The Arraignment, Tryal & Condemnantion of Algernon Sidney – 2

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

[19]

son to be sent thither to Unite us into one Sence and Care. This

is as much as Occurs to my Memory upon that Meeting. About

a Fortnight or three Weeks after, which I suppose carried it to the

middle of February next we had another Meeting, and that was at

Southampton House at my Lord Russels, and there was every one of

the same Persons; and when we came there, there happened to fall

in a Discourse which I know not how it came in, but it was a little

warmly urged, and thought to be untimely, and unseasonable; and

that I remember was by Mr. Hambden, who did tell us, That ha-

ving now United our selves into such an Undertaking as this was,

it could not but be expected, that it would be a Question put to

many of us; To what End all this was? Where it was we inten-

ded to Terminate? Into what we intended to Resolve? That these

were Questions he met with; and it was probable, every one had

or would meet with from those Persons, whose Assistance we ex-

pected; and that if there was any thing of a Personal Interest de-

signed or intended, that there were but very few of those, whose

Hearts were now with us, but would fall off: And therefore, since

we were upon such an Undertaking, we should resolve our selves

into such Principles, as should put the Properties and Liberties of

the People into such Hands, as it should not be easily Invaded by

any that were Trusted with the Supream Authority of the Land;

and it was mentioned to Resolve all into the Authority of the Par-

liament. This was moved by him, and had a little harshness to

some that were there; but yet upon the whole Matter we general-

ly consented to it, That it was nothing but a Publick Good that we

all intended. But then after that, We fell to that which we char-

ged our selves with at the first Meeting, and that was concerning

tending into Scotland, and of settling an Understanding with my

Lord of Argyle: And in order to this, it was necessary to send a

Messenger thither to some Persons, whom we thought were the

most leading Men of the Interest in Scotland. This led us to the

insisting on some particular Persons; the Gentlemen named, were

my Lord Melvin, Sir John Cockram, and the Cambells; l and I am sure

it was some of the Alliance of my Lord of Argyle, and I think of

the Name. As soon as this was propounded, it was offered by this

Gentleman Collonel Sidney, that he would take the Care of the

Person; and he had a Person in his Thoughts, that he thought a

very fit Man to be instrusted; one or two, but one in special, and

he named Aaron Smith to be the Man, who was known to some

of us, to others not; I was one that did know him, and as many as

knew him, thought him a proper Person. This is all that Occurs

to me that was at the second Meeting, and they are the only

Consults that I was at.

Mr. Att. Gen. What was he to do?

Lord Howard. There was no particular Deed for him, more

than to carry a Letter. The Duke of Monmouth undertook to bring

my Lord Melvin hither, because he had a particular dependance

upon him, and I think some Relation to his Lady: But to Sir John

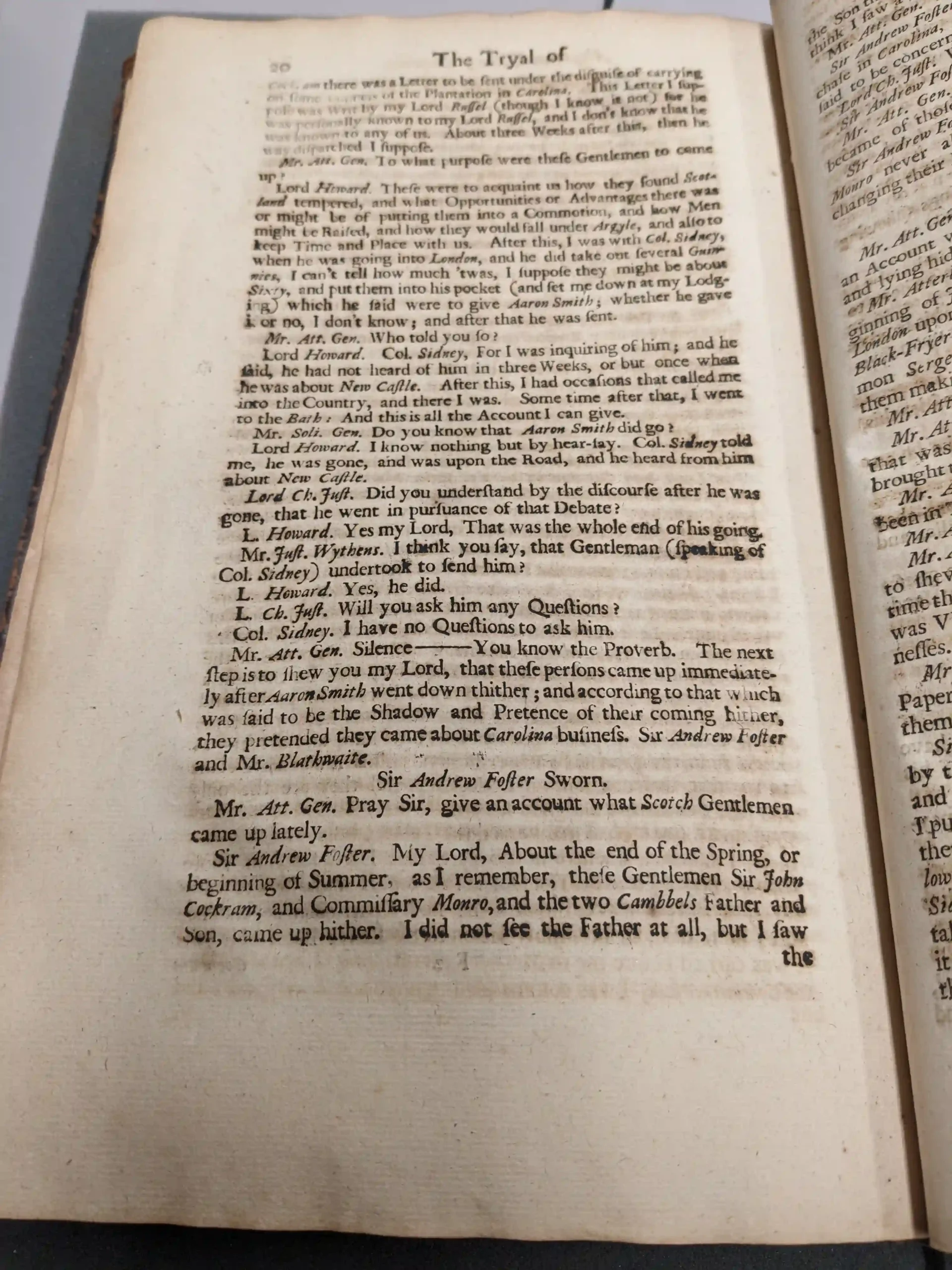

[20]

Cockram there was a Letter to be sent under the disguise of carrying

on some Business of the Plantation in Carolina. This Letter I sup-

pose was Writ by my Lord Russel (though I know it not) for he

was personally known to my Lord Russel, and I don’t know that he

was known to any of us. About three Weeks after this, then he

was dispatched I suppose.

Mr. Att. Gen. To what purpose was these Gentlemen to come

up?

Lord Howard. These were to acquaint us how they found Scot-

land tempered, and what Opportunities or Advantages there was

or might be of putting them into a Commotion, and how Men

might be Raised, and how they would fall under Argyle, and also to

keep Time and Place with us. After this, I was with Col. Sidney,

when he was going into London, and he did take out several Guin-

nies, I can’t tell how much ’twas, I suppose they might be about

Sixty, and put them into his pocket (and set me down at my Lodg-

ing) which he said were to give Aaron Smith; whether he gave

it or no, I don’t know; and after that he was sent.

Mr. Att. Gen. Who told you so?

Lord Howard. Col. Sidney, For I was inquiring of him; and he

said, he had not heard of him in three Weeks, or but once when

he was about New Castle. After this, I had occasions that called me

into the Country, and there I was. Some time after that, I went

to the Bath : And this is all the Account I can give.

Mr. Soli. Gen. Do you know that Aaron Smith did go?

Lord Howard. I know nothing but by hear-say. Col Sidney told

me, he was gone, and was upon the Road, and he heard from him

about New Castle.

Lord Ch. Just. Did you understand by the discourse after he was

gone, that he went in pursuance of that Debate?

L. Howard. Yes my Lord, That was the whole end of his going.

Mr. Just. Wythens. I think you say, that Gentleman (speaking of

Col. Sidney) undertook to send him?

L. Howard. Yes, he did.

L. Ch. Just. Will you ask him any Questions?

Col. Sidney. I have no Questions to ask him.

Mr. Att. Gen. Silence —- You know the Proverb. The next

step is to shew you my Lord, that these persons came up immediate-

ly after Aaron Smith went down thither; and according to that which

was said to be the Shadow and Pretence of their coming hither,

they pretended they came about Carolina business. Sir Andrew Foster

and Mr. Blathwaite.

Sir Andrew Foster Sworn.

Mr. Att. Gen. Pray Sir, give an account what Scotch Gentlemen

came up lately.

Sir Andrew Foster. My Lord, About the end of Spring, or

beginning of Summer, as I remember, these Gentlemen Sir John

Cockram, and Commissary Monro, and the two Cambbels Father and

Son, came up hither. I did not see the Father at all, but I saw

[21]

the Son the day of the Lord Russels Tryal; but the other two, I

think I saw a little before the Discovery of the Plot.

Mr. Att. Gen. What did they pretend they came about?

Sir Andrew Foster. They pretended they came to make a Pur-

chase in Carolina, and I saw their Commission from the Persons

said to be concern’d in that Design.

Lord Ch. Just. Who do you speak of?

Sir Andrew Foster. Sir John Cockram and Commissary Monro.

Mr. Att. Gen. As soon as the Rumour came of the Plot, What

became of those Gentlemen?

Sir Andrew Foster. Sir John Cockram absconded, but Commissary

Monro never absconded, and the Cambels I heard were seized,

changing their Lodging from place to place.

Mr. Atterbury Sworn.

Mr. Att. Gen. Mr. Atterbury, Will you give my Lord and the Jury

an Account what you know of these Scotch men, their absconding

and lying hid.

Mr. Atterbury. My Lord, Upon the latter end of June, or the be-

ginning of July; the beginning of July it was, I was sent for into

London upon a discovery of some Scotch Gentlemen that lay about

Black-Fryers; and when I came down there, there was the Com-

mon Sergeant and some others, had been before me, and found

them making an escape into a Boat.

Mr. Att. Gen. Who were they?

Mr. Atterbury. Sir Hugh Cambel, and Sir John Cockram, and one

that was committed to the Gate-House by the Counsel as soon as

brought thither.

Mr. Att. Gen. We shall end here, my Lord: How long had they

been in Town?

Mr. Atterbury. They had been in Town some little time.

Mr. Att. Gen. We have done with this piece of our Evidence. Now

to shew that while this Emissary was in Scotland, at the same

time the Colonel (which will be another Overt Act of the Treason)

was Writing a Treasonable Pamphlet. I will call you the Wt-

nesses. It is all of his own writings. Sir Philip Lloyd.

Mr. Att. Gen. Sir Philip Lloyd, Pray will you look upon those

Papers, and give my Lord and the Jury an account where you found

them.

Sir Philip Lloyd. I had a Warrant my Lord, from the Secretary

by the King and Council, to seize Mr. Algernon Sidney‘s Papers;

and pursuant to it, I did go to his House, and such as I found there

I put up. I found a great many upon the Table, amongst which were

these, I suppose it is where he usually writes, I put them in a Pil-

lowbear I borrowed in the House, and that in a Trunk; I desired Coll.

Sidney would put his Seal upon them, that there should be no mis-

take; he refused, so I took my Seal, and Sealed up the Trunk, and

it was carried before me to Mr. Secretary Jenkins Office. When

the Committee sate, I was commanded to undo the Trunk, and I did

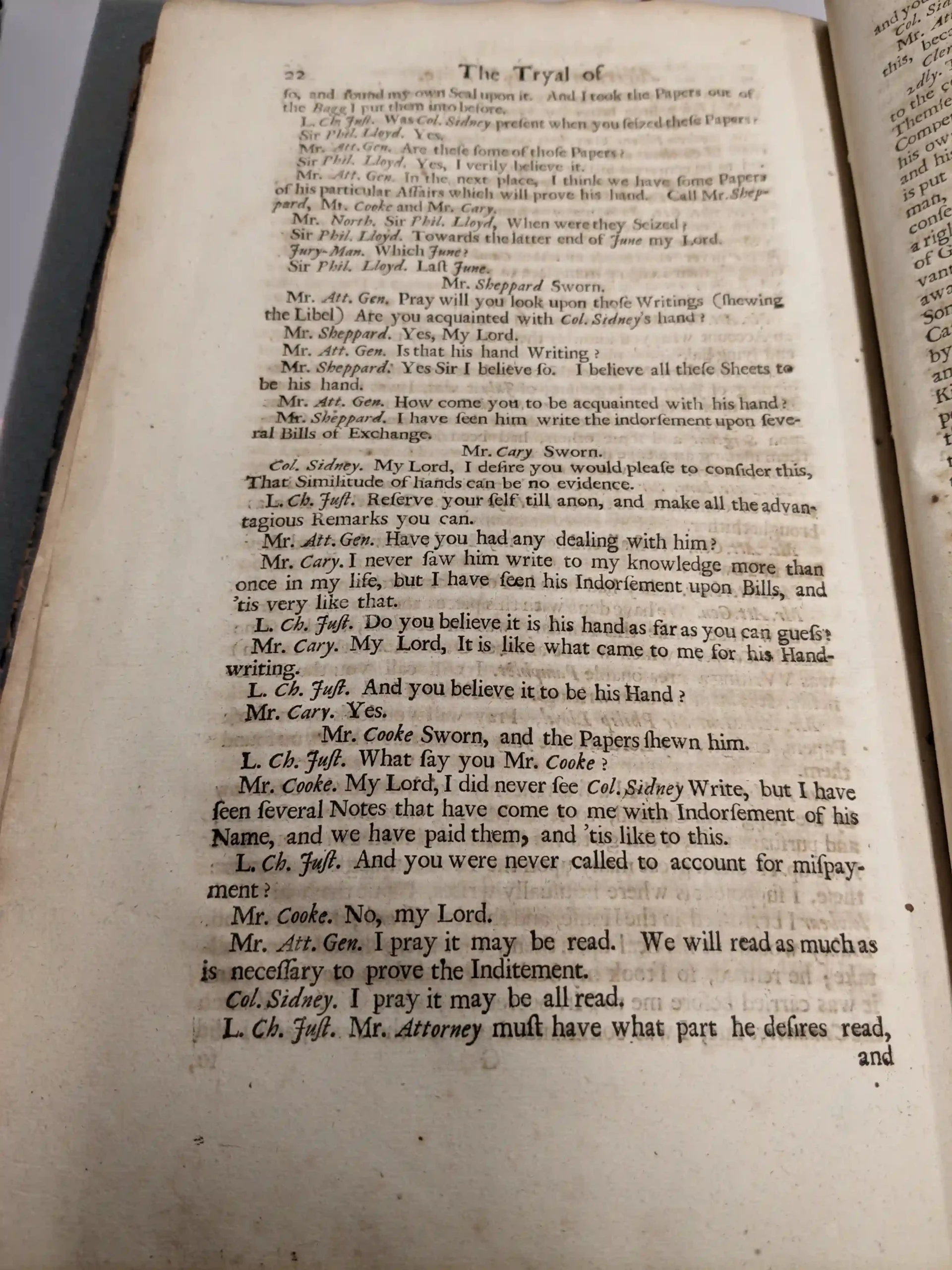

[22]

so, and found my own Seal upon it. And I took the Papers out of

the Bagg, I put them into before.

