Richard Nisbet

Richard Nisbet – Slavery Not Forbidden by Scripture

(1773)

Introduction

Richard Nisbet was a West Indian enslaver who was residing in Philadelphia. In 1773, Nisbet published a pamphlet as a response to Benjamin Rush’s antislavery work, An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, Upon Slave-Keeping. Rush, arguably America’s most famous physician in the latter part of the 18th Century, wrote the pamphlet in order to lend support to other abolitionists efforts to petition the colonial assembly of Pennsylvania. Nisbet’s pamphlet was a defense of not only the institution of slavery, but West-Indian slaveholders like himself.

Nisbet’s pamphlet represents a somewhat rare early defense of slavery. While slavery certainly had its defenders within the British Empire, Nisbet’s pamphlet is somewhat unique in that it pioneers many of the arguments that would come to define the “positive good” thesis of the 19th Century. In his defense of the institution, Nisbet essentially says that Africans are not only suited for slavery, but that enslavement helps them. Not many works before this had taken such a bold stance in defending slavery.

What might have been different by 1773 to encourage Nisbet to defend slavery in such a way? What arguments does Nisbet use to justify the institution of slavery? Why might Nisbet have felt compelled to defend West-Indian enslavers like himself? Does Nisbet acknowledge the ongoing imperial conflicts between the mainland British colonies and the metropole?

Sources

- Richard Nisbet. Slavery Not Forbidden by Scripture. Or a Defence of the West-India Planters, From the Aspersion Thrown Out Against Them, By the Author of a Pamphlet, Entitled “An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, Upon Slave-Keeping.” (Philadelphia: Printed for John Sparhawk, 1773).

- Document images courtesy of Cornell University Special Collections, Rare Books E441 .M46 v.269 no.22

- Transcriptions by Michael Becker, Dylan Bails, and Joseph Douek.

Cite this page

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

SLAVERY

NOT FORBIDDEN BY

SCRIPTURE.

OR A DEFENCE

OF THE

WEST-INDIA PLANTERS,

FROM THE ASPERSIONS THROWN OUT AGAINST

THEM, BY THE AUTHOR OF A PAMPHLET, ENTITLED,

“AN ADDRESS TO THE INHABITANTS OF

“THE BRITISH SETTLEMENTS IN AMERICA, UPON

“SLAVE-KEEPING.”

BY A WEST-INDIAN.

Who steals my Purse, steals trash, ’tis something, nothing;

‘Twas mine, ’tis his, and has been slave to thousands ;

But he that filches from me my good Name,

Robs me of that, which not enriches him,

And makes me poor indeed. SHAKESPEARE.

PHILADELPHIA.

PRINTED by John SparhawkM,DCC,LXXIII.

PREFACE.

CONSCIOUS of a want of abilities, and

having very little time to spare at present, it

distresses me, not a little, to write any thing that

has a chance of being perused by the publick.

I never should have attempted to contradict the

author of the address, merely from being a native

of the West-Indies, for I hate national partiality ;

but as I have many valuable friends in that part

of the world, I could not, patiently, hear them so

unworthily traduced, without endeavouring to un-

deceive his readers.

I very well know, that slave keeping is thought

inconsistent with religion, by great part of the peo-

ple in this province, so that what I have said, con-

cerning its legality, or the political necessity of ad-

mitting it, may be read with disgust by many.

[ii]

I have not vanity enough to think, that any

thing I have mentioned, will incline them to change

their opinions, or to look upon it with a more fa-

vourable eye. But I flatter myself, that every ho-

nest man, whatever his religious or political princi-

ples may be, will favour every attempt to crush the

most malevolent slander, especially when it is exag-

gerated beyond the most distant bounds of probability.

The inhabitants of this city will please to recollect,

that the West-Indies form a considerable branch of

their commerce, and that they ought therefore to

listen to every thing that can be said in favour of its

inhabitants. They will, likewise, remember that

they lately received a genteel sum of money from that

quarter, for the use of their college, for which act

of generosity I heard the West Indians highly com-

mended, by the Provost of that seminary, on a late

publick occasion. Every one must suppose that he,

likewise, spoke the sentiments of the other professors,

and surely those gentlemen, equally remarkable for

their piety and learning, would not have bestowed

praises where they were not due, nor deigned to re-

ceive any donations, if they thought they were

granted by monsters and barbarians.

[iii]

I trust to facts, and the goodness of my cause,

rather than elegant language and flowery decla-

mation ; and I must observe, that, though I am in-

finitely inferior to the author of the address, in the

qualifications of a writer, yet I have many advan-

tages over him.

Abuse levelled at an entire body of people, seems

so contrary to reason, and every charitable maxim,

that a man who undertakes it, though of the first

rate genius, lays himself open to be refuted by eve-

ry school boy. Such performances, unless supported

by the poetick fire of a Churchill, cannot bear a se-

cond reading, and must soon sink into utter oblivion.

