,

there is Evidence sufficient to Convict the Prisoner of the High

Treason he stands charged with. And as you must not be moved

by the denyal of the Prisoner further than as it is backed with

proof, so you are not to be inveigled by any insinuations made

against the Prisoner at the Bar, further or otherwise than as the

proof is made out to you. But it is usual, and it is a duty incum-

bent on the King’s Counsel to urge against all such Criminals,

whatsoever they observe in the Evidence against them, and like-

wise to endeavour to give answers to the Objections that are

made on their behalf. And therefore, since we have been kept

so long in this Cause, it won’t be amiss for me (and my Brothers,

as they shall think fit, ) to help your memory in the fact, and

discharge that Duty that is incumbent upon the Court as to the

points of Law. This Indictment is for High Treason, and is

grounded upon the Statute of 25 E. 3. By which Statute the com-

passing and imagining the death of the King, and declaring the

same by an Overt Act is made High Treason. The reason of that

Law was, because at Common Law there was great doubt what

was Treason; wherefore to reduce that High Crime to a certain-

ty, was that Law made, that those that were Guilty might know

what to expect. And there are several Acts of Parliament made

between the time of Edward the Third, and that of 1 M. but

by that Statute all Treasons that are not enumerated by after

Acts of Parliament remain as they were declared by that Statute

of 25 E. 3. And so are Challenges and other matters insisted upon

by the Prisoner, left as they were at the time of that Act: I am

also to tell you that in point of Law, it is not only the Opinion of

us here, but the Opinion of them that sate before us, and the Opi-

nion of all the Judges of England, and within the memory of

many of you,

[56]

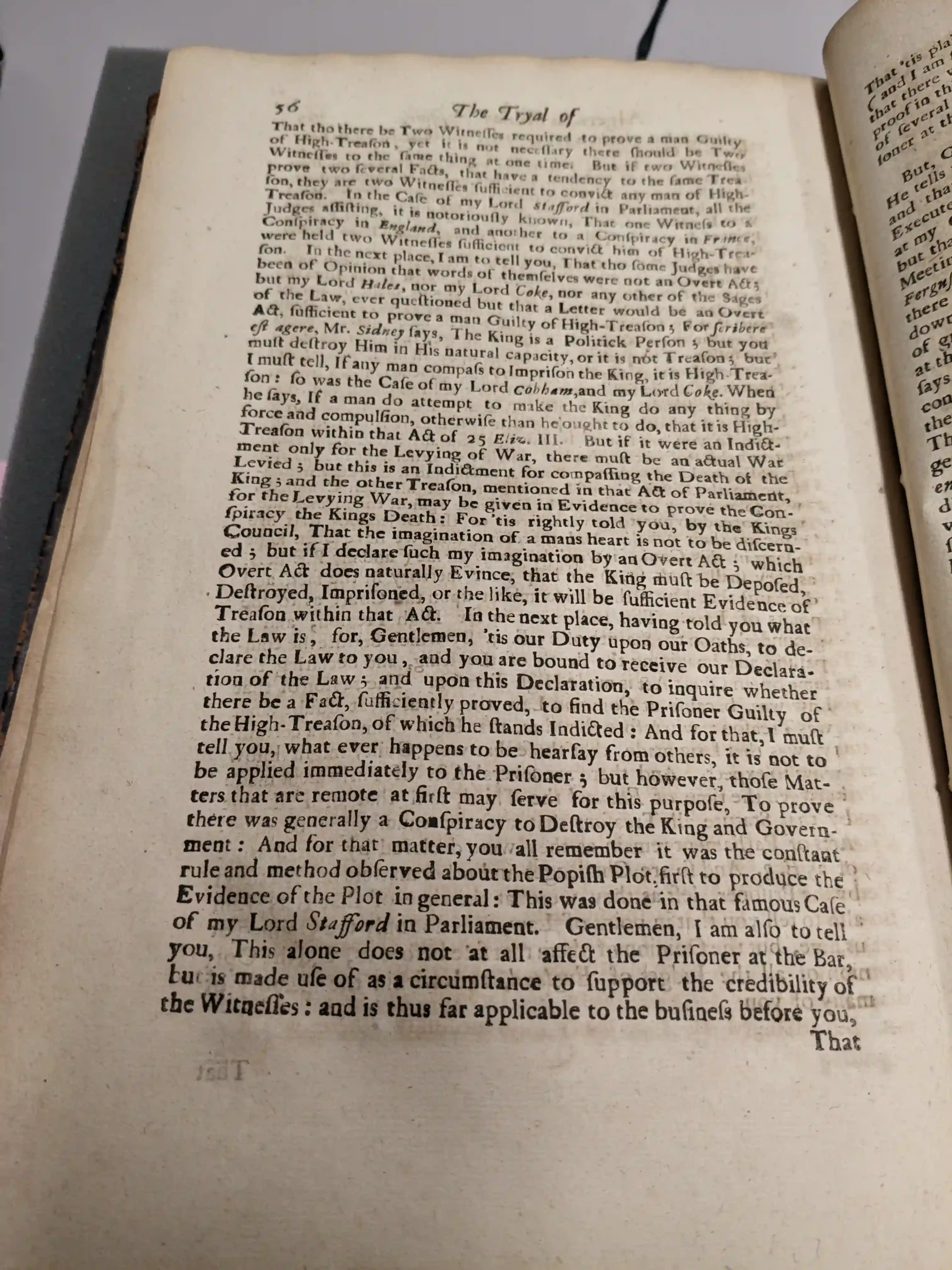

That tho there be Two Witnesses required to prove a man Guilty

of High-Treason, yet it is not necessary there should be Two

Witnesses to the same thing at one time. But if two Witnesses

prove two several Facts, that have a tendency to the same Trea-

son, they are two Witnesses sufficient to convict any man of High-

Treason. In the Case of my Lord Stafford in Parliament, all the

Judges assisting, it is notoriously known, That one Witness to a

Conspiracy in England, and another to a Conspiracy in France,

were held two Witnesses sufficient to convict him of High-Trea-

son. In the next place, I am to tell you, That tho some Judges have

been of Opinion that words of themselves were not an Overt Act;

but my Lord Hales, nor my Lord Coke, nor any other of the Sages

of the Law, ever questioned but that a Letter would be an Overt

Act, sufficient to prove a man Guilty of High-Treason; For scribere

est agere, Mr. Sidney says, The King is a Politick Person; but you

must destroy Him in His natural capacity, or it is not Treason; but

I must tell, If any man compass to Imprison the King, it is High Trea-

son: so was the Case of my Lord Cobham, and my Lord Coke. When

he says, If a man do attempt to make the King do any thing by

force and compulsion, otherwise than he ought to do, that it is High-

Treason within that Act of 25 Eliz. III. But if it were an Indict-

ment only for the Levying of War, there must be an actual War

Levied; but this is an Indictment for compassing the Death of the

King; and the other Treason, mentioned in that Act of Parliament,

for the Levying War, may be given in Evidence to prove the Con-

spiracy the Kings Death: For ’tis rightly told you, by the Kings

Council, That the imagination of a mans heart is not to be discern-

ed; but if I declare such my imagination by an Overt Act; which

Overt Act does naturally Evince, that the King must be Deposed,

Destroyed, Imprisoned, or the like, it will be sufficient Evidence of

Treason within that Act. In the next place, having told you what

the Law is, for, Gentlemen, ’tis our Duty upon our Oaths, to de-

clare the Law to you, and you are bound to receive our Declara-

tion of the Law; and upon this Declaration, to inquire whether

there be a Fact, sufficiently proved, to find the Prisoner Guilty of

the High-Treason, of which he stands Indicted: And for that, I must

tell you, what ever happens to be hearsay from others, it is not to

be applied immediately to the Prisoner; but, however, those Mat-

ters that are remote at first may serve for this purpose, To prove

there was generally a Conspiracy to Destroy the King and Govern-

ment: And for that matter, you all remember it was the constant

rule and method observed about the Popish Plot, first to produce the

Evidence of the Plot in general: This was done in that famous Case

of my Lord Stafford in Parliament. Gentlemen, I am also to tell

you, This alone does not at all affect the Prisoner at the Bar,

but is made use of as a circumstance to support the credibility of

the Witnesses: and is thus far applicable to the business before you,

[57]