L. Ch. Just. Was Col. Sidney present when you seized these Papers?

Sir Phil. Lloyd. Yes.

Mr. Att. Gen. Are these some of those Papers?

Sir Phil. Lloyd. Yes, I verily believe it.

Mr. Att. Gen. In the next place, I think we have some Papers

of his particular Affairs which will prove his hand. Call Mr. Shep-

pard, Mr. Cooke and Mr. Cary.

Mr. North, Sir Phil. Lloyd, When were they Seized?

Sir Phil. Lloyd. Towards the latter end of June my Lord.

Jury-Man. Which June?

Sir Phil. Lloyd. Last June.

Mr. Sheppard Sworn.

Mr. Att. Gen. Pray will you look upon these Writings (shewing

the Libel) Are you acquainted with Col. Sidney‘s hand?

Mr. Sheppard. Yes, My Lord.

Mr. Att. Gen. Is that his hand Writing?

Mr. Sheppard. Yes Sir I believe so. I believe all these Sheets to

be his hand.

Mr. Att. Gen. How come you to be acquainted with his hand?

Mr. Sheppard. I have seen him write the indorsement upon seve-

ral Bills of Exchange.

Mr. Cary Sworn.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I desire you would please to consider this,

That Similitude of hands can be no evidence.

L. Ch. Just. Reserve your self till anon, and make all the advan-

tagious Remarks you can.

Mr. Att. Gen. Have you had any dealing with him?

Mr. Cary. I never saw him write to my knowledge more than

once in my life, but I have seen his Indorsement upon Bills, and

’tis very like that.

L. Ch. Just. Do you believe it is his hand as far as you can guess?

Mr. Cary. My Lord, It is like what came to me for his Hand-

writing.

L. Ch. Just. And you believe it to be his Hand?

Mr. Cary. Yes.

Mr. Cooke Sworn, and the Papers shewn him.

L. Ch. Just. What say you Mr. Cooke?

Mr. Cooke. My Lord, I did never see Col. Sidney Write, but I have

seen several Notes that have come to me with Indorsement of his

Name, and we have paid them, and ’tis like to this.

L. Ch. Just. And you were never called to account for mispay-

ment?

Mr. Cooke. No, my Lord.

Mr. Att. Gen. I pray it may be read. We will read as much as

is necessary to prove the Inditement.

Col. Sidney. I pray it may be all read.

L. Ch. Just. Mr. Attorney must have what part he desires read,

[23]

and you shall have what part you will have read afterwards.

Col. Sidney. I desire all may be read.

Mr. Att. Gen. Begin there. Secondly, There was no Absurdity in

this, because it was their own Case.

Clerk Reads.

2dly. There was no Absurdity in this, tho it was their own Case; but

to the contrary, because it was their own Case: that is, concerning

Themselves only, and they had no Superiour. They only were the

Competent Judges, they decided their Controversies, as every man in

his own Family doth, such as arise between Him and his Children,

and his Servants. This Power hath no other restriction, than what

is put upon it by the municipal Law of the Country, where any

man, and that hath no other force, than as he is understood to have

consented unto it. Thus in England every man (in a Degree) hath

a right of Chastizing them; and in many places (even by the Law

of God) the Master hath a power of Life and Death over his Ser-

vant: It were a most absurd Folly, to say, that a man might not put

away, or in some places kill an Adulterous Wife, a Disobedient

Son, or an Unlawful Servant, because he is Party and Judge; for the

Case doth admit of no other, unless he had abridged his own right

by entring into a Society, where other Rules are agreed upon,

and a Superiour-Judge constituted, there being none such between

King and People: That People must needs be the Judg of things hap-

pening between Them and Him whom they did not constitute, that

they might be Great, Glorious, and Rich; but that they might Judge

them, and fight their Battles; or otherwise do good unto them as

they should direct. In this sence, he that is Singulis Major, and

ought to be obliged by every man, in his Just and Lawful com-

mands tending to the Publick Good: And must be suffered to do

nothing against it, nor in any respect more than the Law doth allow.

For this Reason Bracton saith, that the King hath three Superiours,

to wit, Deum Legem & Parliament‘ ; that is, the Power Originally

in the People of England, is delegated unto the Parliament. He is

subject unto the Law of God as he is a man to the people that makes

him a King, in as much as he is a King: the Law sets a measure unto

that Subjection, and the Parliament Judges of the particular Cases

thereupon arising: He must be content to submit his Interest unto

Theirs, since he is no more than any one of them, in any other respect

than that He is by the Consent of all, raised above any other.

If he doth not like this Condition, he may renounce the Crown;

but if he receive it upon that Condition, (as all Magistrates do

the Power they receive) and Swear to perform it, He must expect

that the Performance will be Exacted, or Revenge taken by those

that he hath Betrayed.

If this be not so, I desire to know of our Author, how one or more

men can come to be guilty of Treason against the KING, As Lex fa-

cit ut fit Rea. No man can owe more unto him than unto any other;

or he unto every other man by any rule but the Law; and if he

must not be Judg in his own Case, neither he nor any other by Pow-

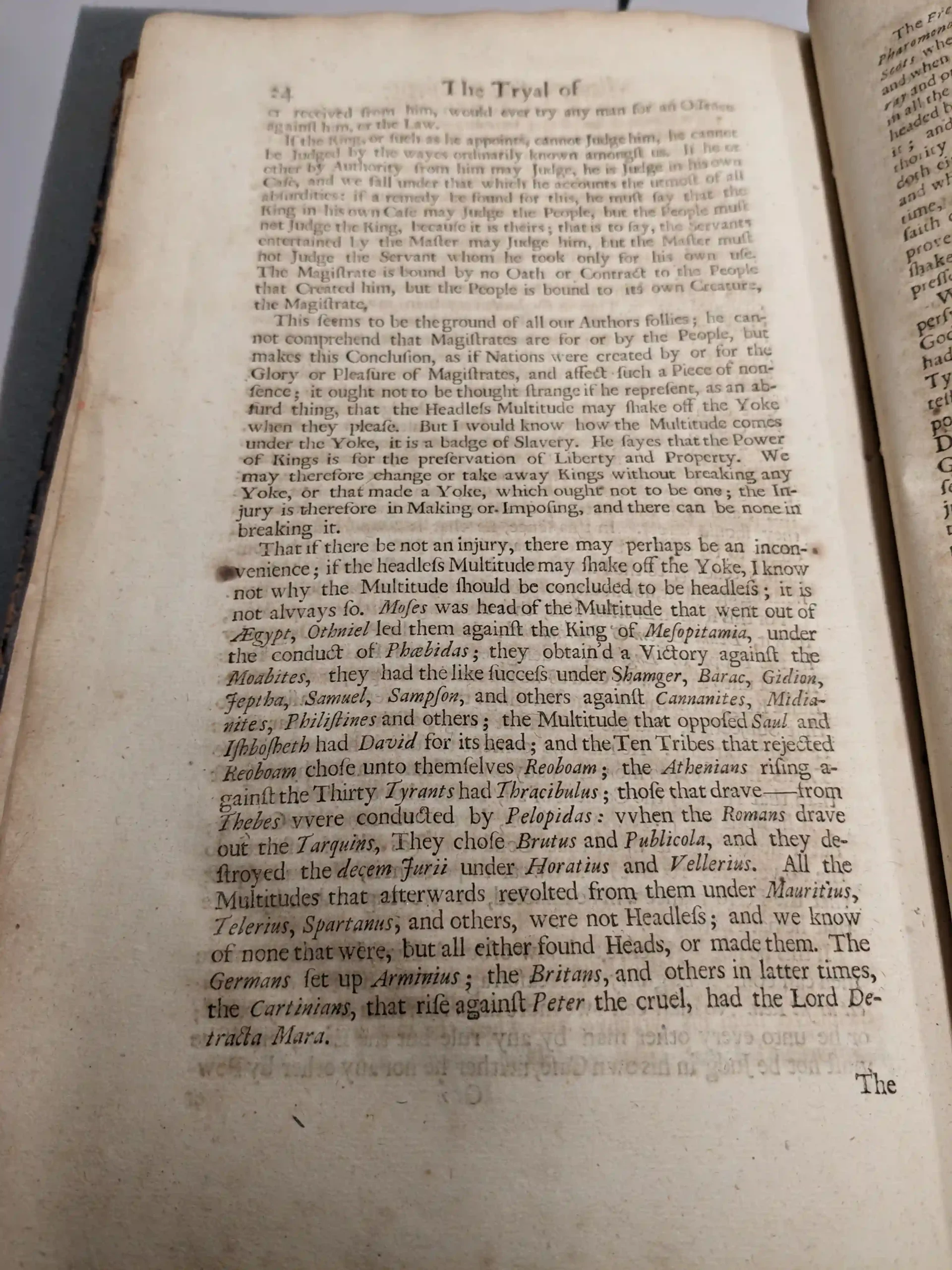

[24]

er received from him, would ever try any man for an Offence

against him, or the Law.

If the King, or such as he appoints, cannot Judge him, he cannot

be Judged by the wayes ordinarily known amongst us. If he or

other by Authority from him may Judge, he is Judge in his own

Case, and we fall under that which he accounts the utmost of all

absurdities: if a remedy be found for this, he must say that the

King in his own Case may Judge the People, but the People must

not Judge the King, because it is theirs; that is to say, the Servants

entertained by the Master may Judge him, but the Master must

not Judge the Servant whom he took only for his own use.

The Magistrate is bound by no Oath or Contract to the People

that Created him, but the People is bound to its own Creature,

the Magistrate.

This seems to be the ground of all our Authors follies; he can-

not comprehend that Magistrates are for or by the People, but

makes this Conclusion, as if Nations were created by or for the

Glory or Pleasure of Magistrates, and affect such a Piece of non-

sence; it ought not to be thought strange if he represent, as an ab-

surd thing, that the Headless Multitude may shake off the Yoke

when they please. But I would know how the Multitude comes

under the Yoke, it is a badge of Slavery. He sayes that the Power

of Kings is for the preservation of Liberty and Property. We

may therefore change or take away Kings without breaking any

Yoke, or that made a Yoke, which ought not to be one; the In-

jury is therefore in Making or Imposing, and there can be none in

breaking it.

That if there be not an injury, there may perhaps be an incon-

venience; if the headless Multitude may shake off the Yoke, I know

not why the Multitude should be concluded to be headless; it is

not always so. Moses was head of the Multitude that went out of

Ægypt, Othniel led them against the King of Mesopitamia, under

the conduct of Phœbidas; they obtain’d a Victory against the

Moabites, they had the like success under Shamger, Barac, Gidion,

Jeptha, Samuel, Sampson, and others against Cannanites, Midia-

nites, Philistines and others; the Multitude that opposed Saul and

Ishbosheth had David for its head; and the Ten Tribes that rejected

Reoboam chose unto themselves Reoboam; the Athenians rising a-

gainst the Thirty Tyrants had Thracibulus; those that drave – from

Thebes were conducted by Pelopidas: when the Romans drave

out the Tarquins, They chose Brutus and Publicola, and they de-

stroyed the decem Jurii under Horatius and Vellerius. All the

Multitudes that afterwards revolted from them under Mauritius,

Telerius, Spartanus, and others, were not Headless; and we know

of none that were, but all either found Heads, or made them. The

Germans set up Arminius; the Britans, and others in latter times,

the Cartinians, that rise against Peter the cruel, had the Lord De-

tracta Mara.