SLAVERY

NOT FORBIDDEN BY

SCRIPTURE.

OR A DEFENCE, &c.

MANY writers, who aim at the reformation of

mankind, point out plans for their conduct,

which it is impossible to follow. They make no allow-

ance for our frailties, nor consider that we cannot at-

tain a state of absolute perfection. Among the rest, the

declaimers against slavery never recollect that there are

faults in every human institution. Instead of advising

some wholesome regulations and improvements, they

spend their time in fruitless reproaches, and afterwards

declare that slavery ought to be utterly abolished, as if

their dictates were to be implicitly followed. Till self-

interest ceases to have influence over the actions of men,

( 2 )

proposals that strike at the very root of their temporal

concerns will never be pursued, and serve no other pur-

pose, than to display the author’s talents.

A MAN of a gloomy and discontented turn of mind,

who has no other view in offering his sentiments to the

publick, than to make an ostentatious shew of his abili-

ties, may write numberless folios on the abuses that

reign among us, and still find fresh subject for complaint.

Why does he not pour forth his eloquence against the

lawless ambition of kings, who, for a spot of land, per-

haps, not fit to defray half the expences of a campaign,

often sacrifice millions of their fellow creatures? The

occupations of their subjects, when viewed through the

magnifying medium of a bigot’s eye, are likewise equal-

ly deserving of censure. The servants of the state, un-

der colour of perquisites of office, confiscate the public

money ; Bishops preach on humility and indifference to

worldly enjoyments, yet pocket ten thousand a year;

lawyers are ready to engage on either side of a cause,

perhaps, by their eloquence mislead the jury, and occa-

sion the ruin of widows and orphans ; physicians take a

fee from a patient, when they know his cure to be im-

possible; and the efforts of a merchant to get the best

price for his commodities, must appear an endless en-

deavour of one man to over-reach another. Most of

our favourite sports exhibit a continued scene of blood-

shed and cruelty. What enjoyment can a rational mind

feel in pursuing a timid hare, and seeing the poor animal

worried by dogs; or in maiming a harmless partridge ?

Can there be any satisfaction in torturing the worm and

( 3 )

trout, for hours, on the sharp-pointed hook ? Is it not

the height of barbarity to push the generous horse be-

yond his strength, and make him run over a course of

some miles in a few minutes ? In short, it would be end-

less to mention every circumstance that an enthusiast

may lay hold of, to prove the degeneracy of human na-

ture. He may always find subjects enough to exercise

his declamatory powers, without having recourse to sla-

very. The man of a liberal and benevolent way of

thinking, will see that there are faults in all employ-

ments, and that many of our amusements cannot be

justified by the strict rules of humanity; but he will

overlook such matters, seeing they are the necessary

consequences of the imperfection of our nature. In

his own department he will keep himself as free

from blame as possible; and be of opinion, that the small

portion of time every good member of society has to

spare from his own concerns, is better employed in pro-

moting the happiness of mankind, than in railing at

their vices.

SLAVERY, like all other human institutions, may

be attended with its particular abuses, but that is not

sufficient totally to condemn it, and to reckon every one

unworthy the society of men who owns a negro.

IF precedent constitutes law, surely it can be defend-

ed, for it has existed in all ages. The scriptures, in-

stead of forbidding it, declare it lawful. The divine

legislator, Moses, says —

( 4 )

” BOTH thy bond-men and thy bond maids, which

thou shalt have, shall be of the heathen that are round

about you; of them shall ye buy bond-men and bond-

maids. Moreover, of the children of the strangers that

do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy, and of

their families that are with you, which they beget in

your land: and they shall be your possession. And ye

shall take them as an inheritance for your children after

you, to inherit them for a possession, they shall be your

bond-men for ever. *Levit. xxv. 44, 45. 46.“

THE Jews are not only allowed, in the clearest

terms, to enslave the heathens for life, but like-

wise others, who were their countrymen, though of a

different religious persuasion

IN another place, † Exod. xxi. 20./mfn]giving laws concerning serv-

ants, he says–

“AND if a man smite his servant or his maid, with

a rod, and he die under his hand, he shall be surely

punished; notwithstanding, if he continue a day or two,

he shall not be punished: for he is his money.”

KILLING a servant on the spot seems was punish-

ed, though not capitally : for, in the same chapter, he

mentions six capital crimes, and always expresses in the

most direct terms that the delinquent shall suffer death.

We can not easily infer the same meaning from the

( 5 )

word punished. He probably meant a pecuniary fine,

especially, as in the verse that immediately follows, he

uses the very same words, “he shall be surely punished,”

to express a forfeiture of money. §If men strive and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart from her, and yet no mischief follow: he shall be surely punished, according as the woman`s husband will lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judge determine. ——— Exod. xxi. 22. The words his mo-

ney, plainly convey the idea of propety, as if he were

talking of an ox or an ass.