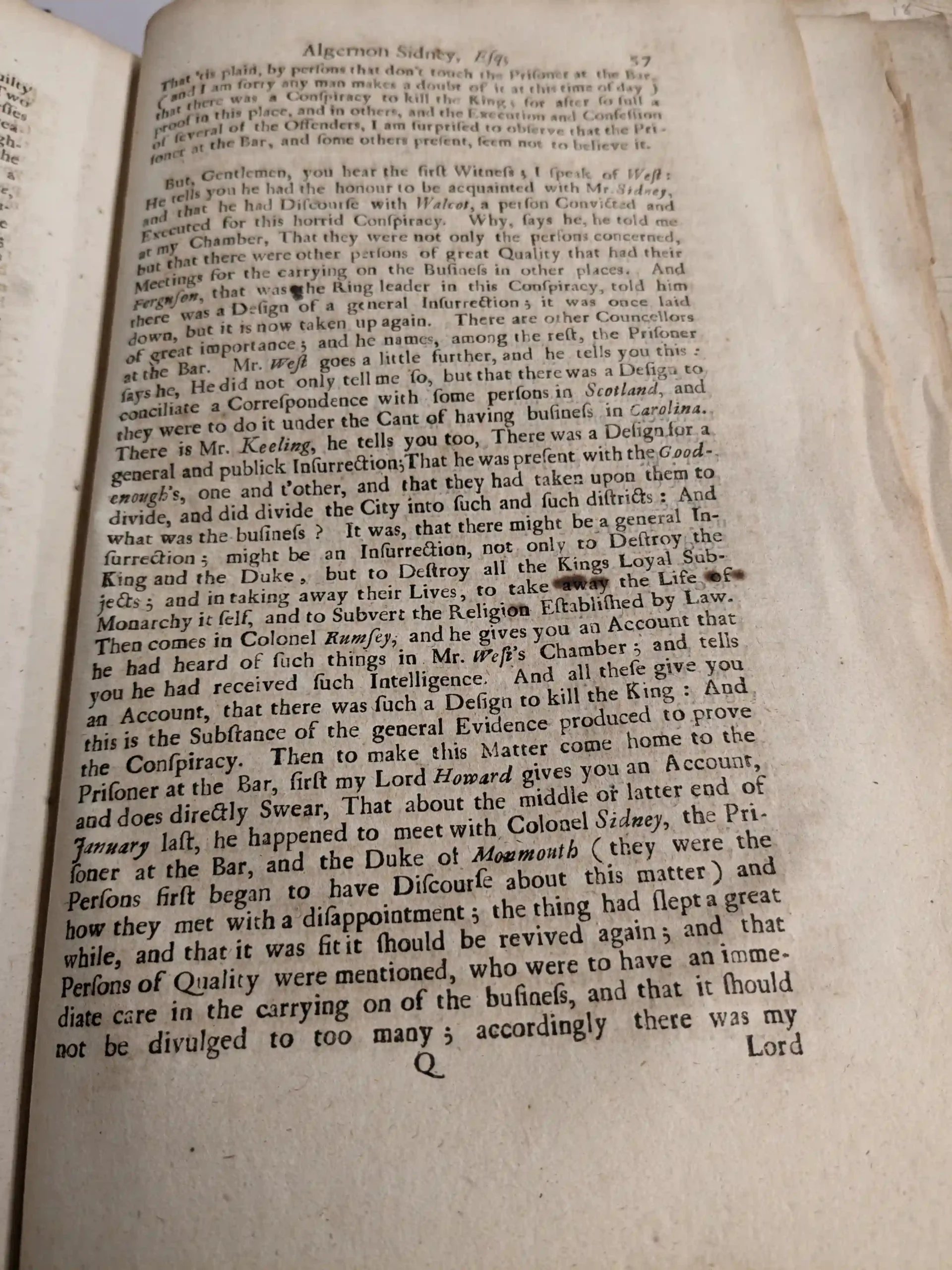

That ’tis plain, by persons that don’t touch the Prisoner at the Bar,

(and I am sorry any man makes a doubt of it at this time of day)

that there was a Conspiracy to kill the King; for after so full a

proof in this place, and in others, and the Execution and Confession

of several of the Offenders, I am surprised to observe that the Pri-

soner at the Bar, and some others present, seem not to believe it.

But, Gentlemen, you hear the first Witness; I speak of West:

He tells you he had the honour to be acquainted with Mr. Sidney,

and that he had Discourse with Walcot, a person Convicted and

Executed for this horrid Conspiracy. Why, says he, he told me

at my Chamber, That they were not only the persons concerned,

but that there were other persons of great Quality that had their

Meetings for the carrying on the Business in other places. And

Ferguson, that was the Ring leader in this Conspiracy, told him

there was a Design of a general Insurrection; it was once laid

down, but it is now taken up again. There are other Councellors

of great importance; and he names, among the rest, the Prisoner

at the Bar. Mr. West goes a little further, and he tells you this:

says he, He did not only tell me so, but that there was a Design to

conciliate a Correspondence with some persons in Scotland, and

they were to do it under the Cant of having business in Carolina.

There is Mr. Keeling, he tells you too, There was a Design for a

general and publick Insurrection; That he was present with the Good-

enough‘s, one and t’other, and that they had taken upon them to

divide, and did divide the City into such and such districts: And

what was the business? It was, that there might be a general In-

surrection; might be an Insurrection, not only to Destroy the

King and the Duke, but to Destroy all the Kings Loyal Sub-

jects; and in taking away their Lives, to take away the Life of

Monarchy it self, and to Subvert the Religion Established by Law.

Then comes in Colonel Rumsey, and he gives you an Account that

he had heard of such things in Mr. West‘s Chamber; and tells

you he had received such Intelligence. And all these give you

an Account, that there was such a Design to kill the King: And

this is the Substance of the general Evidence produced to prove

the Conspiracy. Then to make this Matter come home to the

Prisoner at the Bar, first my Lord Howard gives you an Account,

and does directly Swear, That about the middle or latter end of

January last, he happened to meet with Colonel Sidney, the Pri-

soner at the Bar, and the Duke of Monmouth (they were the

Persons first began to have Discourse about this matter) and

how they met with a disappointment; the thing had slept a great

while, and that it was fit it should be revived again; and that

Persons of Quality were mentioned, who were to have an imme-

diate care in the carrying on of the business, and that it should

not be divulged to too many; accordingly there was my

[58]

Lord Russel, my Lord of Essex, my Lord of Salisbury, and

Mr. Hambden named. He tells you, the Prisoner at the Bar un-

dertook for my Lord of Essex, and Mr. Hambden, and he tells you,

the Duke of Monmouth undertook for my Lord Russel, and the rest;

and that this was the Result of one Meeting: He goes yet further,

That pursuant to this, it was communicated to those persons so to

be ingaged, and the Place and Time was appointed; the Place,

Mr. Hambden‘s House; but is not so positive to the Time, but onely

to the Place, and Persons. He says, all these Persons met, and he

gives you an Accompt, That Mr. Hambden (because it was necessa-

ry for some persons to break silence) gave some short account of

the design of their Meeting, and made some reflections upon the

mischiefs that attended the Government, and what apprehensions;

many people upon the last Choice of Sheriffs, and that there had

been a Male Administration of Publick Justice; That it was fit

some means should be used to redress these Grievances. He can’t tell

you positively, what this man, or that man said there; but says,

that all did unanimously consent to what was then debated about

an Insurrection; and in order to it, they discoursed about the time,

when it should be, and that they thought fit it should be done sud-

denly, while mens minds were wound up to that height, as they

then were; and as the first Witness tells you, There was a Conside-

ration, whether it should be at one place, or at several places toge-

ther: He says, then it was taken into consideration, that this could

not be carried on, but there must be Arms and Ammunition provided.