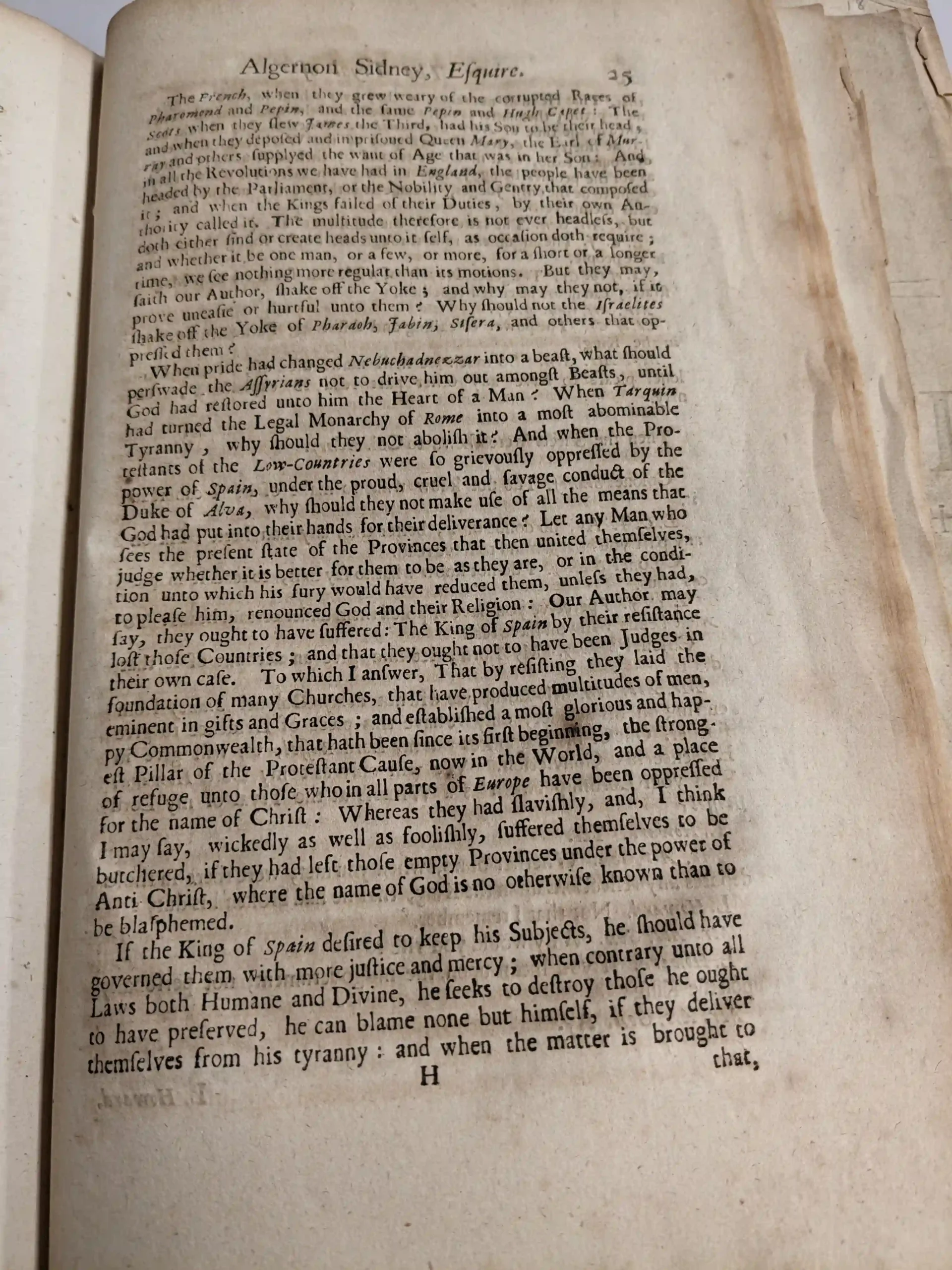

[25]

The French, when they grew weary of the corrupted Races of

Pharomond and Pepin, and the same Pepin and Hugh Capet: The

Scots when they slew James the Third, had his Son to be their head;

and when they deposed and imprisoned Queen Mary, the Earl of Mur-

-ray and others supplyed the want of Age that was in her Son: And

in all the Revolutions we have had in England, the people have been

headed by the Parliament, or the Nobility and Gentry that composed

it; and when the Kings failed of their Duties, by their own Au-

thority called it. The multitude therefore is not ever headless, but

doth either find or create heads unto it self, as occasion doth require;

and whether it be one man, or a few, or more, for a short or a longer

time, we see nothing more regular than its motions. But they may,

saith our Author, shake off the Yoke; and why may they not, if it

prove uneasie or hurtful unto them? Why should not the Israelites

shake off the Yoke of Pharaoh, Jabin, Sifera, and others that op-

pressed them?

When pride had changed Nebuchadnezzar into a beast, what should

perswade the Assyrians not to drive him out amongst Beasts, until

God had restored unto him the Heart of a Man? When Tarquin

had turned the Legal Monarchy of Rome into a most abominable

Tyranny, why should they not abolish it? And when the Pro-

testants of the Low-Countries were so grievously oppressed by the

power of Spain, under the proud, cruel and savage conduct of the

Duke of Alva, why should they not make use of all the means that

God had put into their hands for their deliverance? Let any Man who

sees the present state of the Provinces that then united themselves,

judge whether it is better for them to be as they are, or in the condi-

tion unto which his fury would have reduced them, unless they had,

to please him, renounced God and their Religion: Our Author may

say, they ought to have suffered: The King of Spain by their resistance

lost those Countries; and that they ought not to have been Judges in

their own case. To which I answer, That by resisting they laid the

foundation of many Churches, that have produced multitudes of men,

eminent in gifts and Graces; and established a most glorious and hap-

py Commonwealth, that hath been since its first beginning, the strong-

est Pillar of the Protestant Cause, now in the World, and a place

of refuge unto those who in all parts of Europe have been oppressed

for the name of Christ: Whereas they had slavishly, and, I think

I may say, wickedly as well as foolishly, suffered themselves to be

butchered, if they had left those empty Provinces under the power of

Anti Christ, where the name of God is no otherwise known than to

be blasphemed.

If the King of Spain desired to keep his Subjects, he should have

governed them with more justice and mercy; when contrary unto all

Laws both Humane and Divine, he seeks to destroy those he ought

to have preserved, he can blame none but himself, if they deliver

themselves from his tyranny: and when the matter is brought to

[26]

that, That He must not reign, or they over whom he would reign,

must perish; the matter is easily decided, as if the question had been

asked in the time of Nero or Domitian, Whether they should be

left at liberty to destroy the best part of the World, as they en-

deavoured to do, or it should be rescued by their destruction? And

as for the peoples being Judges in their own case, it is plain, they

ought to be the only Judges, because it is their own, and only con-

cerns themselves.

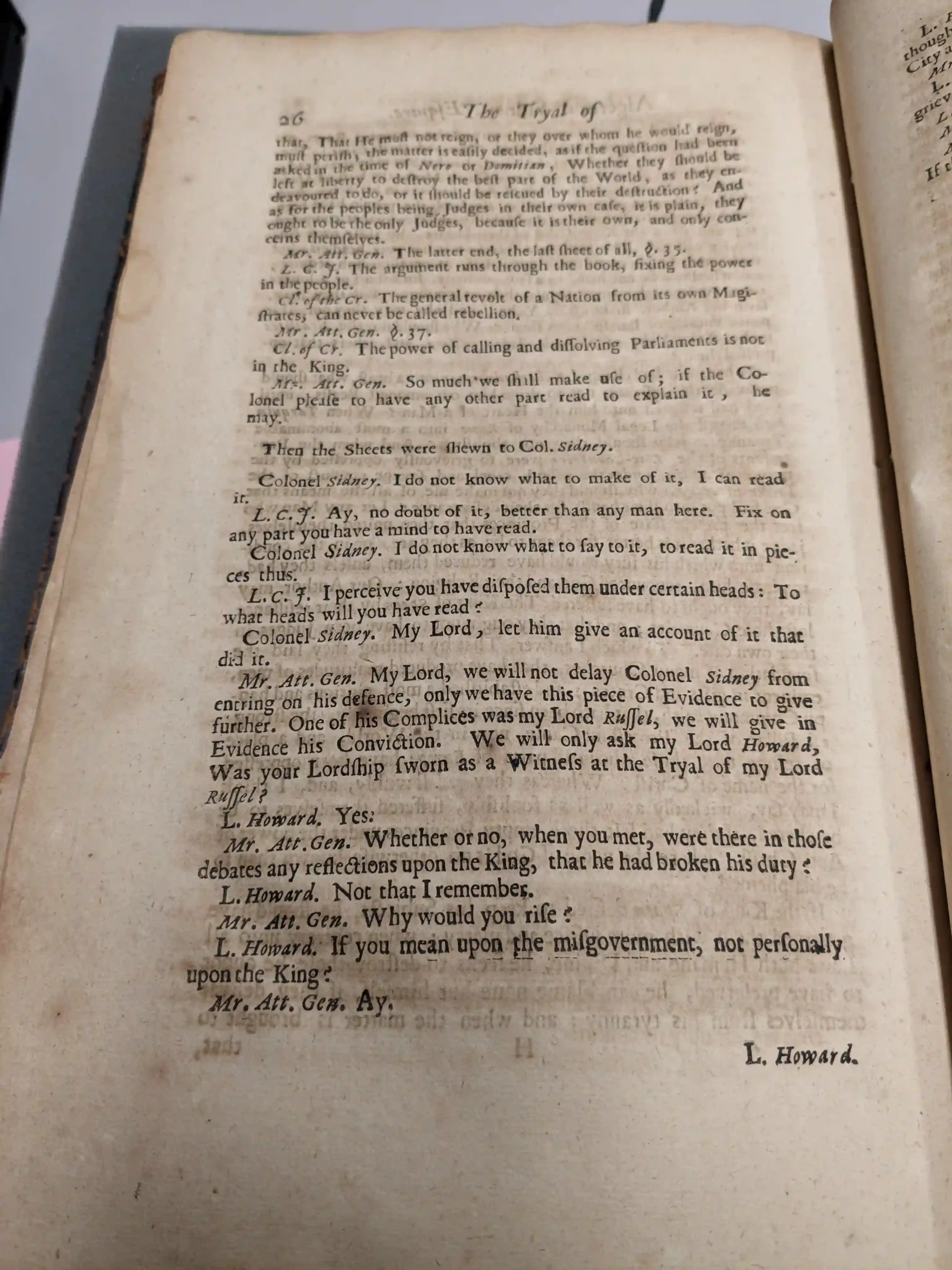

Mr. Att. Gen. The latter end, the last sheet of all, §. 35.

L. C. J. The argument runs through the book, fixing the power

in the people.

Cl. of the Cr. The general revolt of a Nation from its own Magi-

strates, can never be called rebellion

Mr. Att. Gen. §. 37.

Cl. of the Cr. The power of calling and dissolving Parliament is not

in the King.

Mr. Att. Gen. So much we shall make use of; if the Co-

lonel please to have any other part read to explain it, he

may.

Then the Sheets were shewn to Col. Sidney.

Colonel Sidney. I do not know what to make of it, I can read

it.

L. C. J. Ay, no dobut of it, better than any man here. Fix on

any part you have a mind to have read.

Colonel Sidney. I do not know what to say to it, to read it in pie-

ces thus.

L. C. J. I perceive you have disposed them under certain heads: To

what heads will you have read?

Colonel Sidney. My Lord, let him give an account of it that

did it.

Mr. Att. Gen. My Lord, we will not delay Colonel Sidney from

entring on his defence, only we have this piece of Evidence to give

further. One of his Complices was my Lord Russel, we will give in

Evidence his Conviction. We will only ask my Lord Howard,

Was your Lordship sworn as a Witness at the Tryal of my Lord

Russel?

L. Howard. Yes.

Mr. Att. Gen. Whether or no, when you met, were there in those

debates any reflections upon the King, that he had broken his duty?

L. Howard. Not that I remember.

Mr. Att. Gen. Why would you rise?

L. Howard. If you mean upon the misgovernment, not personally

upon the King?

Mr. Att. Gen. Ay.

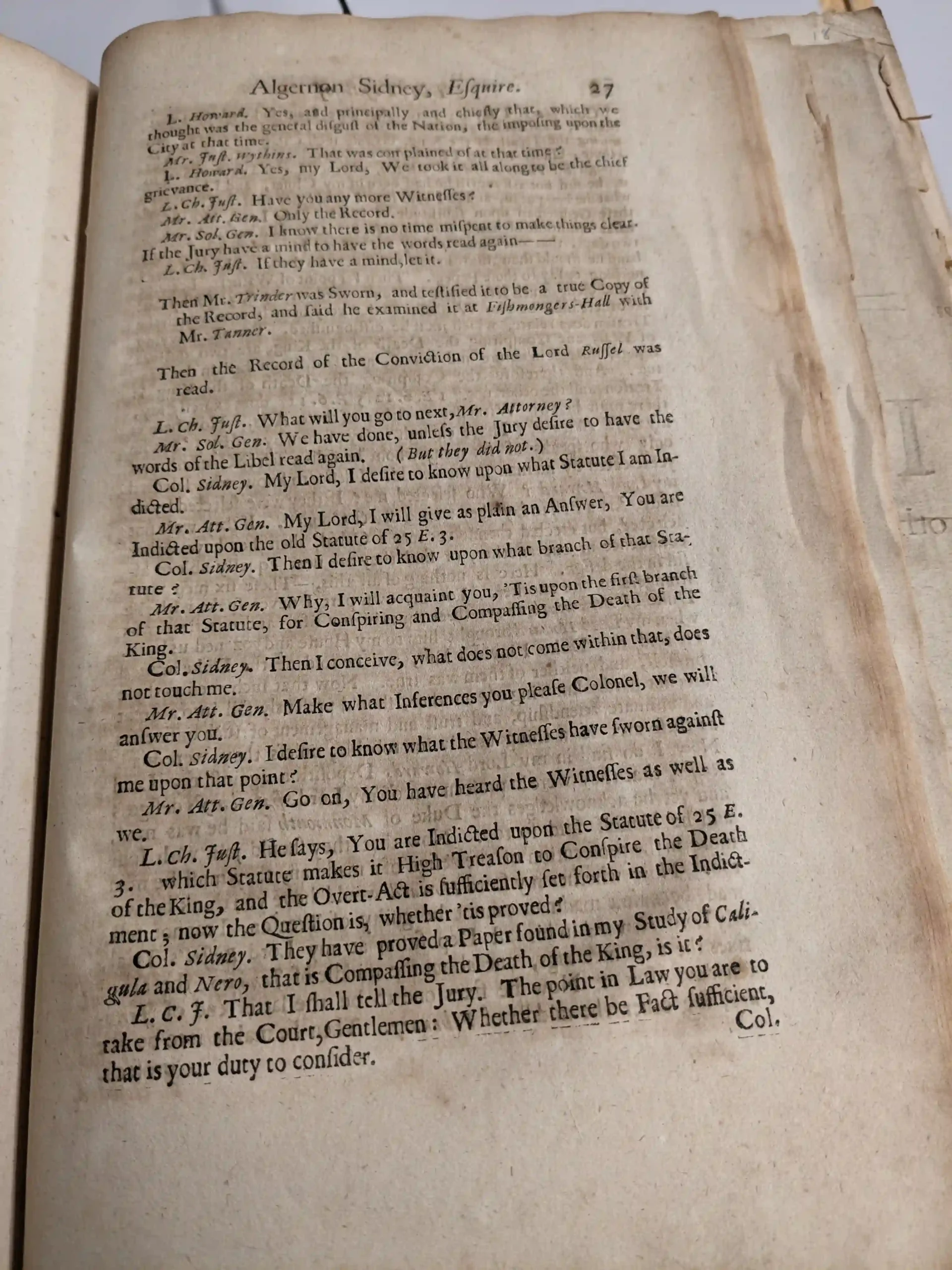

[27]

L. Howard. Yes, and principally and chiefly that, which we

thought was the general disgust of the Nation, the imposing upon the

City at that time.