IT must be observed, that these laws, which are so

much in favour of the master, seem to have been appli-

cable only to Hebrew servants. If they were so harshly

dealt with, slaves for life, certainly, lay under still

greater disadvantages. These were distinguished by the

name of Bondmen, and I can find no laws in the Old

Testament concerning them. The heathens and strang-

ers appear to have been held in so small estimation, by

Moses and the Jews, that it is likely he did not think it

worth while to give any laws concerning them, and left

it in the will of the master, to treat them as he thought

proper. † The jews deserve censure for their illiberal partiality to their countrymen and fellow believers.

THE Author of the Address is of opinion, that

slavery was not authorized by the patriarchs, because

( 6 )

their accounts of it are very short, just as if one could

not understand an author’s meaning in a few words.

A good christian might as well pretend, that he ought

not to pay any attention to the commandment, “Thou

shalt not kill,” nor several of the others, because they

are expressed in a brief manner. With the same sophist-

ry he adds, that Providence kept the neighbouring nati-

ons in bondage, to prevent the jews from corrupting

their national religion and, by intermarriages, altering

the descent of Jesus from what was originally ordained.

COULD an eternal decree of God be overturned by

the pitiful revolutions among men? or could not the

same omnipotent being, who marked out the descent of

the saviour of the world, prevent the race of Abraham

from being corrupted? This assertion can even be con-

futed from the situation of the Jews, since their over-

throw by the Romans. They have been driven from

their native country, and scattered among all the na-

tions of the earth, many of whose manners and customs

are more inviting than their own, yet they still remain

a distinct people, in spite of persecution and all the dis-

advantages they labour under.

THE Jews are forbidden to detain their countrymen

in servitude longer than seven years. ¶Hebrew servants were not allowed to carry their wives and children with them if they belonged to their master, and, probably, from a reluctance to quit such ten- [continued pg. 7] -der connections, they sometimes refused to go away at the end of seven years, and voluntarily became slaves for life. This was ratified in due form by a very cruel ceremony, namely, boring the servant`s ear with an awl, and fastning him to a door or a post.—– ” If his master have given him a wife, and she have borne him sons or daughters; the wife and her children shall be her masters, and he shall go out by himself. “And if the servant shall plainly say, I love my master, my wife and children, I will not go out free : Then his master shall bring him unto the judges; he shall also bring him to the door, or unto the door post: “And his master shall bore his ear through with an awl; and he shall serve him forever.” Exodus xxi. 4, 5, 6. ” And it shall be if he say unto thee, I will not go away from thee ( because he loveth thee and thine house: because he is well with thee) “Then thou shall take an awl, and thrust it though his ear unto the door, and he shall be thy servant for ever : And also unto they maid-servant thou shaly do likewise, Deut. xv. 16, 17. We do the same,

( 7 )

though they should be wretches, guilty of the most fla-

grant violation of the laws. Neither are they to steal

one another; a crime which we have no cause to be ac-

cused of. Kidnapping seems to have been common

( 8 )

with the Jews, for Moses denounces his vengeance a-

gainst it in more places than one. *Exod. xxi. 16. Deut. xxiv. 7.

OUR Saviour’s general maxims of charity and bene-

volence, cannot be mentioned as proofs against slavery.

If the custom had been held in abhorrence by Christ and

his disciples, they would, no doubt, have preached a-

gainst it in direct terms. They were remarkable for the

boldness †Witness Paul`s behaviour before Agrippa. of their discourses, and intrepidity of con-

duct, which brought on them persecutions, imprison-

ment, and even death itself. However, the Addresser

is so wicked as to accuse our Saviour of the meanest dissi-

mulation, by saying, that he forbore to mention any

thing that might seem contrary to the Roman or Jew-

ish laws This Gentleman, attempting to be religious,

becomes blasphemous. Enough, I believe, has been

said, to shew his inability to prove that slavery is con-

trary to scripture.

IF this writer had confined himself to the impropriety

of slavery in this, and some of the other colonies, and

treated the subject in an unprejudiced manner, his la-

bours might have been useful. In the northern parts

of America there are now, numbers of industrious white

inhabitants, and when that is the case, the importation

of Negroes will cease, without any interposition of the

legislature. No man who pays attention to his interest

and peace of mind, will ever employ slaves to do his

work, when he can get freemen at a moderate price.

( 9 )

But his proposal of settling the West-Indies entirely with

whites, and giving the Negroes their liberty, could ne-

ver come from a man of common sense. *To prove that negroes earn their freedom, our Author rates the profits of their yearly labour, at ten pound sterling, and their expences, forty shillings, but, including taxes, food, cloathing, doctors fees and the interest of the original cost of a Negro, it is well known that his yearly charges will amount to near eight pound. Besides, how can he be certain that the Negro will labour twenty years, when the life of a healthy person can only be valued seven years. I mention this, to shew that he is totally unacquainted with his subject. The Author

of the Address has, certainly, never been in the sugar

islands, and consequently, whatever he mentions, con-

cerning them, must be from a confused hear-say, not

from experience.