The next step is, about a necessary concern, the concern of Mo-

ney, and therefore our Law calls Money, The Sinews of War. My

Lord Howard tells you, That the Duke of Monmouth proposed

25. or 30000 l. That my Lord Gray was to advance 10000 l. out of

his own Estate: but then they thought to make their Party more

strong, by the Assistance of a Discontented people in Scotland, my

Lord of Argyle, and Sir John Cockram, and several other people

there to joyn with them. That pursuant to this, all they after met

at my Lord Russels, and the same Debate is Reassumed, and among

the rest, this particular thing of conciliating a friendship with the

Scotch; the Cambels, my Lord of Argyle, and my Lord Melvin were

particularly mentioned. That Coll. Sidney took upon himself to

find out a Messenger, but it was my Lord Russel‘s part to Write the

Letter; One of the Messengers named to convey the same, was

Aaron Smith, he was known, says my Lord Howard, to some of us;

and then we all agreed, that Aaron Smith was the most proper

man: Upon this they brake up that very time. Afterwards comes

my Lord Howard to Coll. Sidney at some distance of time, and he

comes to him, and shews him Threescore Guineys, and told him,

he was going into the City, and that they were to be given to Aaron

Smith. He tells you after this, That he had some other discourse

about a fortnight or three weeks after, with Coll. Sidney; and that

[59]

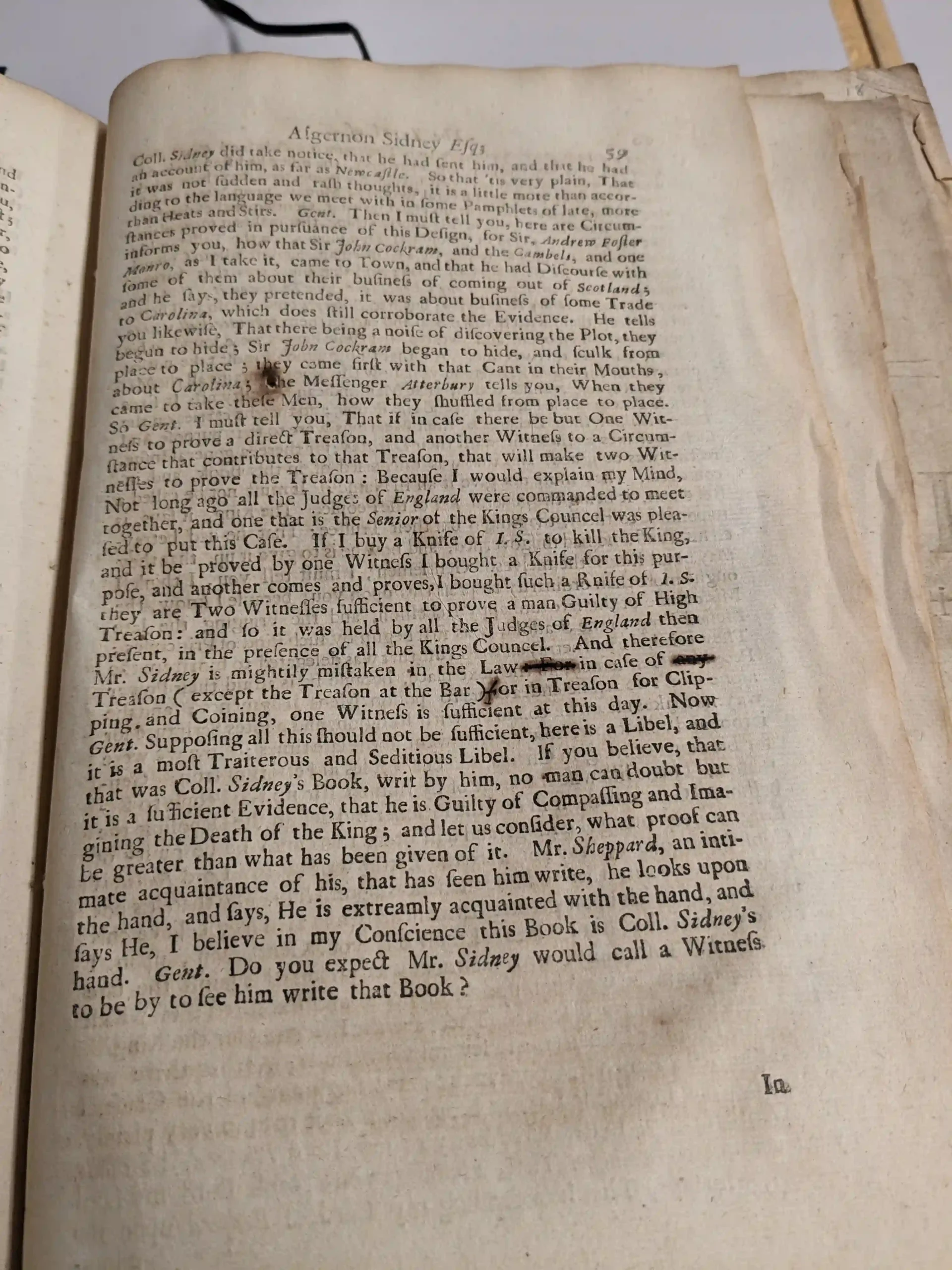

Coll. Sidney did take notice, that he had sent him, and that he had

an account of him, as far as Newcastle. So that ’tis very plain, That

it was not sudden and rash thoughts, it is a little more than accor-

ding to the language we meet with in some Pamphlets of late, more

than Heats and Stirs. Gent. Then I must tell you, here are Circum-

stances proved in pursuance of this Design, for Sir, Andrew Foster

informs you, how that Sir John Cockram, and the Cambels, and one

Monro, as I take it, came to Town, and that he had Discourse with

some of them about their business of coming out of Scotland;

and he say, they pretended, it was about business of some Trade

to Carolina, which does still corroborate the Evidence. He tells

you likewise, That there being a noise of discovering the Plot, they

begun to hide; Sir John Cockram began to hide, and sculk from

place to place; they came first with that Cant in their Mouths,

about Carolina; The Messenger Atterbury tells you, When they

came to take these Men, how they shuffled from place to place.

So Gent. I must tell you, That if in case there be but One Wit-

ness to prove a direct Treason, and another Witness to a Circum-

stance that contributes to that Treason, that will make two Wit-

nesses to prove the Treason: Because I would explain my Mind,

Not long ago all the Judges of England were commanded to meet

together, and one that is the Senior of the Kings Councel was plea-

sed to put this Case. If I buy a Knife of I. S. to kill the King,

and it be proved by one Witness I bought a Knife for this pur-

pose, and another comes and proves, I bought such a Knife of I.S.

they are Two Witnesses sufficient to prove a man Guilty of High

Treason: and so it was held by all the Judges of England then

present, in the presence of all the Kings Councel. And therefore

Mr. Sidney is mightily mistaken in the Law: For in case of any

Treason (except the Treason at the Bar) for in Treason for Clip-

ping and Coining, one Witness is sufficient at this day. Now

Gent. Supposing all this should be sufficient, here is a Libel, and

it is a most Traiterous and Seditious Libel. If you believe, that

that was Coll. Sidney‘s Book, writ by him, no man can doubt but

it is a sufficient Evidence, that he is Guilty of Compassing and Ima-

gining the Death of the King; and let us consider, what proof can

be greater than what has been given of it. Mr. Sheppard, an inti-

mate acquaintance of his, that has seen him write, he looks upon

the hand, and says, He is extreamly acquainted with the hand, and

says He, I believe in my Conscience this Book is Coll. Sidney‘s

hand. Gent. Do you expect Mr. Sidney would call a Witness

to be by to see him write that Book?