Mr. Just. Wythins. That was complained of at that time?

L. Howard. Yes, my Lord. We took it all along to be the chief

grievance.

L. Ch. Just. Have you any more Witnesses?

Mr. Att. Gen. Only the Record.

Mr. Sol. Gen. I know there is no time mispent to make things clear.

If the Jury have a mind to have the words read again – –

L. Ch. Just. If they have a mind, let it.

Then Mr. Trinder was Sworn, and testified it to be a true Copy of

the Record, and said he examined it at Fishmongers-Hall with

Mr. Tanner.

Then the Record of the Conviction of the Lord Russel was

read.

L. Ch. Just. What will you go to next, Mr. Attorney?

Mr. Sol. Gen. We have done, unless the Jury desire to have the

words of the Libel read again. (But they did not.)

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I desire to know upon what Statute I am In-

dicted.

Mr. Att. Gen. My Lord, I will give as plain an Answer, You are

Indicted upon the old Statute of 25 E. 3.

Col. Sidney. Then I desire to know upon what branch of that Sta-

tute?

Mr. Att. Gen. Why, I will acquaint you, ‘Tis upon the first branch

of that Statute, for Conspiring and Compassing the Death of the

King.

Col. Sidney. Then I conceive, what does not come within that, does

not touch me.

Mr. Att. Gen. Make what Inferences you please Colonel, we will

answer you.

Col. Sidney. I desire to know what the Witnesses have sworn against

me upon that point?

Mr. Att. Gen. Go on, You have heard the Witnesses as well as

we.

L. Ch. Just. He says, You are indicted upon the Statute of 25 E.

3. which Statute makes it High Treason to Conspire the Death

of the King, and the Overt-Act is sufficiently set forth in the Indict-

ment; now the Question is, whether ’tis proved?

Col. Sidney. They have proved a Paper found in my Study of Cali-

gula and Nero, that is Compassing the Death of the King, is it?

L. C. J. That I shall tell the Jury. The point in Law you are to

take from the Court, Gentlemen: Whether there be Fact sufficient,

that is your duty to consider.

[28]

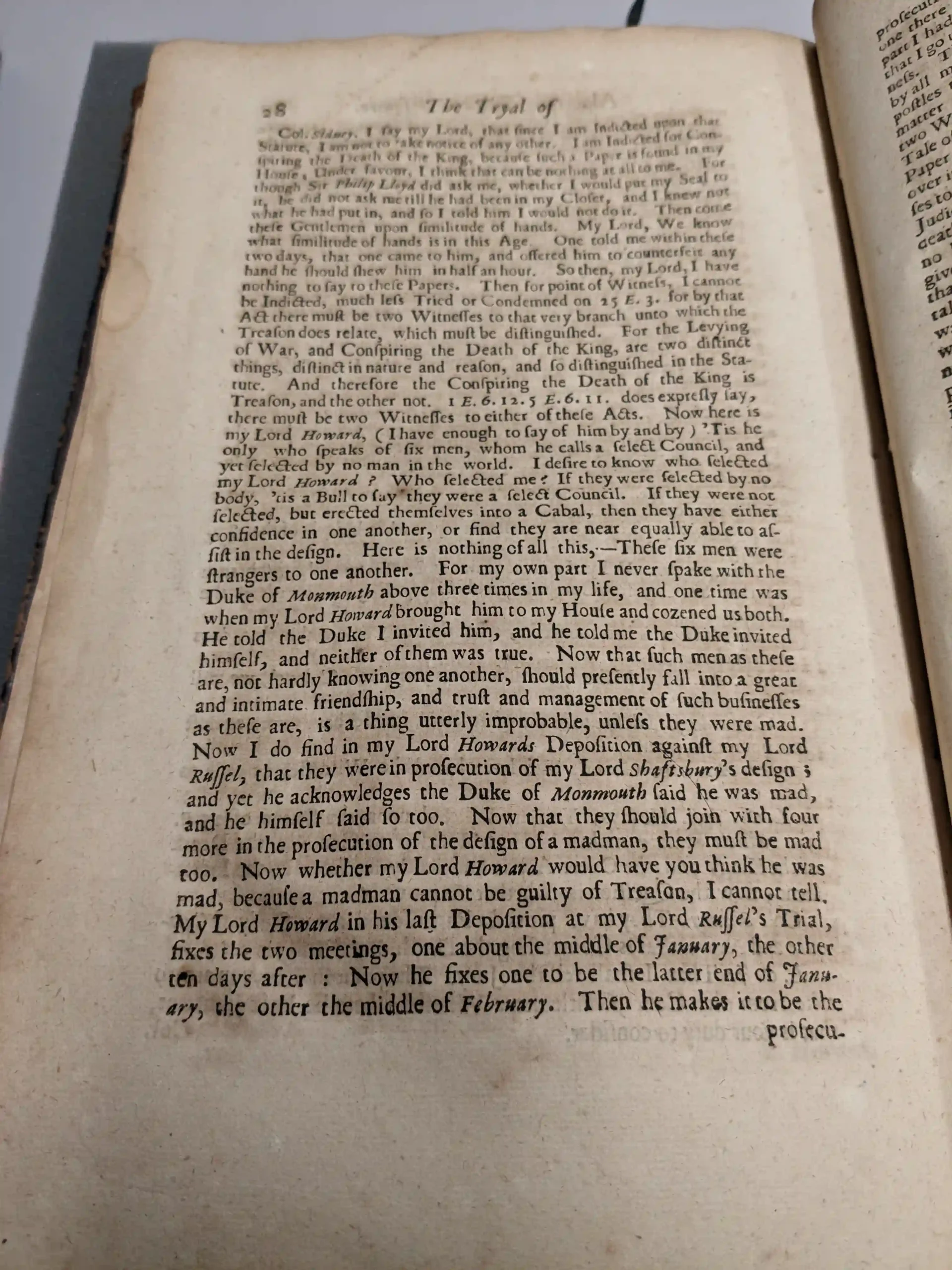

Col. Sidney. I say my Lord, that since I am Indicted upon that

Statute, I am not to take notice of any other. I am Indicted for Con-

spiring the Death of the King, because such a Paper is found in my

House; Under favour, I think that can be nothing at all to me. For

though Sir Philip Lloyd did ask me, whether I would put my Seal to

it, he did not ask me till he had been in my Closet, and I knew not

what he had put in, and so I told him I would not do it. Then come

these Gentlemen upon similitude of hands. My Lord, We know

what similitude of hands is in this Age. One told me within these

two days, that one came to him, and offered him to counterfeit any

hand he should shew him in half an hour. So then, my Lord, I have

nothing to say to these Papers. Then for point of Witness, I cannot

be Indicted, much less Tried or Condemned on 25 E. 3. for by that

Act there must be two Witnesses to that very branch unto which the

Treason does relate, which must be distinguished. For the Levying

of War, and Conspiring the Death of the King, are two distinct

things, distinct in nature and reason, and so distinguished in the Sta-

tute. And therefore the Conspiring the Death of the King is

Treason, and the other not. 1 E. 6. 12. 5. E. 6. II. does expressly say,

there must be two Witnesses to either of these Acts. Now here is

my Lord Howard, (I have enough to say of him by and by) ‘Tis he

only who speaks of six men, whom he calls a select Council, and

yet selected by no man in the world. I desire to know who selected

my Lord Howard? Who selected me? If they were selected by no

body, ’tis a Bull to say they were a select Council. If they were not

selected, but erected themselves into a Cabal, then they have either

confidence in one another, or find they are near equally able to as-

sist in the design. Here is nothing of all this, — These six men were

strangers to one another. For my own part I never spake with the

Duke of Monmouth above three times in my life, and one time was

when my Lord Howard brought him to my House and cozened us both.

He told the Duke I invited him, and he told me the Duke invited

himself, and neither of them was true. Now that such men as these

are, not hardly knowing one another, should presently fall into a great

and intimate friendship, and trust and management of such businesses

as these are, is a thing utterly improbable, unless they were mad.

Now I do find in my Lord Howards Deposition against my Lord

Russel, that they were in prosecution of my Lord Shaftsbury‘s design;

and yet he acknowledges the Duke of Monmouth said he was mad,

and he himself said so too. Now that they should join with four

more in the prosecution of the design of a madman, they must be mad

too. Now whether my Lord Howard would have you think he was

mad, because a madman cannot be guilty of Treason, I cannot tell.

My Lord Howard in his last Deposition at my Lord Russel‘s Trial,

fixes the two meetings, one about the middle of January, the other

ten days after: Now he fixes one to the latter end of Janu-

ary, the other the middle of February. Then he makes it to be the

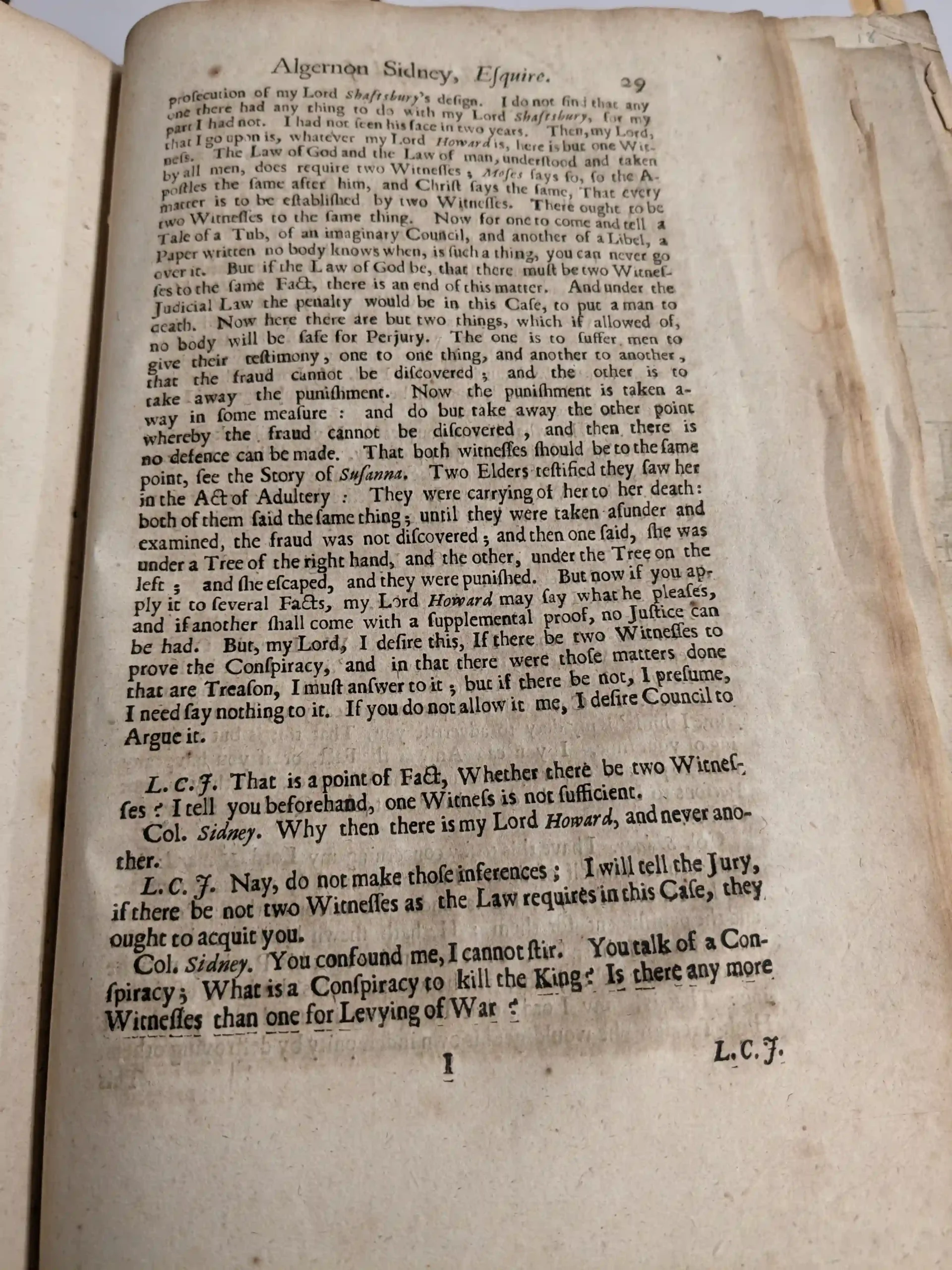

[29]

prosecution of my Lord Shaftsbury‘s design. I do not find that any

one there had any thing to do with my Lord Shaftsbury, for my

part I had not. I had not seen his face in two years. Then, my Lord,

that I go upon is, whatever my Lord Howard is, here is but one Wit-

ness. The Law of God and the Law of man, understood and taken

by all men, does require two Witnesses; Moses says so, so the A-

postles the same after him, and Christ says the same, That every

matter is to be established by two Witnesses. There ought to be

two Witnesses to the same thing. Now for one to come and tell a

Tale of a Tub, of an imaginary Council, and another of a Libel, a

Paper written no body knows when, is such a thing, you can never go

over it. But if the Law of God be, that there must be two Witnes-

ses to the same Fact, there is an end of this matter. And under the

Judicial Law the penalty would be in this Case, to put a man to

death. Now here there are but two things, which if allowed of,

no body will be safe for Perjury. The one is to suffer men to

give their testimony, one to one thing, and another to another,

that the fraud cannot be discovered; and the other is to

take away the punishment. Now the punishment is taken a-

way in some measure: and do but take away the other point

whereby the fraud cannot be discovered, and then there is

no defence can be made. That both witnesses should be to the same

point, see the Story of Susanna. Two Elders testified they saw her

in the Act of Adultery: They were carrying of her to her death:

both of them said the same thing; until they were taken asunder and

examined, the fraud was not discovered; and then one said, she was

under a Tree of the right hand, and the other, under the Tree on the

left; and she escaped, and they were punished. But now if you ap-

ply it to several Facts, my Lord Howard may say what he pleases,

and if another shall come with a supplemental proof, no Justice can

be had. But, my Lord, I desire this, If there be two Witnesses to

prove the Conspiracy, and in that there were those matters done

that are Treason, I must answer to it; but if there be not, I presume,

I need say nothing to it. If you do not allow it me, I desire Council to

Argue it.