I IMAGINE there are above four-hundred thousand

Negroes in the British islands: Can he point out a plan

to procure the same number of whites in their stead?

Or, if they could be got, would not there be a necessity

for vast reinforcements, to supply the place of those cut

off by disease? Where is the money to be raised to make

satisfaction to the Planters to the loss of their proper-

rty? †Fifty-two millions would be required; twenty-two millions for the Negroes, and thirty in consideration of the lands, buildings, &c. The people in Britain already complain, that

emigrators, from the mother country, are become too

( 10 )

numerous; and when they take the resolution of going

abroad, they will certainly prefer the interior parts of

America to the rugged rocks of the West-Indies, or the

swamps of Carolina, as more likely to secure them every

comfort of life. Many articles of subsistence, very

necessary to families that come from Europe, such as,

milk, butter and cheese, can hardly be procured in the

West-Indies, and no kind of grain, can be raised, ex-

cept Guinea and Indian corn, with which they are

totally unacquainted.

WITH regard to the Africans, they meet with few

inconveniences of that nature, as the climate and pro-

ductions of the two countries are so nearly alike.

THIS writer confesses, that hard labour within the

tropics shortens human life, and that the colour of the

negroes qualifies them for hot countries, yet he is desir-

ous, that our white fellow subjects should toil in these

sultry climates, that the Africans might indulge their

natural laziness in their own country. The former are,

no doubt, much obliged to him for his kind intentions.

TO support his benevolent scheme of abolishing slave-

ry in the Islands, he makes use of a very specious argu-

ment, that agriculture can never flourish where slavery is

tolerated. If he means the slavery of arbitrary states,

he may be right, but with regard to the British West-

Indies, where the proprietors are under a free govern-

ment, and only the manual labour performed by slaves,

( 10 )

numerous; and when they take the resolution of going

abroad, they will certainly prefer the interior parts of

America to the rugged rocks of the West-Indies, or the

swamps of Carolina, as more likely to secure them every

comfort of life. Many articles of subsistence, very

necessary to families that come from Europe, such as,

milk, butter and cheese, can hardly be procured in the

West-Indies, and no kind of grain, can be raised, ex-

cept Guinea and Indian corn, with which they are

totally unacquainted.

WITH regard to the Africans, they meet with few

inconveniences of that nature, as the climate and pro-

ductions of the two countries are so nearly alike.

THIS writer confesses, that hard labour within the

tropics shortens human life, and that the colour of the

negroes qualifies them for hot countries, yet he is desir-

ous, that our white fellow subjects should toil in these

sultry climates, that the Africans might indulge their

natural laziness in their own country. The former are,

no doubt, much obliged to him for his kind intentions.

TO support his benevolent scheme of abolishing slave-

ry in the Islands, he makes use of a very specious argu-

ment, that agriculture can never flourish where slavery is

tolerated. If he means the slavery of arbitrary states,

he may be right, but with regard to the British West-

Indies, where the proprietors are under a free govern-

ment, and only the manual labour performed by slaves,

( 11 )

his observation will not hold good, for there are few,

or no lands, better cultivated any where. The little

island of St. KITTS, is not above eighty miles

square, and yet, its, annual produce amounts to

half a million sterling, which is not, perhaps, to be

equalled in the whole universe.

THE history of the West-Indies, shews, that sugar

colonies can never be brought to any perfection, by di-

viding the lands among a number of people. When

the islands were first taken under the protection of go-

vernment, numbers of people settled there, who made

a shift to support themselves, by planting a little cotton

and tobacco, very little sugar or rum being then made.

Such people can afford to consume but very few manu-

factures, and those of the cheapest sort. Some of them

more ambitious and possessed of greater industry than

the rest, assisted with accidental supplies of money,

purchased the lands of many of these inconsiderable

proprietors. This increase of property enabled them

to become sugar planters, by which means they soon ac-

quired riches, and the islands, from being of little or

no use to government, greatly encreased its revenue.

It is in vain to think of making sugar, by dividing the

land into small lots among poor settlers. Unless a plan-

tation yields above fifty hogheads of that commodity, it

will hardly defray the expence of building a set of works,

buying cattle, and a variety of necessary utensils; in

short, to commence sugar planter, a man must have the

command of a very considerable sum of money ; and a

(12)

small estate being attended with a much greater propor-

tional expence than a large one, no person can expect to

become independent, unless his landed property is pret-

ty extensive.