[60]

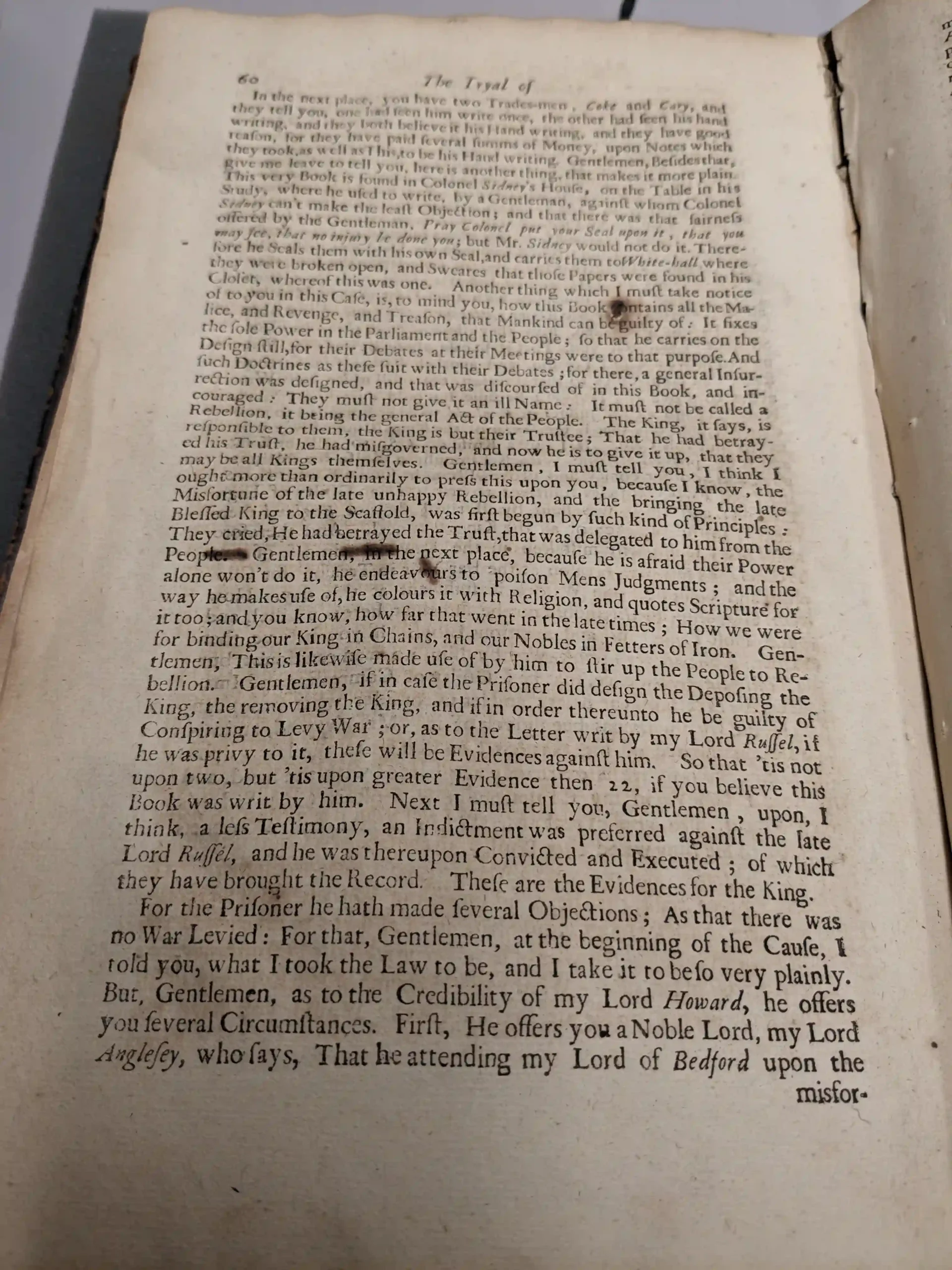

In the next place, you have two Trades-men, Coke and Cary, and

they tell you, one had seen him write once, the other had seen his hand

writing, and they both believe it his Hand writing, and they have good

reason, for they have paid several summs of Money, upon Notes which

they took, as well as This, to be his Hand writing. Gentlemen, Besides that,

give me leave to tell you, here is another thing, that makes it more plain.

This very Book is found in Colonel Sidney‘s House, on the Table in his

Study, where he used to write, by a Gentleman, against whom Colonel

Sidney can’t make the least Objection; and that there was that fairness

offered by the Gentleman, Pray Colonel put your Seal upon it, that you

may see, that no injury be done you; but Mr. Sidney would not do it. There-

fore he Seals them with his own Seal, and carries them to White-hall where

they were broken open, and Sweares that those Papers were found in his

Closet, whereof this was one. Another thing which I must take notice

of to you in this Case, is, to mind you, how this Book contains all the Ma-

lice, and Revenge, and Treason, that Mankind can be guilty of: It fixes

the sole Power in the Parliament and the People; so that he carries on the

Design still, for their Debates at their Meetings were to that purpose. And

such Doctrines as these suit with their Debates; for there, a general Insur-

rection was designed, and that was discoursed of in this Book, and in-

couraged: They must not give it an ill Name: It must not be called a

Rebellion, it being the general Act of the People. The King, it says, is

responsible to them, the King is but their Trustee; That he had betray-

ed his Trust, he had misgoverned, and now he is to give it up, that they

may be all Kings themselves. Gentlemen, I must tell you, I think I

ought more than ordinarily to press this upon you, because I know, the

Misfortune of the late unhappy Rebellion, and the bringing the late

Blessed King to the Scaffold, was first begun by such kind of Principles:

They cried, He had betrayed the Trust, that was delegated to him from the

People. Gentlemen, in the next place, because he is afraid their Power

alone won’t do it, he endeavours to poison Mens Judgments; and the

way he makes use of, he colours it with Religion, and quotes Scripture for

it too; and you know, how far that went in the late times; How we were

for binding our King in Chains, and our Nobles in Fetters of Iron. Gen-

tlemen, This is likewise made use of him to stir up the People to Re-

bellion. Gentlemen, if in case the Prisoner did design the Deposing the

King, the removing the King, and if in order thereunto he be guilty of

Conspiring to Levy War; or, as to the Letter writ by my Lord Russel, if

he was privy to it, these will be Evidences against him. So that ’tis not

upon two, but ’tis upon greater Evidence then 22, if you believe this

Book was writ by him. Next I must tell you, Gentlemen, upon, I

think, a less Testimony, an Indictment was preferred against the late

Lord Russel, and he was thereupon Convicted and Executed; of which

they have brought the Record. These are the Evidences for the King.

For the Prisoner he hath made several Objections; As that there was

no War Levied: For that, Gentlemen, at the beginning of the Cause, I

told you, what I took the Law to be, and I take it to be so very plainly.

But, Gentlemen, as to the Credibility of my Lord Howard, he offers

you several Circumstances. First, He offers you a Noble Lord, my Lord

Anglesey, who says, That he attending my Lord of Bedford upon the

[61]

misfortune of the Imprisonment of his Son; after he had done, my Lord

Howard came to second that part of a Christians Office, which he had

performed, and told him, he had a very good Son, and he knew no harm

of him; and as to the Plot, he knew nothing of it. Another Noble Lord,

my Lord Clare tells you, that he had some Discourse with my Lord How-

ard, and he said, that if he were accused, he thought they would but tell

Noses and his business was done. Then Mr. Philip Howard, he tells you, how

he was not so intimate with him as others, but he often came to his Brothers;

and that he should say he knew nothing of a Plot, nor did he believe any;

but at the same time, he said, he believed there was a Sham Plot: and then

he pressed him about the business of the Address; but that now my Lord of

Essex was out of Town, and so it went off. Another thing Mr. Sidney took

notice of, says he, ’tis an Act of Revenge in my Lord Howard, for he owes

him a Debt, that he does (besides by his Allegation) does not appear.

Col. Sid. My Lord, he hath confessed it.