L. C. J. That is a point of Fact, Whether there be two Witnes-

ses? I tell you beforehand, one Witness is not sufficient.

Col. Sidney. Why then there is my Lord Howard, and never ano-

ther.

L. C. J. Nay, do not make those inferences; I will tell the Jury,

if there be not two Witnesses as the Law requires in this Case, they

ought to acquit you.

Col. Sidney. You confound me, I cannot stir. You talk of a Con-

spiracy; What is a Conspiracy to kill the King? Is there any more

Witnesses than one for Levying of War?

[30]

L. C. J. Pray do not deceive your self; You must not think the

Court and you intend to enter into a Dialogue. Answer to the Fact;

if there be not sufficient Fact, the Jury will acquit you. Make what

Answer you can to it.

Col. Sidney. Then I say, There being but one Witness, I am not to

Answer to it at all.

L. C. J. If you rely upon that, we will direct the Jury presently.

Col. Sidney. Then for Levying War, what does any one say?

My Lord Howard, let him if he please, reconcile what he hath said

now, with what he said at my Lord Russel‘s Trial. There he said, he

said all he could; and now he has got I do not know how many things

that were never spoken of there. I appeal to the Court whether he

did then speak one word of that, that he now says of Mr. Hambden.

He sets forth his Evidence very Rhetorically, but it does not

become a Witness, for he is only to tell what is done and said;

but he does not tell what was done and said. He says they

took upon them to consider, but does not say what one man said, or

what one man resolved, much less what I did. My Lord, If these things

are not to be distinguished, but shall be jumbled all up together, I con-

fess I do not know what to say.

L. C. J. Take what liberty you please. If you will make no De-

fence, then we will direct the Jury presently. We will direct them in

the Law, and recollect matter of Fact as well as we can.

Col. Sidney. Why then my Lord, I desire the Law may be reserv-

ed to me, I desire I may have Council to that point of there being but

one Witness.

L. C. J. That is point of Fact. If you can give any testimony to

disparage the Witness, do it.

Col. Sidney. I have a great deal to that.

L. C. J. Go on to it then.

Col. Sidney. Then, my Lord, was there a War Levyed? Or was it

prevented? Why then, if it be prevented, ’tis not Levyed; if it be

not Levyed, ’tis not within the Statute; so this is nothing to me.

L. C. J. The Court will have patience to hear you; but at the same

time I think ’tis my duty to advertise you, That this is but mispend-

ing of your time. If you Answer the Fact, or if you have any

mind to put any disparagement upon the Witnesses, that they are not

Persons to be believed, do it, but do not ask us Questions this way or

t’other.

Col. Sidney. I have this to say concerning my Lord Howard: He

hath accused himself of divers Treasons, and I do not hear that he

has his Pardon of any: He is under the terror of those Treasons,

and the punishment for them: He hath shewn himself to be under

that terror: He hath said, That he could not get his Pardon, until he

had done some other jobbs, till he was past this drudgery of swear-

ing: That is, my Lord, that he having incurred the penalty of

High-Treason, he would get his own indempnity by destroying others.

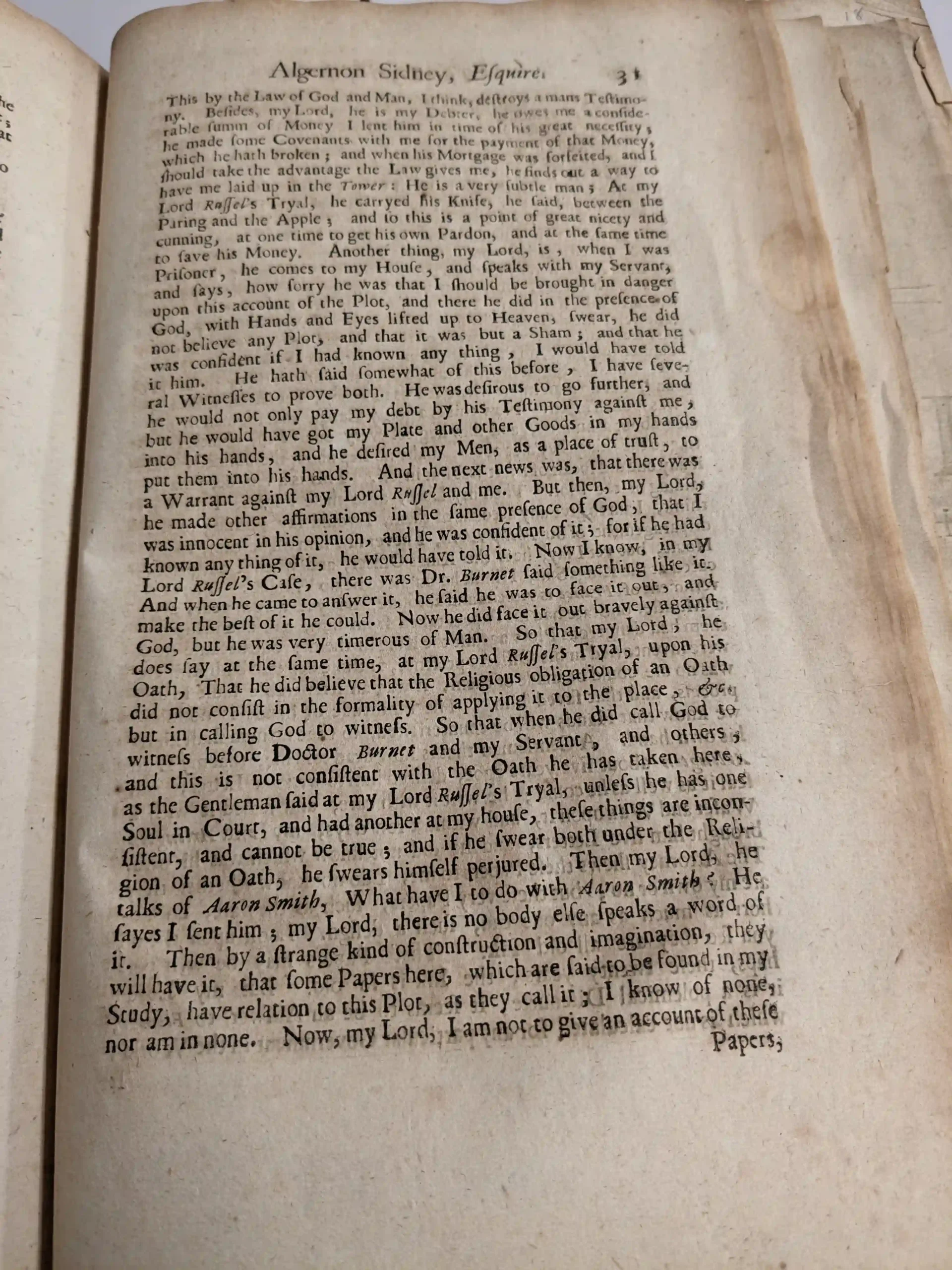

[31]

This by the Law of God and Man, I think, destroys a mans Testimo-

ny. Besides, my Lord, he is my Debter, he owes me a conside-

rable summ of Money I lent him in time of his great necessity;

he made some Covenants with me for the payment of that Money,

which he hath broken; and when his Mortgage was forfeited, and I

should take the advantage the Law gives me, he finds out a way to

have me laid up in the Tower: He is a very subtle man; At my

Lord Russel‘s Tryal, he carryed his Knife, he said, between the

Paring and the Apple; and to this is a point of great nicety and

cunning, at one time to get his own Pardon, and at the same time

to save his Money. Another thing, my Lord, is, when I was

Prisoner, he comes to my House, and speaks with my Servant,

and says, how sorry he was that I should be brought in danger

upon this account of the Plot, and there he did in the presence of

God, with Hands and Eyes lifted up to Heaven, swear, he did

not believe any Plot, and that it was but a Sham; and that he

was confident if I had known any thing, I would have told

it him. He hath said somewhat of this before, I have seve-

ral Witnesses to prove both. He was desirous to go further, and

he would not only pay my debt by his Testimony against me,

but he would have got my Plate and other Goods in my hands

into his hands, and he desired my Men, as a place of trust, to

put them into his hands. And the next news was, that there was

a Warrant against my Lord Russel and me. But then, my Lord,

he made other affirmations in the same presence of God, that I

was innocent in his opinion, and he was confident of it; for if he had

known any thing of it, he would have told it. Now I know, in my

Lord Russel‘s Case, there was Dr. Burnet said something like it.

And when he came to answer it, he said he was to face it out, and

make the best of it he could. Now he did face it out bravely against

God, but he was very timerous of Man. So that my Lord, he

does say at the same time, at my Lord Russel‘s Tryal, upon his

Oath, That he did believe that the Religious obligation of an Oath

did not consist in the formality of applying it to the place, &c.

but in calling God to witness. So that when he did call God to

witness before Doctor Burnet and my Servant, and others,

and this is not consistent with the Oath he has taken here,

as the Gentleman said at my Lord Russel‘s Tryal, unless he has one

Soul in Court, and had another at my house, these things are incon-

sistent, and cannot be true; and if he swear both under the Reli-

gion of an Oath, he swears himself perjured. Then my Lord, he

talks of Aaron Smith, What have I to do with Aaron Smith? He

sayes I sent him; my Lord, there is no body else speaks a word of

it. Then by a strange kind of construction and imagination, they

will have it, that some Papers here, which are said to be found in my

Study, have relation to this Plot, as they call it; I know of none,

nor am in none. Now, my Lord, I am not to give an account of these

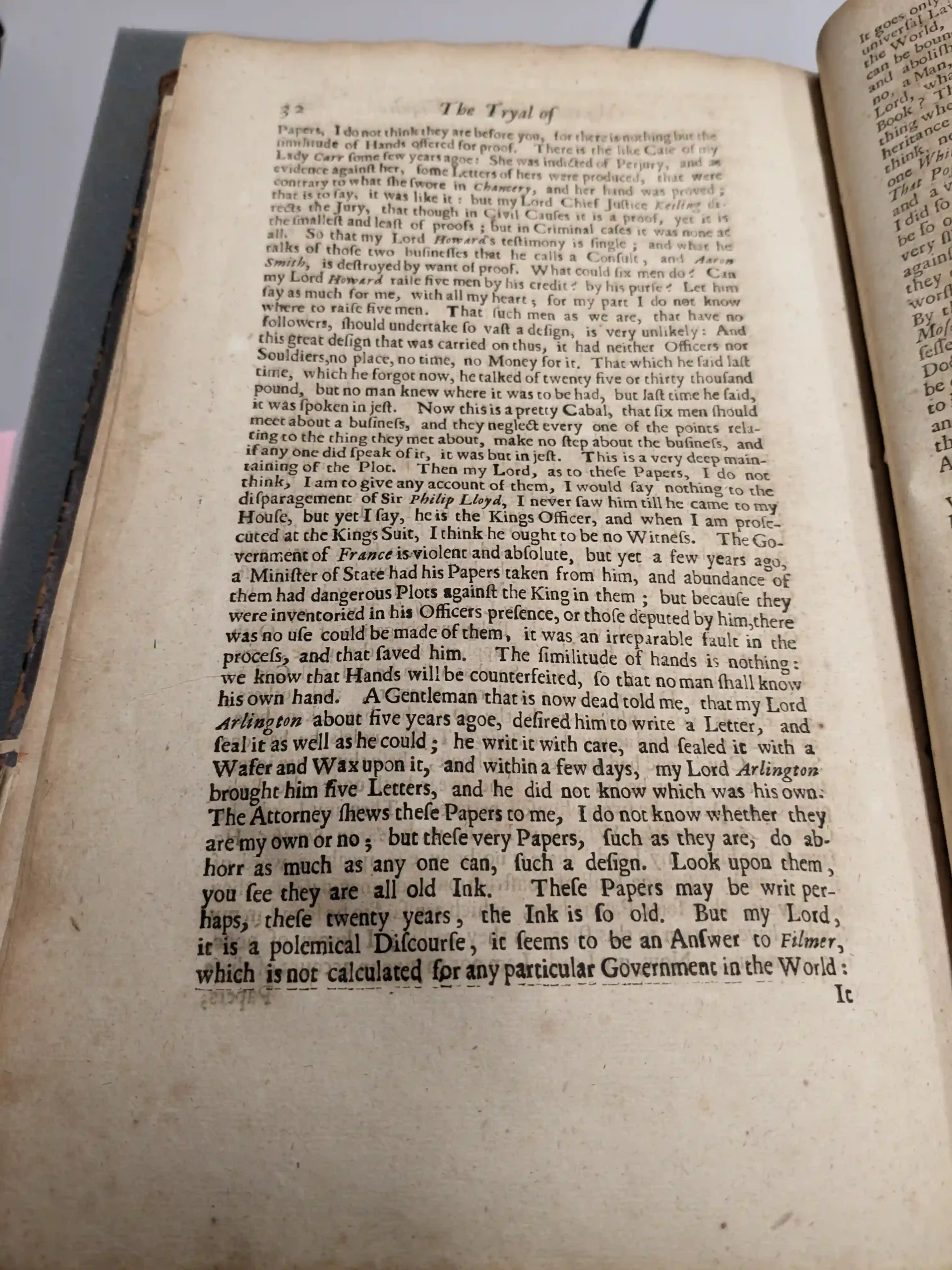

[32]

Papers, I do not think they are before you, for there is nothing but the

similitude of Hands offered for proof. There is the like Case of my

Lady Carr some few years agoe: She was indicted of Perjury, and as

evidence against her, some Letters of hers were produced, that were

contrary to what she swore in Chancery, and her hand was proved;

that is to say, it was like it: but my Lord Chief Justice Keiling di-

rects the Jury, that though in Civil Causes it is a proof, yet it is

the smallest and least of proofs; but in Criminal cases it was none at

all. So that my Lord Howard‘s testimony is single; and what he

talks of these two businesses that he calls a Consult; and Aaron

Smith, is destroyed by want of proof. What could six men do? Can

my Lord Howard raise five men by his credit? by his purse? Let him

say as much for me, with all my heart; for my part I do not know

where to raise five men. That such men as we are, that have no

followers, should undertake so vast a design, is very unlikely: And

this great design that was carried on thus, it had neither Officers nor

Souldiers, no place, no time, no Money for it. That which he said last

time, which he forgot now, he talked of twenty five or thirty thousand

pound, but no man knew where it was to be had, but last time he said,

it was spoken in jest. Now this is a pretty Cabal, that six men should

meet about a business, and they neglect every one of the points rela-

ting to the thing they met about, make no step about the business, and

if any one did speak of it, it was but in jest. This is a very deep main-

taining of the Plot. Then my Lord, as to these Papers, I do not

think, I am to give any account of them, I would say nothing to the

disparagement of Sir Philip Lloyd, I never saw him till he came to my

House, but yet I say, he is the Kings Officer, and when I am prose-

cuted at the Kings Suit, I think he ought to be no Witness. The Go-

vernment of France is violent and absolute, but yet a few years ago,

a Minister of State had his Papers taken from him, and abundance of

them had dangerous Plots against the King in them; but because they

were inventoried in his Officers presence, or those deputed by him, there

was no use could be made of them, it was an irreparable fault in the

process, and that saved him. The similitude of hands is nothing:

we know that Hands will be counterfeited, so that no man shall know

his own hand. A Gentleman that is now dead told me, that my Lord

Arlington about five years agoe, desired him to write a Letter, and

seal it as well as he could; he writ it with care, and sealed it with a

Wafer and Wax upon it, and within a few days, my Lord Arlington

brought him five Letters, and he did not know which was his own.