IN this country, when the peasant reaps and thrashes

his grain, the labour is over, and he can keep it several

months, till he meets with a purchaser. But the

case is widely different with the cane planter; when

the cane is cut it is useless, unless he has the neces-

sary apparatus to manufacture it, which cannot be

procured without a great sum of money. He must quick-

ly resolve, for the cane will perish in a few hours, a cir-

cumstance that deprives him of an opportunity to trans-

port it by water carriage, or of carrying it far by land,

to find a buyer.

BY the property in the islands falling into fewer

hands, the state has lost some subjects in her colonies,

but it has received full compensation, by the additional

value of produce sent to the mother country. *I believe it will admit of dispute, whether Great-Britain has suffered a decrease of subjects on the whole, by the property in the islands falling into fewer hands. For the additional quantity of sugar, &c. thereby made and sent home, by giving employment to the refiners of sugar, sailors, ship-builders, and, in short, giving business to people in a thousand different occupations, must create an encrease of inhabitants at home; so that, upon the whole, the state can hardly be said to be a loser in that respect. I know

( 13 )

estates which formerly afforded only a scanty subsistence

to a few families, that now yield five-thousand pounds

sterling, per annum, to the proprietor, and fifteen hun-

dred to the revenue, which is infinitely more than an

estate in England of the same income. The Bristish em-

pire is one vast machine, and every particular district

and colony, may be compared to separate wheels that

give motion to the whole. Some aggrandize the state by

commerce; others by furnishing useful subjects; and it

may be said in favour of those affording wealth, that

money can command soldiers, but that soldiers without

money can never prove serviceable.

IT is now time to indulge, for a moment, the chi-

merical suppostition, that government were to listen to the

complaints of the Author of the Address, and such visi-

onary enthusiasts, and by act of parliament, declare all

the negroes free; many of the richest British subjects must

immediately become beggars, and the sugar colonies (not

to mention those that produce rice and indigo) will be

deserted. The nation must consequently pay above four

millions †The sugar annually exported from the British West-Indies, is computed to be above four millions, sterling, value.a year, to foreigners, for that commodity *If we include the value of the rum, coffee, cocoa, cotton, rice, indigo, and tobacco, made in the British colo- [continued on pg. 14] nies, there must be a loss of some millions more: Besides, we must consider the loss of freight, the number of sailors, and others, that would have no employment, and the check that the usual circulation, in the mother country, would receive, by the proprietors in the colonies, having no money to spend. It would be endless to trace the consequences; and every one must confess that Britain, without her Southern and West-India colonies, must be a mere cypher. the

( 14 )

revenue will be reduced more than another million, and

the surest vent for our manufactures would be lost. By

such terrible drains, Britain would be rendered quite

defenceless, and she must soon fall an easy prey to France,

or some of her other powerful neighbours; and thus,

by freeing the Africans, Britons, themselves, must be-

come abject slaves to despotick power.

I AM suprized these advocates for human liberty, do

not undertake the cause of our brave soldiers and invin-

cible sailors, in preference to that of the negroes; cer-

tainly every body will excuse them for so harmless a par-

tiality. They ought to advise the ministry to abolish

the inhuman custom of pressing, and to allow the sol-

diers to quit their regiments when they had a mind, in-

stead of being detained during life. If they received an

answer, they would, probably, be told, that the wisest

statesmen had never discovered any other method of

manning the navy, especially on a sudden emergency;

and that the army could not be maintained, if the time

of serving were left in the will of the soldiers. They

would, likewise, be told, that private considerations

( 15 )

must always give way to the publick good; and that the

safety of the state required these extraordinary exertions

of power. Will not the same reason oblige government

to allow slavery to continue in the colonies? By listning

to one petition, Britain must be conquered by force of

arms; by granting the other, she must be undone by

losing her commerce. The cause would be different,

but the effect the same.

I SHOULD have allowed the Author of the Address,

and his associates, to enjoy the imaginary triumph of

proving the iniquity of slavery, and quietly heard of

their petition being presented to government, to prohi-

bit the African trade, without feeling the smallest desire

to combat their opinions; but he has gone farther. He

has represented the West-India planters as a set of hardned

monsters, who, whip their slaves without any cause–ra-

vish their women—torment both sexes with melted wax

and fire— suspend them in the air by the thumbs, and

wantonly indulge themselves in every species of cruelty.

He says these pictures are taken from real life. I should

be glad to know his authority.

NO gentleman could pay so little regard to truth, as

to say, that such horrid scenes are frequently to be met

with. His information must have been received from an

obscure writer, unworthy of credit; or some gloomy, dis-

contented wretch, somewhat disordered in his understand-

ing. For my part, I never knew a single instance of

such shocking barbarities, and every West-Indian with

whom I have conversed on the subject, has made the

same declaration.