L. Ch. Just. Admit it; yet in case Collonel Sidney should be Convicted

of this Treason, the Debt accrues to the King, and he can’t be a Farthing

the better for it. But how does it look like Revenge? I find my Lord

Howard, when he speaks of Collonel Sidney, says, he was more beholding

to him than any body, and was more sorry for him; so says my Lord

Clare. Gentlemen, You have it likewise offered, that he came to Collo-

nel Sidney‘s House, and there he was desirous to have the Plate and Goods

removed to his House, and that he would assist them with his Coach and

Coachman to carry them thither; and did affirm, that he knew nothing

of the Plot; and did not believe Colonel Sidney knew any thing: and

this is likewise proved by a couple of Maid Servants, as well as the

French Man. You have likewise some things to the same purpose said by

my Lord Paget, and this is offered to take off the Credibility of my

Lord Howard. Do you believe, because my Lord Howard did not tell

them, I am in a Conspiracy to kill the King; therefore he knew no-

thing of it; he knew these Persons were Men of Honour, and would not

be concerned in any such thing. But do you think, because a Man goes

about and denies his being in a Plot, therefore he was not in it: Nay, it

seems so far from being an Evidence of his Innocence, that ’tis an Evi-

dence of his Guilt. What should provoke a Man to discourse after this

manner, if he had not apprehensions of Guilt within himself? This is

the Testimony offered against my Lord Howard, in disparagement of his

Evidence. Ay, but further its objected, he is in expectation of a Pardon:

And he did say, he thought he should not have the Kings Pardon, till

such time as the drudgery of Swearing was over. Why, Gentlemen, I

take notice, before this Discourse happened, he Swore the same thing at

my Lord Russel‘s Tryal. And I must tell you, though it is the Duty of

every Man to discover all Treasons; yet I tell you, for a Man to come

and Swear himself over and over Guilty, in the face of a Court of Justice,

may seem irksome, and provoke a Man to give it such an Epithet. ‘Tis

therefore for his Credit, that he is an unwilling Witness: But, Gentle-

men, consider, if these things should have been allowed to take away the

Credibility of a Witness, what would have become of the Testimonies, that

have been given of late days? What would become of the Evidence of all

those, that have been so profligate in their Lives? Would you have the

[62]

Kings Council to call none but men, that were not concerned in this Plot, to

prove that they were Plotting? Ay, but Gentlemen, it is further objected,

This Hand looks like an old Hand, and it may not be the Prisoners Hand,

but be Counterfeited; and for that there is a Gentleman, who tells you

what a dexterous Man he is. He says, he believes he could Counterfeit

any Hand in half an hour; ’tis an ugly temptation, but I hope he hath

more Honour than to make use of that Art, he so much glories in. But

what time could there be for the Counterfeiting of this Book? Can you,

imagine that Sir Philip Lloyd through the Bag Sealed up did it? Or, who

else can you imagine should, or, does the Prisoner pretend, did write this

Book? So that as on one side, God forbid, but we should be careful of

Mens Lives, so on the other side, God forbid, that Flourishes and Varnish

should come to indanger the Life of the King, and the Destruction of the

Government. But, Gentlemen, We are not to anticipate you in point

of Fact; I have accordingly to my Memory recapitulated the matters given

in Evidence. It remains purely in you now, whether you do believe up-

on the whole matter, that the Prisoner is Guilty of the High-Treason,

whereof he is Indicted.

Mr. Just. Withins. Gentlemen, ‘Tis fit you should have our Opini-

ons; in all the points of Law we concur with my Lord Chief Justice:

Says Colonel Sidney, here is a mighty Conspiracy, but there is no-

thing comes of it, who must we thank for that? None but the Al-

mighty Providence: One of themselves was troubled in Conscience,

and comes and discovers it, had not Keeling discovered it, God knows

whether we might have been alive at this day.

Then the Jury withdrew, and in about half an hours time returned,

and brought the Prisoner in, Guilty.

And the Lieutenant of the Tower took away his Prisoner.

Munday 26. Nov. 1683. Algernon Sidney, Esquire was

brought up to the Bar of the Court of Kings-bench to re-

ceive his Sentence.

L. Ch. Just. Mr. Attorney, will you move any thing?

Mr. Att. Gen. My Lord, the Prisoner at the Bar is convicted of High

Treason, I demand Judgment against him.

Cl. of Crown. Algernon Sidney. Hold up thy hand (which he did) Thou

hast been Indicted of High Treason, and thereupon arraigned, and there-

unto pleaded not Guilty, and, for thy Tryal, put thy self upon God and

the Country, which Country has found thee Guilty, What can’st thou

say for thy self, Why Judgment of death should not be given against

thee, and execution awarded according to Law?

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I humbly conceive, I have had no Tryal, I

was to be tryed by my Country, I do not find my Country in the

Jury that did try me, There were some of them that were not Free-

holders, I think my Lord, There is neither Law nor President of any

man that has been tryed by a Jury, upon an Indictment lay’d in a County,

that were not Freeholders. So I do humbly conceive: That I have had

no Tryal at all, and if I have had no Tryal, there can be no Judgment.

L. Ch. Just. Mr. Sidney, you had the Opinion of the Court in that

[63]

matter before, We were unanimous in it, for it was the Opinion of all

the Judges of England, in the Case next proceeding yours, tho’ that

was a Case relating to Corporations, but they were of Opinion, that by

the Statute of Queen Mary the Tryal of Treason was put as it was at

Common-Law, and that there was no such Challenge at Common-Law.

Col. Sidney. Under favour, my Lord, I presume in such a Case as this,

of Life, and for what I know concernes every man in England, you will

give me a day and Counsel to argue it.

L. Ch. Just. Tis not in the Power of the Court to do it.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I desire the Indictment against me may be read.

L. Ch. Just. To what purpose?

Col. Sidney. I have somewhat to say to it.

L. Ch. Just. Well, read the Indictment.

Then the Clerk of the Crown read the Indictment.

Col. Sidney. Pray Sir, will you give me leave to see it, if it please you.

L. Ch. Just. No, that we cannot do.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, there is one thing then that makes this abso-

lutely void, It deprives the King of his Title, which is Treason by Law

Defensor fidei. There is no such thing there, if I heard it Right.

L. Ch. Just. In that you would deprive the King of his Life, that is

in very full I think.

Col. Sidney. If no body would deprive the King, no more then I, he

would be in no danger. Under favour these are things not to be over-

ruled in point of Life so easily.

L. Ch. Just. Mr. Sidney, We very well understand our duty, we don’t

need to be told by you what our Duty is, we tell you nothing, but

what is Law, and if you make Objections, that are immaterial, we must

overrule them. Don’t think that we overrule in your Case that we would

not overrule in all mens Cases in your Condition. The Treason is suffi-

ciently lay’d.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I conceive this too, that those words, that are

said to be written in the Paper, that there is nothing of Treason in them;

Besides, that there was nothing at all proved of them, only by similitude

of hands, which upon the Case I alledged to your Lordship, was not to

be admitted in a Criminal Case. Now ’tis easy to call a thing prodito-

rie; but yet let the nature of the thing be examined, I put my self upon

it, that there is no Tresaon in it.

L. Ch. Just. There is not a Line in the Book scarce, but what is Trea-

son.

Mr. Just. Withins. I believe, you don’t believe it Treason.

L. Ch. Just. That is the worst part of your Case; When men are rive-

ted in Opinion, that Kings may be deposed, that they are accomptable

to their People, that a general Insurrection is no Rebellion, and, justifie it,

’tis high time, upon my word, to call them to account.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, the other day I had a book, wherein I had

King James Speech, upon which all that is there, is grounded in his own

Speech to the Parliament in 1603, and there is nothing in these Papers,

which is called a Book, tho’ it never appeared, for if it were true, it was

only Papers found in a private man’s Study, never shew’d to any body;

and Mr. Attorney takes this to bring it to a Crime, in order to some other

[64]

Counsel, and this was to come out such a time, when the Insurrection

brake out. My Lord, There is one Person I did not know where to

find then, but every Body knows where to find now, that is the Duke

of Monmouth; if there had been any thing in Consultation, by this

means to bring any thing about, he must have known of it, for it must

be taken to be in Prosecution of those Designs of his: And if he will say

there ever was any such thing, or knew any thing of it, I will acknow-

ledge whatever you please.

L. Ch. Just. That is over; you were Tryed for this Fact: We must not

send for the Duke of Monmouth.

Col. Sidney. I humbly think I ought, and desire to be heard upon it.

L. Ch. Just. Upon what?

Col. Sidney. If you will call it a Tryal —-

L. Ch. Just. I do. The Law calls it so.

Mr. Just. Withins. We must not hear such Discourses, after you have

been Tryed here, and the Jury have given their Verdict; as if you had

not Justice done you.

Mr. Just. Holloway. I think it was a very fair Tryal.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I desire, That you would hear my Reasons,

why I should be brought to a new Tryal.

L. Ch. Just. That can’t be.

Col. Sidney. Be the Tryal what it will.

Cl. of Cr. Cryer, make an Oyes.

Col. Sidney. Can’t I be heard my Lord?