The Attorney shews these Papers to me, I do not know whether they

are my own or no; but these very Papers, such as they are, do ab-

horr as much as any one can, such a design. Look upon them,

you see they are all old Ink. These Papers may be writ per-

haps, these twenty years, the Ink is so old. But my Lord,

it is a polemical Discourse, it seems to be an Answer to Filmer,

which is not calculated for any particular Government in the World:

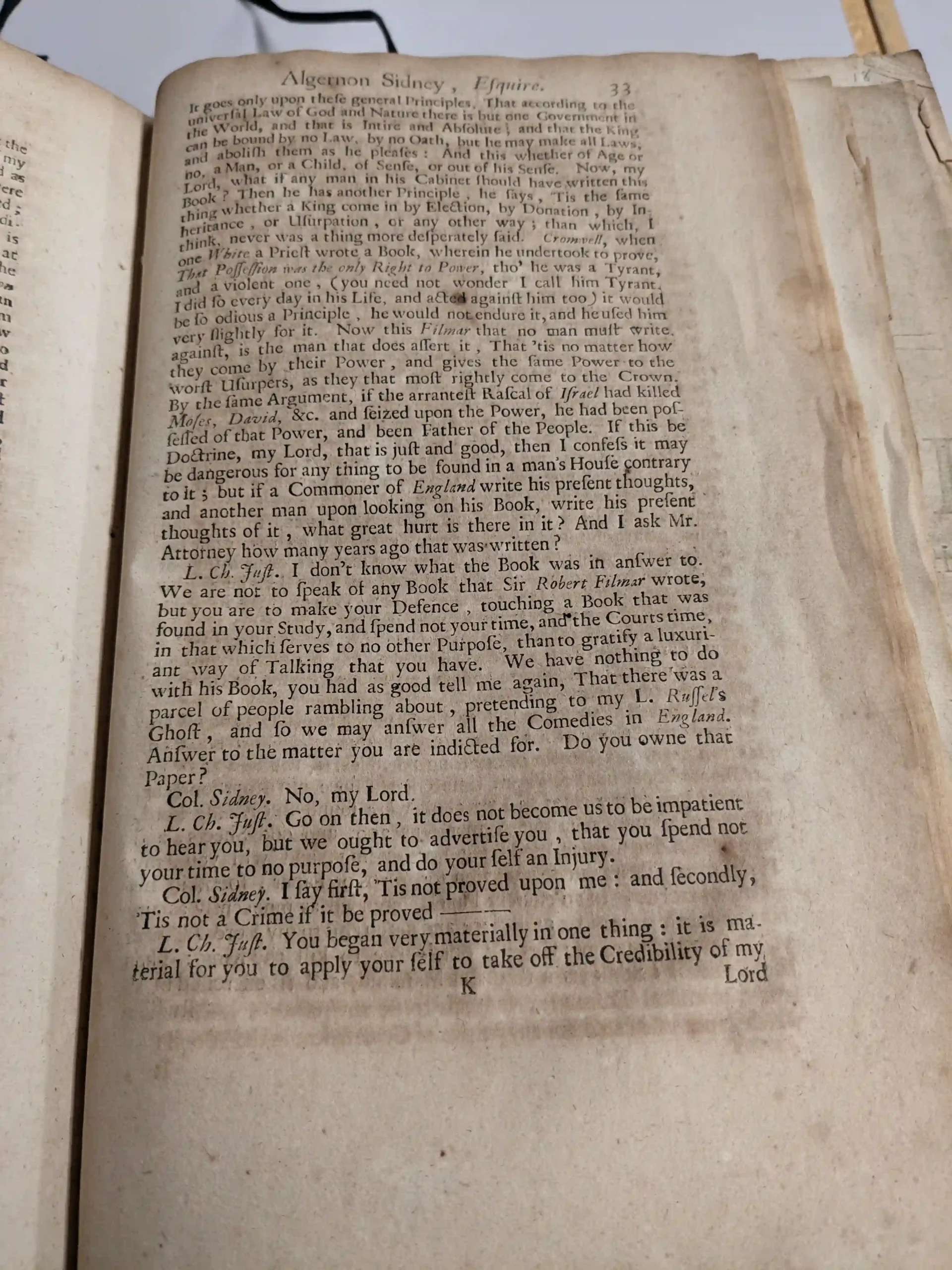

[33]

It goes only upon these general Principles, That according to the

universal Law of God and Nature there is but one Government in

the World, and that is Intire and Absolute; and that the King

can be bound by no Law, by no Oath, but he may make all Laws,

and abolish them as he pleases: And this whether of Age or

no, a Man, or a Child, of Sense, or out of his Sense. Now, my

Lord, what if any man in his Cabinet should have written this

Book? Then he has another Principle, he says, ‘Tis the same

thing whether a King come in by Election, by Donation, by In-

heritance, or Usurpation, or any other way; than which, I

think, never was a thing more desperately said. Cromwell, when

one White a Priest wrote a Book, wherein he undertook to prove,

That Possession was the only Right to Power, tho’ he was a Tyrant,

and a violent one, (you need not wonder I call him Tyrant.

I did so every day in his Life, and acted against him too) it would

be so odious a Principle, he would not endure it, and he used him

very slightly for it. Now this Filmar that no man must write

against, is the man that does assert it, That ’tis no matter how

they come by their Power, and gives the same Power to the

worst Usurpers, as they that most rightly come to the Crown.

By the same Argument, if the arrantest Rascal of Israel had killed

Moses, David, &c. and seized upon their Power, he had been pos-

sessed of that Power, and been Father of the People. If this be

Doctrine, my Lord, that is just and good, then I confess it may

be dangerous for any thing to be found in a man’s House contrary

to it; but if a Commoner of England write his present thoughts,

and another man upon looking on his Book, write his present

thoughts of it, what great hurt is there in it? And I ask Mr.

Attorney how many years ago that was written?

L. Ch. Just. I don’t know what the Book was in answer to.

We are not to speak of any Book that Sir Robert Filmar wrote,

but you are to make your Defence, touching a Book that was

found in your Study, and spend not your time, and the Courts time,

in that which serves to no other Purpose, than to gratify a luxuri-

ant way of Talking that you have. We have nothing to do

with his Book, you had as good tell me again, That there was a

parcel of people rambling about, pretending to my L. Russel‘s

Ghost, and so we may answer all the Comedies in England.

Answer to the matter you are indicted for. Do you owne that

Paper?

Col. Sidney. No, my Lord.

L. Ch. Just. Go on then, it does not become us to be impatient

to hear you, but we ought to advertise you, that you spend not

your time to no purpose, and do your self an Injury.

Col. Sidney. I say first, ‘Tis not proved upon me: and secondly,

‘Tis not a Crime it be proved —

L. Ch. Just. You began very materially in one thing: it is ma-

terial for you to apply your self to take off the Credibility of my

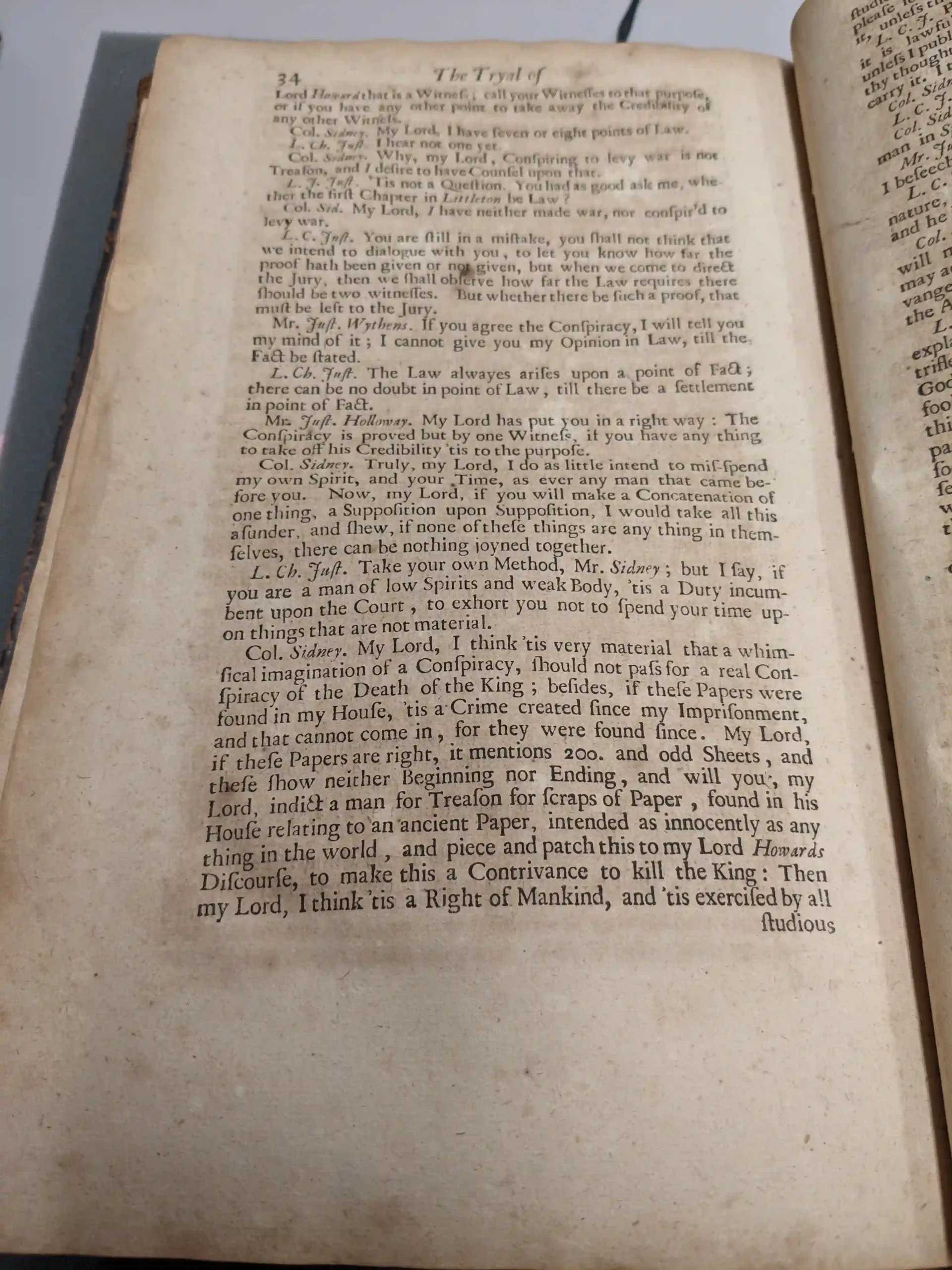

[34]

Lord Howard that is a Witness; call your Witnesses to that purpose,

or if you have any other point to take away the Credibility of

any other Witness.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I have seven or eight points of Law.

L. Ch. Just. I hear not one yet.

Col. Sidney. Why, my Lord, Conspiring to levy war is not

Treason, and I desire to have Counsel upon that.

L. J. Just. ‘Tis not a Question. You had as good ask me, whe-

ther the first Chapter in Littleton be Law?

Col. Sid. My Lord, I have neither made war, nor conspir’d to

levy war.

L. C. Just. You are still in a mistake, you shall not think that

we intend to dialogue with you, to let you know how far the

proof hath been given or not given, but when he come to direct

the Jury, then we shall observe how far the Law requires there

should be two witnesses. But whether there be such a proof, that

must be left to the Jury.

Mr. Just. Wythens. If you agree the Conspiracy, I will tell you

my mind of it; I cannot give you my Opinion in Law, till the

Fact be stated.

L. Ch. Just. The Law alwayes arises upon a point of Fact;

there can be no doubt in point of Law, till there be a settlement

in point of Fact.

Mr. Just. Holloway. My Lord has put you in a right way: The

Conspiracy is proved but by one Witness, if you have any thing

to take off his Credibility ’tis to the purpose.

Col. Sidney. Truly, my Lord, I do as little intend to mis-spend

my own Spirit, and your Time, as ever any man that came be-

fore you. Now, my Lord, if you will make a Concatenation of

one thing, a Supposition upon Supposition, I would take all this

asunder, and shew, if none of these things are any thing in them-

selves, there can be nothing joyned together.

L. Ch. Just. Take you own Method, Mr. Sidney; but I say, if

you are a man of low Spirits and weak Body, ’tis a Duty incum-

bent upon the Court, to exhort you not to spend your time up-

on things that are not material.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I think ’tis very material that a whim-

sical imagination of a Conspiracy, should not pass for a real Con-

spiracy of the Death of the King; besides, if these Papers were

found in my House, ’tis a Crime created since my Imprisonment,

and that cannot come in, for they were found since. My Lord,

if these Papers are right, it mentions 200. and odd Sheets, and

these show neither Beginning nor Ending, and will you, my

Lord, indict a man for Treason for scraps of Paper, found in his

House relating to an ancient Paper, intended as innocently as any

thing in the world, and piece and patch this to my Lord Howards

Discourse, to make this a Contrivance to kill the King: Then

my Lord, I think ’tis a Right of Mankind, and ’tis exercised by all

[35]

studious men, that they write in their own Closets what they

please for their own Memory, and no man can be answerable for

it, unless they publish it.