( 16 )

THE West-Indies has, now, been settled above a

hundred years, during which time, no doubt, many

men, guilty of every vice, have existed in that country,

and a few instances have happened of the cruelties he

mentions: But is that a reason to stigmatize every West-

Indian, with the name of murderer and monster, and

represent him as dead to every kind of feeling? <span>†This writer talks much of slave-keeping and breaking the eighth commandment, but he certainly ought to have perused the ninth with attention, before he favoured the world with such specimens of his skill in the assassination of characters.

MOST of the natives, of the West-Indies, are sent

to England, in the early part of their life, where they

receive a liberal education, and imbibe those senti-

ments of liberty and independence, which are every

where to be met with in that happy country. Is it

to be supposed, that a few years residence in the

West-India islands, will make them, totally, forget hu-

manity, that first and noblest characteristick of English-

men? Or will not that powerful advocate, self-interest,

persuade them to preserve their slaves in life and health,

though their hearts should become totally callous ?

This writer endeavours to prove them destitute of

common sense, as well as compassion. The West-In-

dies, I believe, is as remarkable as any of the other co-

lonies, for giving birth to men of a generous and merci-

ful disposition ; and those guilty of unusual severity are,

( 17 )

there, held in the same abhorrence, as they would be in

any other part of the world.

I HAVE no intentions to insinuate, that the planters

do not bestow proper correction when it is necessary.

If they were totally neglectful in this particular,

they would neither be lovers of justice, nor consult the

happiness of their slaves; for nobody would ever wish

the bad to enjoy the same advantages as the good.

The negroes of a very indulgent, easy master, for

the most part, become compleat villains. They not on-

ly injure their master’s property, but likewise are a nu-

sance to the neighbourhood, and for their flagrant

crimes are often punished by the laws; which might

have been prevented if they had been checked in proper

time. You have no chance to acquire the esteem of ne-

groes by never correcting them for a fault; they are

sure to laugh at your folly. It is a universal remark,

that almost every insurrection in the West-Indies, has

been hatched on the estates of over-indulgent masters,

and ten to one, his favourite servants are the ringleaders,

and strike the first blow.

THE planter who lays down a resolution, never to let

a fault pass unobserved, will soon find that there is

seldom occasion to exert his authority. The deserving

part of his negroes will maintain their good behaviour,

and the worthless, from motives of fear, take care never

to merit punishment.

( 18 )

OVERSEERS are never allowed to chastise negroes,

without acquainting the proprietor, or (if he resides in

England) the manager, who is generally a gentleman

by birth and education. His business is, only to ob-

serve that the slaves do not idle away their time, and to

inform against those that have misbehaved.

THE Addresser would make us believe, that negroes

are often put to death, by the laws, for such a trifling

transgression as stealing a bit of bread. ¶Many of the penal laws of the islands, relating to slaves, may, at first sight, appear harsh, and give an unfavourable idea of the clemency of our legislatures: but on examination, they will appear excusable and absolutely necessary to the safety and good government of the islands. The disproportion of white and black inhabitants, is there very great ; and self- preservation, that first and ruling principle of human nature, alarming our fears, has made us jealous, and perhaps severe in our threats against delinquents. Besides, if we attend to the history of our penal laws relating to slaves, I believe we shall generally find, that they took their rise from some very atrocious attempts made by the negroes, on the properties of the masters, or after some insurrection or commotion, which struck at the very being of the colonies. Under those circumstances it may very justly be supposed, that our legislatures when convened were a good deal inflamed, and might be induced for the preservation of their persons and properties, to pass many severe laws, which they might hold over their heads, to ter- [continued on pg. 19] rify and restrain them. It is strange