L. Ch. Just. Yes, If you will speak that which is proper; ’tis a strange

thing. You seem to appeal, as if you had some great hardship upon

you. I am sure, I can as well appeal as you. I am sure you had all

the Favour shewed you, that ever any Prisoner had. The Court heard

you with Patience, when you spake what was proper; but if you begin

to Arraign the Justice of the Nation, it concerns the Justice of the Nation

to prevent you: We are bound by our Consciences and our Oaths to see

right done to you; and tho’ we are Judges upon Earth, we are accomptable

to the Judge of Heaven and Earth; and we act according to our Consciences,

tho’ we don’t act according to your Opinion.

Col. Sid. My Lord, I say. In the first place I was brought to West-

minster by Habeas Corpus, the 7th of this Month, granted the day before

to be Arraigned, when yet no Bill was exhibited against me; and my

Prosecutors could not know it would be found, unless they had a Corre-

spondence with the Grand Jury, which under favour ought not to have

been had.

L. Ch. Just. We know nothing of it: You had as good tell us of some-

bodies Ghost, as you did at the Tryal.

Col. Sid. I told you of two infamous Persons that had acted my Lord

Russel‘s Ghost.

L. Ch. Just. Go on, if you have any thing else.

Col. Sid. I prayed a Copy of the Indictment, making my Objections

against it, and putting in a special Plea, which the Law, I humbly con-

ceive allowed me: the help of Counsel to frame it was denied.

L. Ch. Just. For the Copy of the Indictment, it was denied in the Case

you cited. This favour shewed you to day, was denied at any time to

[65]

Sir Henry Vane, that is to have the Indictment read in Latin. Don’t say

on the other side, we refused your Plea. I told you, have a care of put-

ting it in. If the Plea was such as Mr. Attorney did demurre to it. I told

you, you were answerable for the Consequences of it.

Mr. Just. Withins. We told you, you might put it in, but you must

put it in at your Peril.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I would have put it in.

L. Ch. Just. I did advertise you. If you put in a Plea, upon your Peril

be it. I told you, We are bound by Law to give you that fair advertise-

ment of the great danger you would fall under, if it were not a good

Plea.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, my Plea was that, could never hurt me.

L. Ch. Just. We do not know that.

Col. Sid. I desire, my Lord, this, that it may be considered, That,

being brought here to my Tryal, I did desire a Copy of my Indictment,

upon the Statute of 46. E. 3. which does allow it to all Men in all Cases.

L. Ch. Just. I tell you the Law is otherwise, and told you so then,

and tell you so now.

Col. Sid. Your Lordship did not tell me, That was not a Law.

L. Ch. Just. Unless there be a Law particular for Col. Sidney. If you

have any more to say —-

Col. Sid. I am probably informed, and, if your Lordship will give me

time, shall be able to prove it, That the Jury was not summoned, as it

ought to be: My Lord, if this Jury was not summoned by the Bailiffe,

according to the ordinary way, but they were agreed upon by the Un-

der-Sheriff, Graham, and Burton, I desire to know, whether that be a good

Jury?

L. Ch. Just. We can take notice of nothing, but what is upon the Re-

cord: Here is a Return by the Sheriff; if there had been any indirect

means used with the Sheriff, or any else, you should have mentioned it,

before they were Sworn.

Col. Sid. Is there any thing in the World more irregular then that?

L. Ch. Just. I know nothing of it. That time is past.

Col. Sid. Now, my Lord, All men are admitted on the Jury.

L. Ch. Just. Why, you did not like Galt, and now you don’t like those

that you had. In plain English, if any Jury had found you Guilty it

had been the same thing. It had been a good Summons, if they had ac-

quitted you.

Col. Sidney. When the Jury, thus composed, was sworne, 4 witnesses,

of whom 3 were under the terror of Death for Treasons, were produc’d

against me. And they confessed themselves guilty of Crimes, of which

I had no knowledge, and told storys by hear-say. And your Lordship

did promise in summing up the Evidence, that the Jury should be in-

formed what did reach me, and what not, and I don’t remember that

was done.

L. Ch. Just. I did it particularly, I think I was as careful of it as possi-

bly I could be.

Col. Sidney. My Lord Howard being the only Witness, that say’d any

thing against me; Papers, which were sayd to be found in my house, were

produced as another Witness, and no other Testimony given concerning

[66]

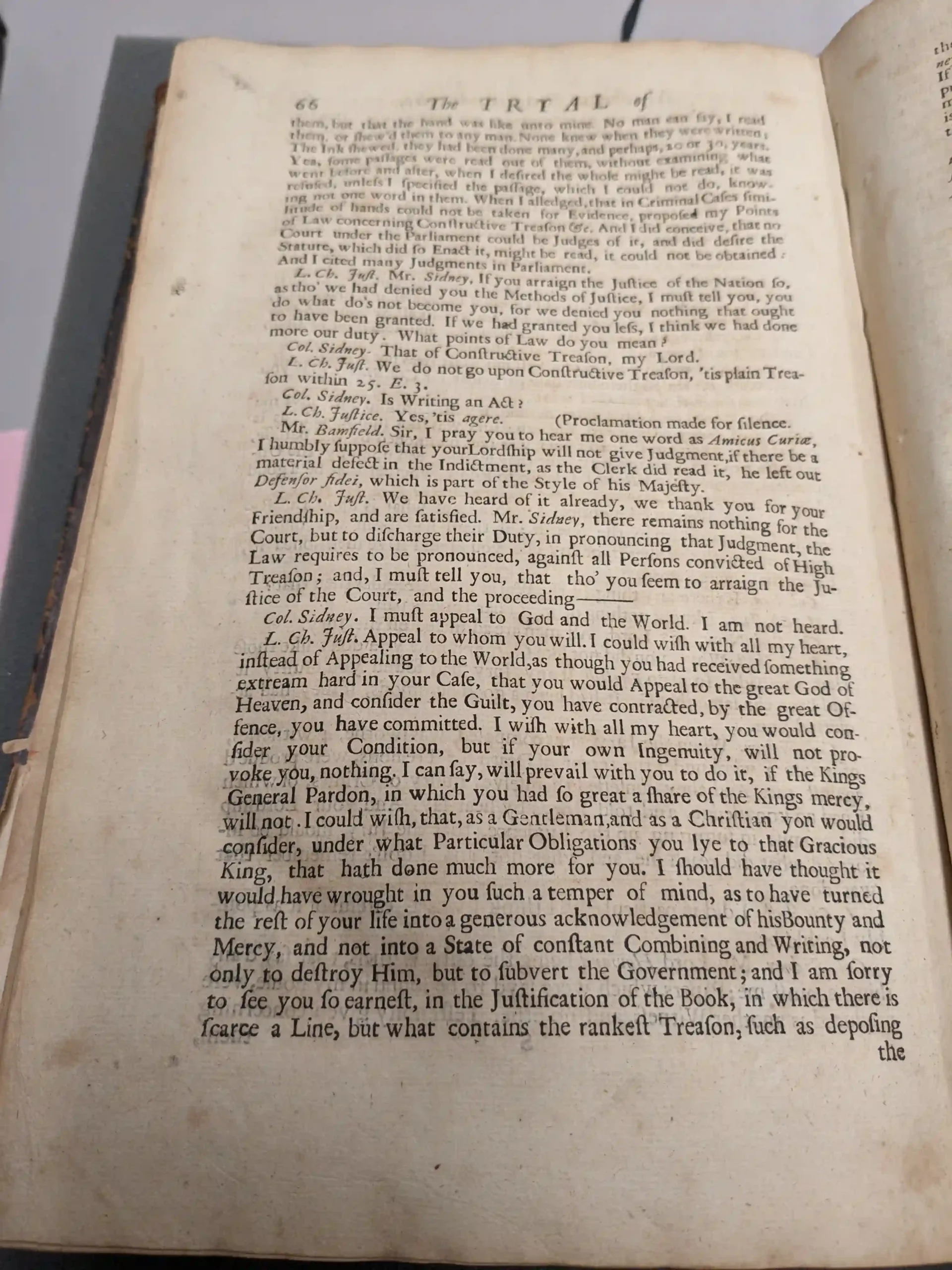

them, but that the hand was like unto mine. No man can say, I read

them, or shew’d them to any man. None knew when they were written;

The Ink shewed, they had been done many, and perhaps, 20 or 30, years.