L. C. J. Pray don’t go away with that right of mankind, that

it is lawful for me to write what I will in my own Closet,

unless I publish it; I have been told, Curse not the King, not in

thy thoughts, not in thy Bed-Chamber, the Birds of the air will

carry it. I took it to be the duty of mankind, to observe that.

Col. Sidney. I have lived under the Inquisition —-

L. C. J. God be thanked, we are governed by Law.

Col. Sidney. I have lived under the Inquisition, and there is no

man in Spain can be tryed for Heresie —-

Mr. Just. Withins. Draw no Presidents from the Inquisition, here,

I beseech you Sir.

L. C. J. We must not endure men to talk, that by the right of

nature, every man may contrive mischief in his own Chamber,

and he is not to be punished, till he thinks fit to be called to it.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, if you will take Scripture by pieces, you

will make all the Penmen of the Scripture blasphemous; you

may accuse David of saying, There is no God; and accuse the E-

vangelists, of saying, Christ was a Blasphemer and a Seducer; and

the Apostles, That they were drunk.

L. C. J. Look you, Mr. Sidney, if there be any part of it, that

explain the sense of it, you shall have it read; indeed we are

trifled with a little. ‘Tis true, in Scripture ’tis said, there is no

God, and you must not take that alone, but you must say, the

fool hath said in his heart, there is no God. Now here is a

thing imputed to you in the Libel; if you can say, there is any

part that is in excuse of it, call for it. As for the purpose, who

soever does publish, that the King may be put in chains or depo-

sed, is a Traytor; but whosoever says, that none but Traytors

would put the King in Chains or depose him, is an honest man;

therefore apply ad idem, but don’t let us make Excursions.

Col. Sidney. If they will produce the whole, my Lord, then I

can see whether one part contradicts another.

L. Ch. Just. Well, if you have any Witnesses call them.

Col. Sidney, The Earl of Anglesey.

L. Ch. Just. Ay, in God’s Name, stay till to morrow in things

that are pertinent.

Col. Sidney. I desire to know of my Lord Anglesey, what my

Lord Howard said to him concerning the Plot that was broken out.

L. Anglesey. Concerning this Plot you are now questioned for?

Col. Sidney. The Plot for which my Lord Russel and I was in

Prison.

L. Anglesey. The Question I am asked, is, what my Lord Ho-

ward said before the Tryal of my Lord Russel, concerning the

Plot; I suppose, this goes as a branch of that he was accused for.

I was then in the Country, when the Business was on foot, and

[36]

used to come to Town a day or two in the Week, living near in

Hertfordshire, and I understanding the Affliction my Lord of Bed-

ford was in, I went to give my Lord a Visit, we having been ac-

quaintance of above fifty years standing, and bred together in

Maudlin Colledge in Oxford. When I came to my Lord of Bedford,

and had administred that comfort that was fit for one Christian to

give another in that distress, I was ready to leave him, and my

Lord Howard came in. It was upon the Friday before my Lord

Howard was taken, he was taken (as I take it) upon Sunday or

Munday, my Lord Howard fell into the same Christian Office that

I had been just discharging, to compassionate my Lords afflicti-

on, to use Arguments to comfort and support him under it, and

told him, he was not to be troubled, for he had a discreet, a

wise and a vertuous Son, and he could not be in any such Plot.

(I think that was the word he used at first, though he gave another

name to it afterward) and his Lordship might therefore well expect

a good Issue of that business, and he might believe his Son secure,

for he believed he was neither guilty, nor so much as to be sus-

pected. My Lord proceeded further, and did say, that he knew of

no such barbarous Design (I think we called it so in the second

place) and could not charge my Lord Russel with it, nor any bo-

dy else. This was the effect of what my Lord Howard said at that

time, and I have nothing to say of my own knowledge more

than this; but to observe that I was present when the Jury did

put my Lord Howard particularly to it; what have you to say to

what my Lord Anglesey testifies against you? My Lord, I think

did in three several places, give a short account of himself, and

said it was very true, and gave them some further account why he

said it, and said, he should be very glad it might have been advan-

tagious to my Lord Russel.

Col. Sidney. My Lord of Clare, I desire to know of my Lord of

Clare, what my Lord Howard said concerning this Plot and me.

Lord Clare. My Lord, a little after Colonel Sidney was taken,

speaking of the Times, he said, that if ever he was questioned a-

gain, he would never plead, the quickest dispatch was the best,

he was sure they would have his Life, though he was never so

innocent, and discoursing of the late Primate of Armaghs Prophe-

sie; for my part, says he, I think the Persecution is begun, and I

believe it will be very sharp, but I hope it will be short, and I

said, I hoped so too.

Mr. At. Gen. What answer did your Lordship give to it?

Lord Clare. I have told you what I know, my Lord is too full

of discourse for me to answer all he says; but for Colonel Sidney,

he did with great asseverations assert, that he was as innocent

as any man breathing, and used great Encomiums in his praise,

and then he seemed to bemone his misfortune, which I thought

real, for never was any man more ingaged to another, than he

was to Colonel Sidney, I believe. Then I told, they talked of

[37]

Papers that were found, I am sure, says he, they can make no-

thing of any Papers of his.

Mr. Att. Gen. When was this?

Lord Clare. This was at my house the beginning of July.

Mr. At. Gen. How long before my Lord Howard was taken?

L. Clare. About a week before.

Mr. At. Gen. I would ask you, my Lord, upon your honour,

would not any man have said as much, that had been in the Plot?

L. Clare. I can’t tell. I know of no Plot.

Col. Sidney. Mr. Philip Howard.

Mr. J. Wythins. What do you ask him.

Col. Sidney. What you heard my Lord Howard say concerning

this pretended Plot, or my being in it?

Mr. Phil. Howard. My Lord, when the Plot first brake out, I

used to meet my Lord Howard very often at my Brothers house,

and coming one day from Whitehall, he asked me, what News?

I told him, my Lord, says I, there are abundance of people that

have confessed the horrid Design of murthering the King, and the

Duke. How, says he, is such a thing possible? says I, ’tis so,

they have all confessed it. Says he, do you know any of their

names? yes, says I, I have heard their Names. What are their

Names? says he, why, says I, Colonel Romsey, and Mr. West,

and one Walcott and others, that are in the Proclamation (I can’t

tell whether Walcott was in hold) says he, ’tis impossible such a

thing can be; says he, there are in all Countreys, people that

wish ill to the Government, and says he, I believe there are some

here; but says he, for any man of Honour, Interest or Estate, to

go about it, is wholly impossible. Says I, my Lord, so it is, and

I believe it. Says I, my Lord, do you know any of these peo-

ple? No, says he, none of them; only one day, says he, passing

through the Exchange, a man saluted me, with a Blemish upon

his Eye, and he embraced me, and wished me all happiness;

says he, I could not call to mind who this man was: but after-

wards, I recollected my self, that I met him at my Lord Shaftsbu-

ries, and heard afterwards, and concluded his name to be —-

his at whose house the King was to be assassinated —–

Mr. At. Gen. Rombald.

Mr. Howard. Ay, Rombald. My Lord, May I ask, if my Lord

Howard be here?

L. C. J. He is there behind you.

Mr. Howard. Then he will hear me. My Lord says I, what does

your Lordship think of this business? says he, I am in a maze; says

I, if you will be ruled by me, you have a good opportunity to

Address to the King, and all the discontented Lords, as they

are called; and to shew your Detestation and Abhorrence of this

thing; for, says I, this will be a good means to reconcile all things.

Says he, you have put one of the best Notions in my Head that ever

was put. Says I, You are a very good Pen-man, draw up the first

[38]

Address (and I believe, I was the first that mentioned an Address,

you have had many an one since, God send them good success)

says he. I am sorry my Lord of Essex is out of Town, he should

present it. But says I, Here is my Lord Russel, my Lord of Bedford,

my Lord of Clare, all of you that are disaffected, and so accom-

pted, go about this business, and make the Nation happy, and King

happy. Says he, will you stay till I come back? Ay, says I, if you

will come in any time; but he never came back while I was there.

The next day, I think, my Lord Russel was taken, and I came and

found him at my Brother’s House again (for there he was day and

night) says he, Cozen, what News? Says I, my Lord Russel is sent

to the Tower. We are all undone then, says he. Pray, says he, go

to my Lord Privy-Seal, and see if you can find I am to be taken up,

says he, I doubt ’tis a Sham-Plot, if it was a true Plot, I should fear

nothing; says I, what do you put me to go to my Lord Privy-Seal

for? He is one of the King’s Cabinet Counsel, do you think he

will tell me? I won’t go; but says I, if you are not Guilty, why

would you have me go to inquire? why, says he, because I fear

’tis not a true Plot, but a Plot made upon us, and therefore, says

he, there is no man free. My Lord, I can say no more as to that

time, (and there is no man that fits here, that wishes the King bet-

ter than I do.) The next thing I come to, is this, I came the third

day, and he was mighty sad and melancholy, that was when Col.

Sidney was taken: says I, why are you melancholy, because Col.

Sidney is taken? Says I, Col. Sidney was a man talked of before, why,

you were not troubled for my Lord Russel, that is of your Blood,

says he, I have that particular Obligation from Col. Sidney, that no

one man had from another. I have one thing to say farther, I pray

I may be rightly understood in what I have said.

L. C. J. What, you would have us undertake for all the people

that hear you? I think you have spoken very materially, and I will

observe it by and by to the Jury.

Col. Sidney. Pray call Doctor Burnet.

Mr. Just. Walcott. What do you ask Doctor Burnet?

Col. Sidney. I have only to ask Dr. Burnet, whether after the

News of this pretended Plot, my Lord Howard came to him? And

what he said to him?

Dr. Burnet. My Lord, the day after this Plot brake out my Lord

Howard came to see me, and upon some discourse of the Plot, with

Hands and Eyes lifted up to Heaven, he protested he knew no-

thing of any Plot, and believed nothing of it, and said, that he

looked upon it as a ridiculous thing.

My Lord Pagett was sent for at the Prisoners request, be-

ing in the Hall.

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I desire Joseph Ducas may be called, (who

appeared, being a French-man.)

Col. Sidney. I desire to know, whether he was not in my House

when my Lord Howard came thither, a little after I was made a

Prisoner, and what he said upon it?

[39]

Ducas. Yes, my Lord, my Lord Howard came the day after the

Colonel Sidney was taken, and he asked me, Where was the Col.

Sidney? and I said, he was taken by an Order of the King; and

he said, oh Lord! what is that for? I said, they have taken Pa-

pers; he said, Is some Papers left? yes, Have they taken some-

thing more? No, well you must take all the things out of the

house, and carry them to some you can trust: I dare trust no body,

says he; I will lend my Coach and Coach-man I said, if the Col.

Sidney will save his Goods; he save them, if not, ’tis no matter.

A little after the Lord Howard came in the House of Col. Sidney

about eleven a Clock at Night. When he was in, I told him, what

is this? They talk of a Plot to Kill the King and the Duke, and I

told him, they spake of one general Insurrection: and I told him

more, that I understood that Col. Sidney was sent into Scotland:

when my Lord Howard understood that, he said, God knows, I

know nothing of this, and I am sure if the Col. Sidney, was con-

cerned in the matter, he would tell me something, but I know no-

thing. Well my Lord, I told him, I believe you are not safe in

this house, there is more danger here than in another place.

Says he, I have been a Prisoner, and I had rather do any thing in

the World than be a Prisoner again.

Then my Lord Pagett came into the Court.

Col. Sidney. Pray my Lord be pleased to tell the Court, if my

Lord Howard has said any thing to you concerning this late pre-

tended Plot, or my being any party in it.

Lord Pagett. My Lord, I was Subpœna`d to come hither, and

did not know upon what accompt. I am obliged to say, my Lord

Howard was with me presently after the breaking out of this Plot,

and before his appearing in that part which he now Acts, he came

to me; and I told him, That I was glad to see him abroad, and

that he was not concerned in this disorder. He said, he had Joy

from several concerning it, and he took it as an injury to him, for

that it looked as if he were Guilty. He said, he knew nothing of

himself, nor any body else. And though he was free in discourse, and

free to go into any Company indifferently; yet he said, he had not

seen any body that could say any thing of him, or give him oc-

casion to say any thing of any body else.

Col. Sidney. Mr. Edward Howard.

Mr. Ed. Howard. Mr. Sidney, what have you to say to me?

Col. Sidney. My Lord, I desire you would ask Mr. Edward Ho-

ward the same thing, what Discourse he had with my Lord Ho-

ward about this Plot?

L. C. J. Mr. Howard, Mr. Sidney desires you to tell what Dis-

course you had with my Lord Howard about this Plot.

Mr. E. Howard. My Lord, I have been for some time ve-

ry intimate with my Lord, not only upon the account of our

Alliance, but upon a strict intimacy and correspondence

[40]

of friendship, and I think, I was as much his as he

could expect from that Alliance. I did move him during this

time, to serve the King upon the most honourable account I could,

but that proved ineffectual: I pass that, and come to the business

here. Assoon as the Plot brake out, my Lord having a great in-

timacy with me, expressed a great detestation and surprizing in

himself to hear of it, wherein my Lord Howard assured me under

very great Asseverations, that he could neither accuse himself,

nor no man living. He told me moreover, That there were cer-

tain persons of quality whom he was very much concerned for,

that they should be so much reflected upon or troubled, and he

condoled very much their condition both before and after they

were taken. My Lord, I believe in my Conscience, he did this

without any Mental Reservation, or Equivocation, for he had no rea-

son to do it with me. I add moreover, if I have any sense of my

Lords Disposition, I think if he had known any such thing, he

would not have stood his being taken, or made his Application

to the King in this manner, I am afraid not so suitable to his qua-

lity.