that he will discover his ignorance in every line. They

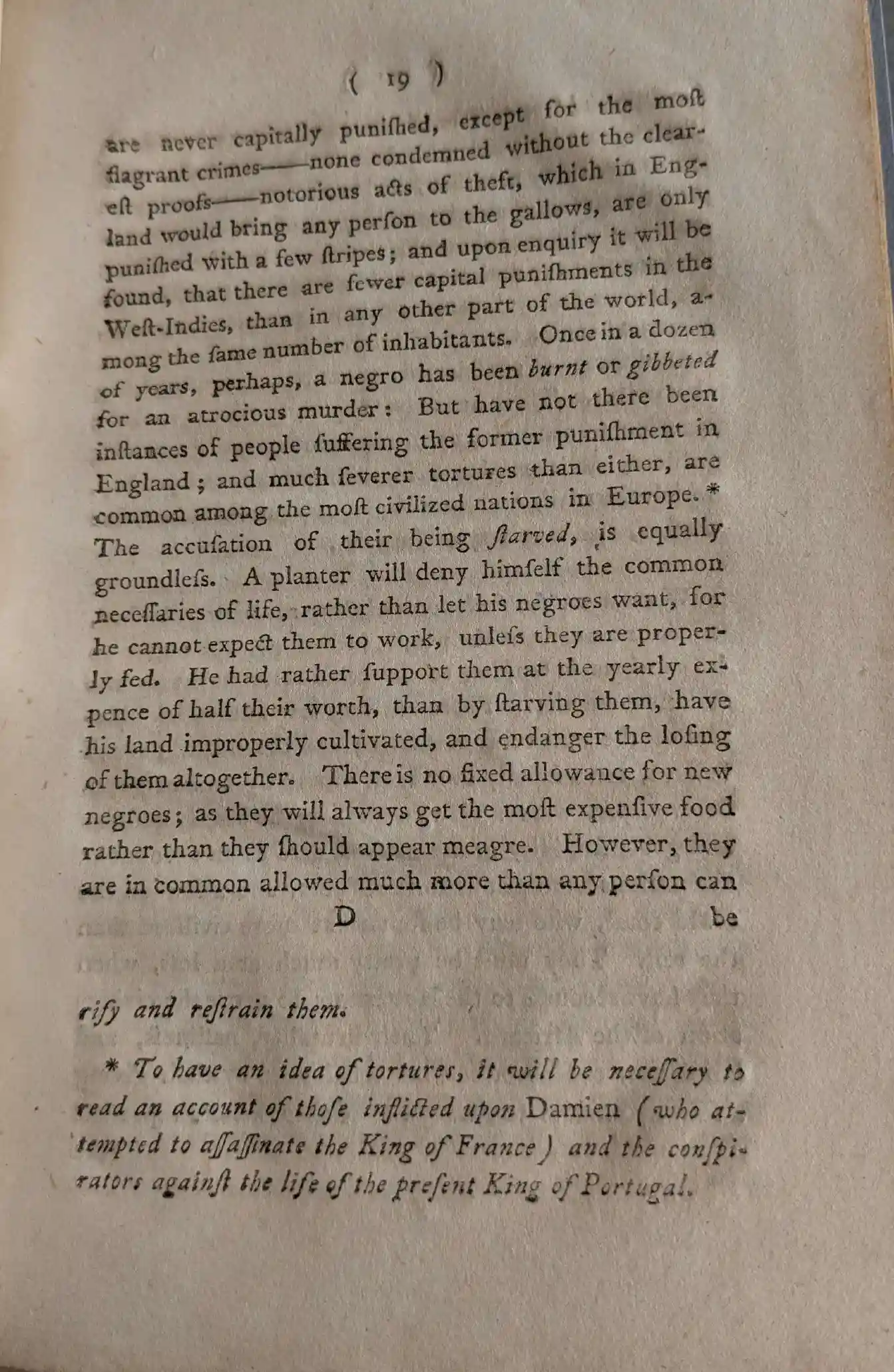

( 19 )

are never capitally punished, except for the most

flagrant crimes— none condemned without the clear-

est proofs—- notorious acts of theft, which in Eng-

land would bring any person to the gallows, are only

punished with a few stripes; and upon enquiry it will be

found, that there are fewer capital punishments in the

West-Indies, than in any other part of the world, a-

mong the same number of inhabitants. Once in a dozen

of years, perhaps, a negro has been burnt or gibbeted

for an atrocious murder : But have not there been

instances of people suffering the former punishment in

England; and much severer tortures than either, are

common among the most civilized nations in Europe. *To have an idea of tortures, it will be necessary to read an account of those inflicted upon Damien (who attempted to assassinate the King of France) and the conspirators against the life of the present King of Portugal.