Yea, some passages were read out of them, without examining what

went before and after, when I desired the whole might be read, it was

refused, unless I specified the passage, which I could not do, know-

ing not one word in them. When I alledged, that in Criminal Cases simi-

litude of hands could not be taken for Evidence, proposed by Points

of Law concerning Constructive Treason &c. And I did conceive, that no

Court under the Parliament could be Judges of it, and did desire the

Statute, which did so Enact it, might be read, it could not be obtained:

And I cited many Judgments in Parliament.

L. Ch. Just. Mr. Sidney, If you arraign the Justice of the Nation so,

as tho’ we had denied you the Methods of Justice, I must tell you, you

do what do’s not become you, for we denied you nothing that ought

to have been granted. If we had granted you less, I think we had done

more our duty. What points of Law do you mean?

Col. Sidney. That of Constructive Treason, my Lord.

L. Ch. Just. We do not go upon Constructive Treason, ’tis plain Trea-

son within 25. E. 3.

Col. Sidney. Is Writing an Act?

L. Ch. Justice. Yes, ’tis agere. (Proclamation made for silence.

Mr. Bamfield. Sir, I pray you to hear me one word as Amicus Curiæ,

I humbly suppose that your Lordship will not give Judgement, if there be a

material defect in the Indictment, as the Clerk did read it, he left out

Defensor fidei, which is part of the Style of his Mjaesty.

L. Ch. Just. We have heard of it already, we thank you for your

Friendship, and are satisfied. Mr. Sidney, there remains nothing for the

Court, but to discharge their Duty, in pronouncing that Judgment, the

Law requires to be pronounced, against all Persons convicted of High

Treason; and I must tell you, that tho’ you seem to arraign the Ju-

stice of the Court, and the proceeding —-

Col. Sidney. I must appeal to God and the World. I am not heard.

L. Ch. Just. Appeal to whom you will. I could wish with all my heart,

instead of Appealing to the World, as though you had received something

extream hard in your Case, that you would Appeal to the great God of

Heaven, and consider the Guilt, you have contracted, by the great Of-

fence, you have committed. I wish with all my heart, you would con-

sider your Condition, but if your own Ingenuity, will not pro-

voke you, nothing I can say, will prevail with you to do it, if the Kings

General Pardon, in which you had so great a share of the Kings mercy,

will not. I could wish, that, as a Gentleman, and as a Christian you would

consider, under what Particular Obligations you lye to that Gracious

King, that hath done much more for you. I should have thought it

would have wrought in you such a temper of mind, as to have turned

the rest of your life into a generous acknowledgement of his Bounty and

Mercy, and not into a State of constant Combining and Writing, not

only to destroy Him, but to subvert the Government; and I am sorry

to see you so earnest, in the Justification of the Book, in which there is

scarce a Line, but what contains the rankest Treason, such as deposing

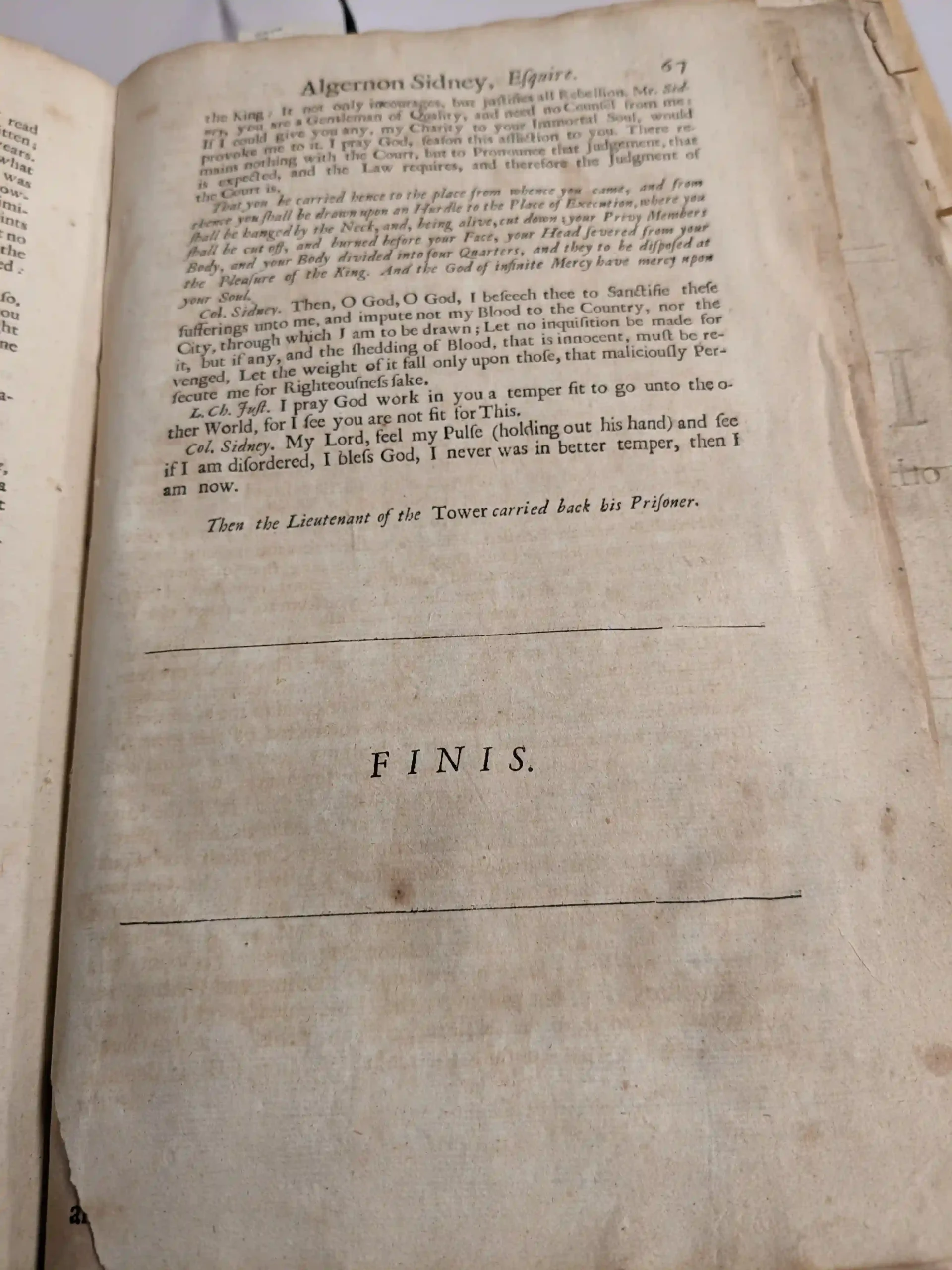

[67]

the King: It not only incourages, but justifies all Rebellion. Mr. Sid-

ney, you are a Gentleman of Quality, and need no Counsel from me:

If I could give you any, my Charity to your Immortal Soul, would

provoke me to it. I pray God, season this affliction to you. There re-

mains nothing with the Court, but to Pronounce that Judgement, that

is expected, and the Law requires, and therefore the Judgment of

the Court is,

That you be carried hence to the place from whence you came, and from

thence you shall be drawn upon an Hurdle to the Place of Execution, where you

shall be hanged by the Neck, and, being alive, cut down; your Privy Members

shall be cut off, and burned before your Face, your Head severed from your

Body, and your Body divided into four Quarters, and they to be disposed at

the Pleasure of the King. And the God of infinite Mercy have mercy upon

your Soul.

Col. Sidney. Then, O God, O God, I beseech thee to Sanctifie these

sufferings unto me, and impute not my Blood to the Country, nor the

City, through which I am to be drawn; Let no inquisition be made for

it, but if any, and the shedding of Blood, that is innocent, must be re-

venged, Let the weight of it fall only upon those, that maliciously Per-

secute me for Righteousness sake.

L. Ch. Just. I pray God work in you a temper fit to go unto the o-

ther World, for I see you are not fit for This.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, feel my Pulse (holding out his hand) and see

if I am disordered, I bless God, I never was in better temper, then I

am now.

Then the Lieutenant of the Tower carried back his Prisoner.

FINIS.