L. Ch. Just. No reflections upon any body.

Mr. Howard. My Lord, I reflect upon no body, I understand

where I am, and have a respect for the place; but since your Lord-

ship has given me this occasion, I must needs say, That that

Reproof that was accidentally given me at the Tryal of my Lord

Russel, by reason of a weak Memory, made me omit some particu-

lars I will speak now, which are these, and I think they are ma-

terial: My Lord upon the discourse of this Plot did further assure

me, that it was certainly a Sham, even to his knowledge; how, my

Lord, says I, do you mean a Sham? Why, says he, such an one,

Cozen, as is too black for any Minister of publick Employment to

have devised, but, says he, it was forged by People in the dark,

such as Jesuites and Papists, and, sayes he, this is my Conscience;

says I, my Lord, if you are sure of this thing, then pray, my

Lord, do that honourable thing that becomes your quality, that

is, give the King satisfaction as becomes you; pray make an Ad-

dress under your hand to the King, whereby you express your

Detestation and Abhorrence of this thing: says he, I thank you

for your Counsel, to what Minister, says he, shall I apply my self?

I pitched upon my Lord Hallifax, and I told him of my Lords de-

sire, and I remember my Lord Howard named the Duke of Mon-

mouth, my Lord of Bedford, the Earl of Clare, and he said he was

sure they would do it; that he was sure of their Innocence, and would

be glad of the occasion: and I went to my L. Hallifax, and told him

that my Lord was willing to set it under his hand, his detestation

of this Plot, and that there was no such thing to his knowledge.

My Lord Hallifax very worthily received me, says he, I will

[41]

introduce it; but my Lord Russel being taken, this was laid

aside, and my Lord gave this reason. For, says he, there

will be so many People taken, they will be hindred. I must

needs add from my Conscience, and from my Heart, before

God and Man, that if my Lord had spoken before the King,

sitting upon his Throne, abateing for the solemnity of the

presence I could not have more believed him, from that

assurance he had in me. And I am sure from what I have said,

if I had the Honour to be of this Gentleman’s Jury I would not

believe him.

L. C. Just. That must not be suffered.

Mr. Att. Gen. You ought to be bound to your good behavi-

our for that.

L. C. Just. The Jury are bound by their Oaths to go accord-

ing to their Evidence, they are not to go by men’s conjecture.

Mr. Howard, May I go my Lord?

Mr. Att. Gen. My Lord Howard desires he may stay, we shall

make use of him.

Col. Sidney, My Lord, I spake of a Mortgage that I had of my

Lord Howard, I don’t know whether it is needful to be proved;

but it is so.

L. Howard, I confess it.

Col. Sidney, Then my Lord here is the other point, He is under

the fear, that he dare not but say what he thinks will conduce to-

wards the gaining his Pardon; and that he hath expressed, that he

could not have his Pardon, but he must first do this drudgery of

swearing. I need not say, that his Son should say, That he was

sorry his Father could not get his Pardon unless he did swear against

some others.

Col. Sidney. Call Mr. Blake (who appeared) My Lord, I desire

he may be asked, whether my Lord Howard did not tell him that

he could not get his Pardon yet, and he could ascribe it to nothing,

but that the drudgery of swearing must be over first.

Then my Lord Chief Justice asked the Question.

Mr. Blake, My Lord, I am very sorry I should be called to give a

publick account of a private Conversation, how it comes about I

don’t know. My Lord sent for me about six Weeks ago, to come

and see him. I went and we talked of News, I told him I heard

no body had their Pardon; but he that first discovered the Plot,

he told me no; but he had his Warrant for it. And, says he, I

have their Word and Honour for it; but says he I will do nothing

in it till I have further order, and says he, I hear nothing of it, and

I can ascribe it to no other reason; but I must not have my pardon

till the drudgery of swearing is over. These words my Lord said,

I believe my Lord won’t deny it.

[42]

Then Mr. Sidney called Mr. Hunt and Burroughs,

but they did not appear.

Col Sidney, ‘Tis a hard case they don’t appear, One of them was

to prove that my Lord Howard said he could not have his Pardon

till he had done some other Jobs.

L. C. Just. I can’t help it, If you had come for assistance from

the Court I would willingly have done what I could.

Then Col. Sidney mentioned the Duke of Buckingham, but

he was informed he was not subpœna’d.

Col. Sidney, Call Grace Tracy and Elizabeth Penwick (who ap-

peared) I ask you only, what my Lord Howard said to you at my

House concerning the Plot, and my being in it?

Tracy, Sir he said, that he knew nothing of a Plot he protest-

ed, and he was sure Col. Sidney knew nothing of it. And he said

If you knew any thing of it, he must needs know of it, for he,

knew as much of your concerns as any one in the World.

Col. Sidney, Did he take God to Witness upon it?

Tracy, yes.

Col. Sidney, Did he desire my Plate at my House?

Tracy, I can’t tell that, he said the Goods might be sent to his

House.

Col. Sidney. Penwick, What did my Lord Howard say in your

hearing concerning the pretended Plot, or my Plate carrying

away?

Penwick, When he came he asked for your Honour; and they

said your Honour was taken away by a man to the Tower for the

Plot, and then he took God to Witness he knew nothing of it, and

believed your Honour did not neither. He said he was in the Tower

two years ago, and your Honour, he believed, saved his Life.

Col. Sidney, Did he desire the Plate?

Penwick. Yes, And he said it should be sent to his House to

be secured. He said it was only Malice.

Mr. Wharton stood up.

Mr. Wharton. ‘Tis only this I have to say, That if your Lord-

ship pleases, to shew me any of these sheets of Paper I will under-

take to imitate them in a little time that you shan’t know which

is which. ‘Tis the easiest hand that ever I saw in my life.

Mr. Att. Gen. You did not write these Mr. Wharton?

Mr. Wharton. No; but I will do this in a very little time if you

please.

[43]

L. C. Just. Have you any more Witnesses?

Col. Sidney. No, my Lord.

L. C. Just. Then apply your self to the Jury.

Col. Sidney. Then this is that I have to say. Here is a huge

Complication of Crimes laid to my Charge: I did not know at first

under what Statute they were, now I find ’tis the Statute of 25 of

Ed. 3. This Statute has two Branches; one relating to War, the

other to the Person of the King. That relating to the Person of

the King, makes the Conspiring, Imagining, and Compassing his

Death, criminal. That concerning War is not unless it be Levyed:

Now my Lord I cannot imagine to which of these they refer my

Crime, and I did desire your Lordship to explain it. For to say that

a Man did meet to Conspire the King’s Death, and he that gives

you the account of the business does not speak one word of it, seems

extravagant; for Conspiracies have ever their Denomination from

that point to which they tend; as a Conspiracy to make false Coin in-

fers Instruments and the like. A Conspiracy to take away a Woman, to

kill, or rob, are all directed to that end. So Conspiring to kill the King,

must immediately aim at killing the King. The King hath two Ca-

pacities Natural and Politick, that which is the Politick can’t be

within the Statute, in that sense he never dies, and ’tis absur’d to say

it should be a fault to kill the King that can’t die: So then it must be

the natural sense it must be understood in, which must be done by

Sword, by Pistol, or any other way. Now if there be not one

word of this, then that is utterly at an end, though the Witness

had been good. The next point is concering the Levying of War.

Levying of War is made Treason there, so it be provided by Overt

Act, but an Overt Act of that never was, or can be pretended here.

If the War be not Levyed ’tis not within the Act, for Conspiring to

Levy War is not in the Act. My Lord, There is no Man that thinks

that I would kill the King that knows me, I am not a Man to have

such a design, perhaps I may say I have saved his Life once. So that

it must be by Implication, that is, It is first imagined, that I intend-

ed to raise a War, and then ’tis imagined that War should tend to the

Destruction of the King. Now I know that may follow, but that

is not Natural or necessary, and being not Natural or necessary,

it can’t be so understood by the Law. That it is not it plain; for ma-

ny Wars have been made, and the Death of the King has not fol-

lowed. David made War upon Saul, yet no body will say he sought

his Death, he had him under his power and did not kill him, David

made War upon Ishbosheth, yet did not design his Death; and so in

England and France Kings have been taken Prisoners, but they

did not kill them. King Stephen was taken Prisoner, but they did

not kill him. So that ’tis two distinct things, to make War and to

endeavour to kill the King. Now as there is no manner of pre-

tence that I should endeavour to kill the King directly, so it can’t

be by inference, because ’tis Treason under another Species. I con-

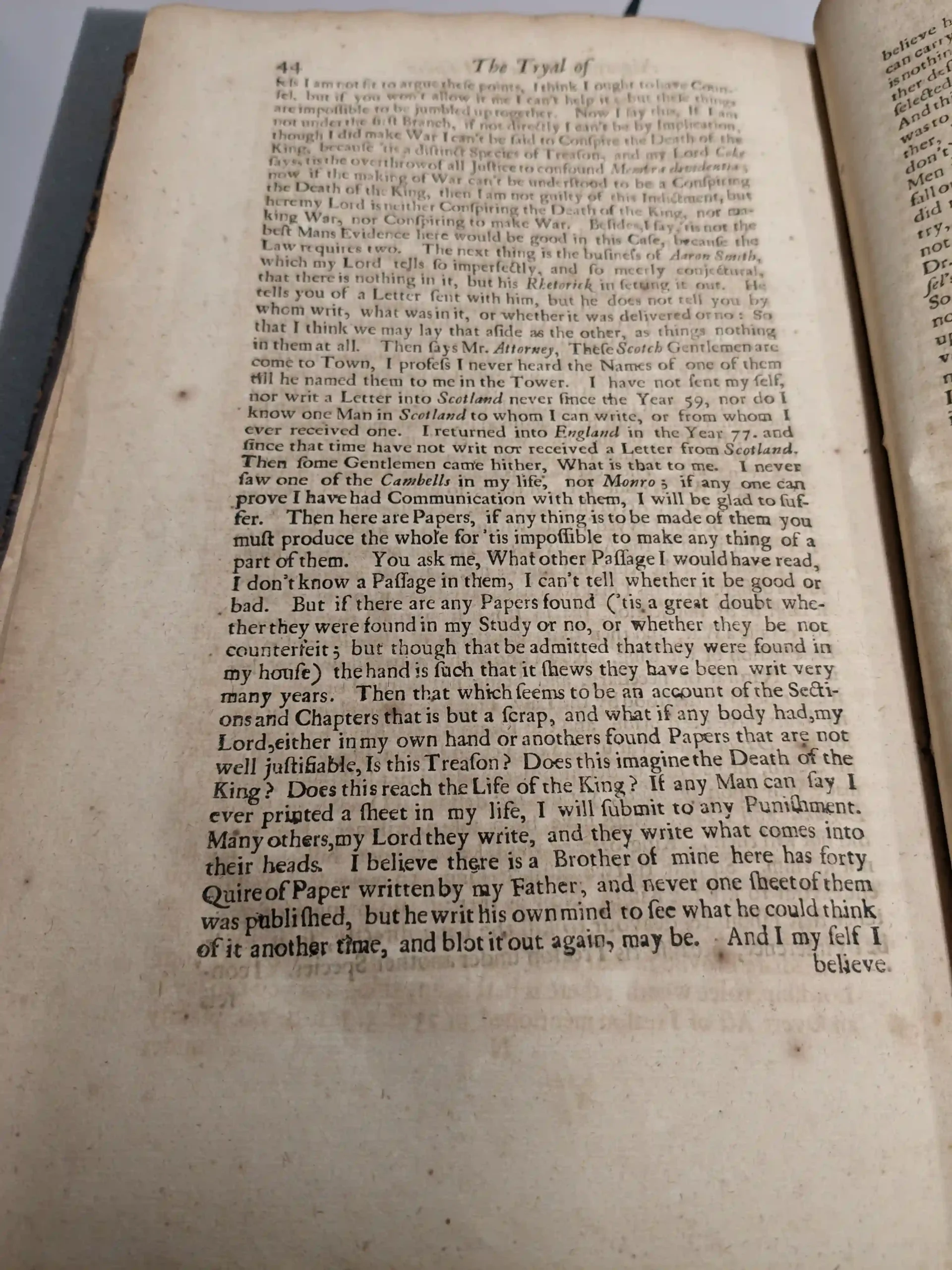

[44]

fess I am not fit to argue these points, I think I ought to have Coun-

sel, but if you won’t allow it me I can’t help it; but these things

are impossible to be jumbled up together. Now I say this, If I am

not under the first Branch, if not directly I can’t be by Implication,

though I did make War I can’t be said to Conspire the Death of the

King, because ’tis a distinct Species of Treason, and my Lord Coke

says, tis the overthrow of all Justice to confound Membra dividentia;

now if the making of War can’t be understood to be a Conspiring

the Death of the King, then I am not guilty of this Indictment, but

here my Lord is neither Conspiring the Death of the King, nor ma-

king War, nor Conspiring to make War. Besides, I say, ’tis not the

best Mans Evidence here would be good in this Case, because the

Law requires two. The next thing is the business of Aaron Smith,

which my Lord tells so imperfectly, and so meetly conjectural,

that there is nothing in it, but his Rhetorick in setting it out. He

tells you of a Letter sent with him, but he does not tell you by

whom writ, what was in it, or whether it was delivered or no: So

that I think we may lay that aside as the other, as things nothing

in them at all. Then says Mr. Attorney, These Scotch Gentlemen are

come to Town, I profess I never heard the Names of one of them

till he named them to me in the Tower. I have not sent my self,

nor writ a Letter into Scotland never since the Year 59, nor do I

know one Man in Scotland to whom I can write, or from whom I

ever received one. I returned into England in the Year 77. and

since that time have not writ nor received a Letter from Scotland.

Then some Gentlemen came hither, What is that to me. I never

saw one of the Cambells in my life, nor Monro; if any one can

prove I have had Communication with them, I will be glad to suf-

fer. Then here are Papers, if any thing is to be made of them you

must produce the whole for ’tis impossible to make any thing of a

part of them. You ask me, What other Passage I would have read,

I don’t know a Passage in them, I can’t tell whether it be good or

bad. But if there are any Papers found ( ’tis a great doubt whe-

ther they were found in my Study or no, or whether they be not

counterfeit; but though that be admitted that they were found in

my house) the hand is such that it shews they have been writ very

many years. Then that which seems to be an account of the Secti-

ons and Chapters that is but a scrap, and what if any body had, my

Lord, either in my own hand or anothers found Papers that are not

well justifiable, Is this Treason? Does this imagine the Death of the

King? Does this reach the Life of the King? If any Man can say I

ever printed a sheet in my life, I will submit to any Punishment.

Many others, my Lord they write, and they write what comes into

their heads. I believe there is a Brother of mine here has forty

Quire of Paper written by my Father, and never one sheet of them

was published, but he writ his own mind to see what he could think

of it another time, and blot it out again, may be. And I my self I