THE

PROCEEDINGS to Sentence of Death,

AGAINST

Algernon Sidny Esq;

Who was Convicted of HIGH-TREASON,

(On the 21 of November 1683.) at the Kings-

Bench-Bar, for Conspiring the Death of the

King, to Subvert the Government, &c.

Being an Account of what Remarkably

passed on that Occasion.

ALgeron Sidny Esq; having on the seventh of this Instant,

November, been Arraigned at the Barr of the Court of

Kings-Bench, upon an Indictment of High-Treason found

by the Grand Jurors, and thereto pleaded not Guilty; he on

the 21 Instant was brought again to the said Barr in Order to his

Tryal, where having made exceptions against some of the Jury,

then Summoned to Try the Issue between the King and him,

for not being Free-holders in the County, and against others, up-

on divers other objections, a Jury of Twelve were Sworn, after

he had Peremptorily Challenged 34 whereupon the Indictment

was Read, and the Treason therein mention opened by the Kings

Council, tending to the destruction of the King, the Suburtion of

the Government, and the Establishing a Common-Wealth, by

utterly Abolishing and Exterprating Monarchy; after which Mr.

West, Collonel Rumsey, and Mr. Keeling being Sworn proved the

Plot in general, and the Lord Howard in particular as to the Pri-

soner proving him to have been at divers Consults consenting to a

Rising and sending Aron Smith into Scotland, proposing a form of

Government after Monarchy should be Suppressed, &c. Then Sir

Phillip Lloyd proved a Treasonable Libell found in the Prisoners

House, tending to the deposing of the King and Setling the

Power in the People, with many other Treasonable Tenents and

Assertions, which he denying; further proof was made by Mr.

Shepherd, Mr. Cook, and Mr. Cary, Men that had had dealings

with Mr. Sidny, that it was (as they verily believed) his Hand

Writing, upon proof of these Treasons at large, notwithstanding

the objections he had made against the Lord Howards Evidence, and

some discourses in Relation to the Pamphlet or Libell; He upon

the Evidences being Summed up as well on the one side as the

other, and the charge given, was found Guilty of High-Treason;

and Remanded to the Tower.

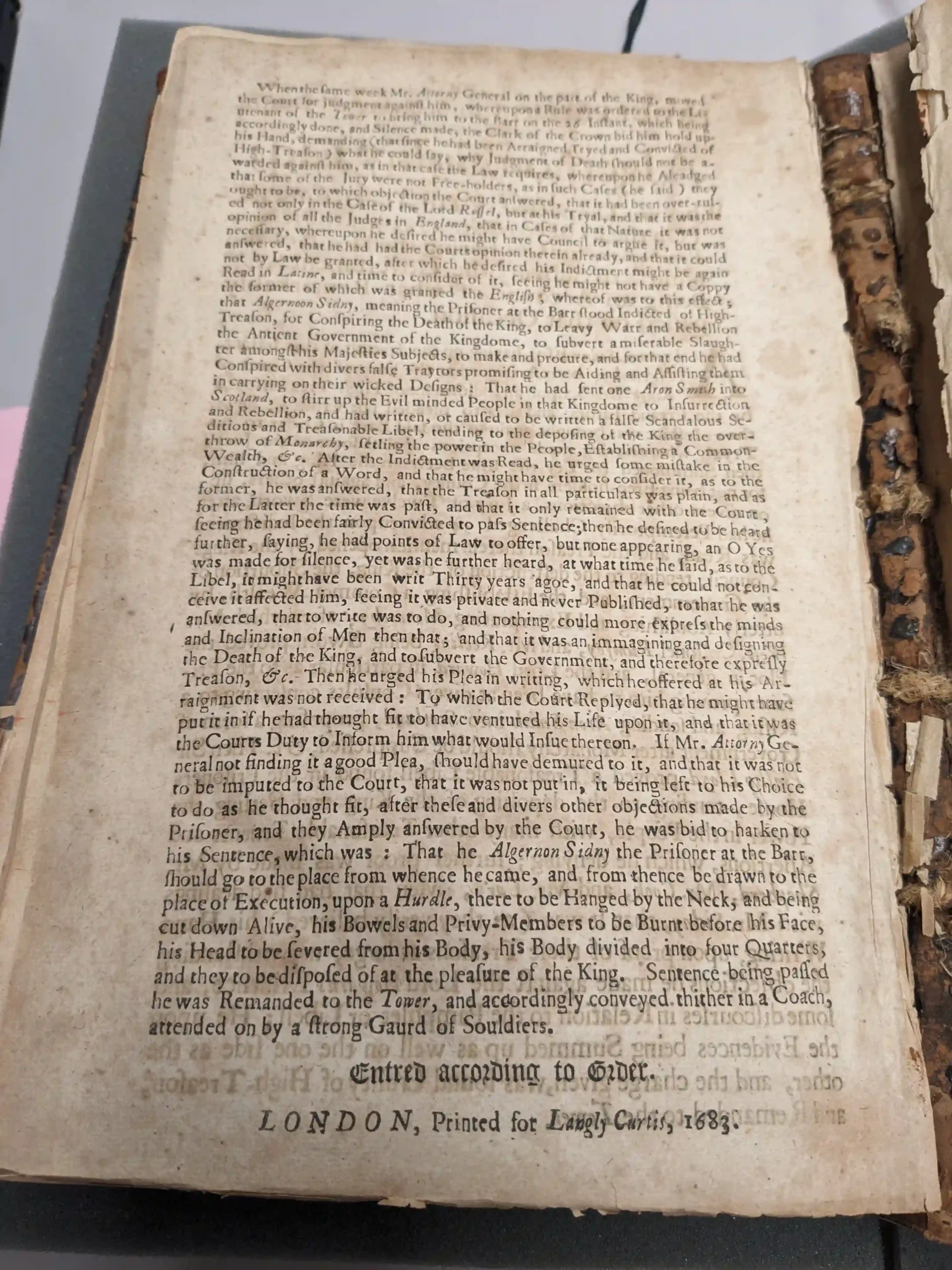

When the same week Mr. Attorny General on the part of the King, moved

the Court for judgment against him, whereupon a Rule was ordered to the Li-

utenant of the Tower to bring him to the Barr on the 26 Instant, which being

accordingly done, and Silence made, the Clark of the Crown bid him hold up

his Hand, demanding (that since he had been Arraigned, Tryed and Convicted of

High-Treason) what he could say, why Judgment of Death should not be a-

warded against him, as in that case the Law requires, whereupon he Aleadged

that some of the Jury were not Free-holders, as in such Cases (he said) they

ought to be, to which objection the Court answered, that it had been over-rul-

ed not only in the Case of the Lord Russel, but at his Tryal, and that it was the

opinion of all the Judges in England, that in Cases of that Nature it was not

necessary, whereupon he desired he might have Council to argue it, but was

answered, that he had had the Courts opinion therein already, and that it could

not by Law be granted, after which he desired his Indictment might be again

Read in Latine, and time to consider of it, seeing he might not have a Coppy

the former of which was granted the English; whereof was to this effect;

that Algernoon Sidny, meaning the Prisoner at the Bar stood Indicted of High-

Treason, for Conspiring the Death of the King, to Leavy Warr and Rebellion

the Antient Government of the Kingdome, to subvert a miserable Slaugh-

ter amongst his Majesties Subjects, to make and procure, and for that end he had

Conspired with divers false Traytors promising to be Aiding and Assisting them

in carrying on their wicked Designs: That he had sent one Aron Smith into

Scotland, to stirr up the Evil minded People in that Kingdome to Insurrection

and Rebellion, and had written, or caused to be written a false Scandalous Se-

ditous and Treasonable Libel, tending to the deposing of the King the over-

throw of Monarchy, setling the power in the People, Establishing a Common-

Wealth, &c. After the Indictment was Read, he urged some mistake in the

Construction of a Word, and that he might have time to consider it, as to the

former, he was answered, that the Treason in all particulars was plain, and as

for the Latter the time was past, and that it only remained with the Court,

seeing he had been fairly Convicted to pass Sentence; then he desired to be heard

further, saying, he had points of Law to offer, but none appearing, an O Yes

was made for silence, yet was he further heard, at what time he said, as to the

Libel, it might have been writ Thirty years agoe, and that he could not con-