The accusation of their being starved, is equally

groundless. A planter will deny himself the common

necessaries of life, rather than let his negroes want, for

he cannot expect them to work, unless they are proper-

ly fed. He had rather support them at the yearly ex-

pence of half their worth, than by starving them, have

his land improperly cultivated, and endanger the losing

of them altogether. There is no fixed allowance for new

negroes; as they will always get the most expensive food

rather than they should appear meagre. However, they

are in common allowed much more than any person can

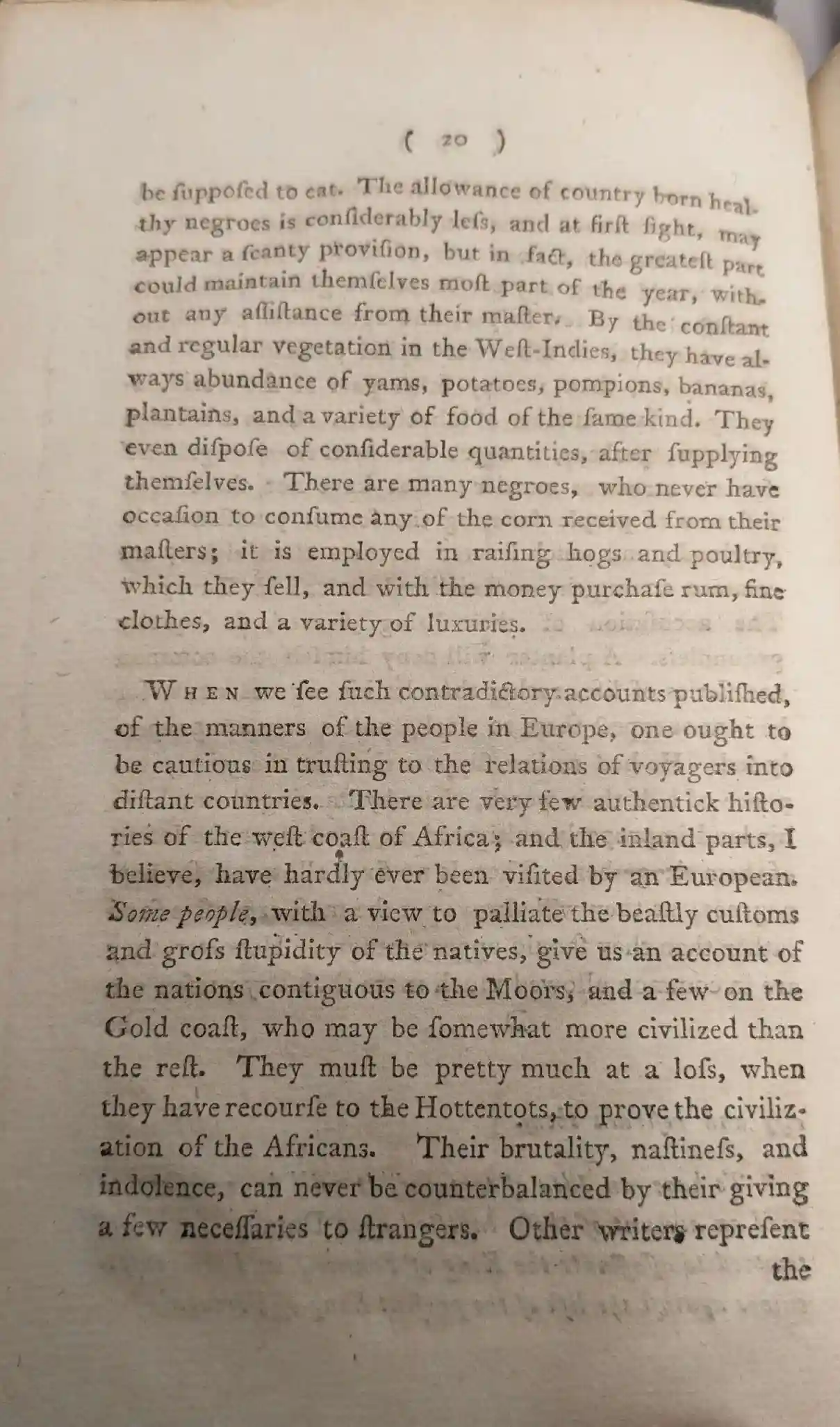

( 20 )

be supposed to eat. The allowance of country born heal-

thy negroes is considerably less, and at first sight, may

appear a scanty provision, but in fact, the greatest part

could maintain themselves most part of the year, with-

out any assistance from their master. By the constant

and regular vegetation in the West-Indies, they have al-

ways abundance of yams, potatoes, pompions, bananas,

plantains, and a variety of food of the same kind. They

even dispose of considerable quantities, after supplying

themselves. There are many negroes, who never have

occasion to consume any of the corn received from their

masters; it is employed in raising hogs and poultry,

which they sell, and with the money purchase rum, fine

clothes, and a variety of luxuries.

WHEN we see such contradictory accounts published,

of the manners of the people in Europe, one ought to

be cautious in trusting to the relations of voyagers into

distant countries. There are very few authentick histo-

ries of the west coast of Africa; and the inland parts, I

believe, have hardly ever been visited by an European.

Some people, with a view to palliate the beastly customs

and gross stupidity of the natives, give us an account of

the nations contiguous to the Moors, and a few on the

Gold coast, who may be somewhat more civilized than

the rest. They must be pretty much at a loss, when

they have recourse to the Hottentots, to prove the civiliz-

ation of the Africans. Their brutality, nastiness, and

indolence, can never be counterbalanced by their giving

a few necessaries to strangers. Other writers represent

( 21)

the Africans in different, and probably their real colours.

Though one cannot talk with any degree of certainty,

with regard to the situation of the Africans, in their own

country, yet, very just notions can be formed concern-

ing their dispositions, from the numbers which are

brought to the West-Indies from every quarter of that

extensive continent. It is impossible to determine, with

accuracy, whether their intellects or ours are superior,

as individuals, no doubt, have not the fame opportuni-

ties of improving as we have: However, on the whole,

it seems probable, that they are a much inferior race of

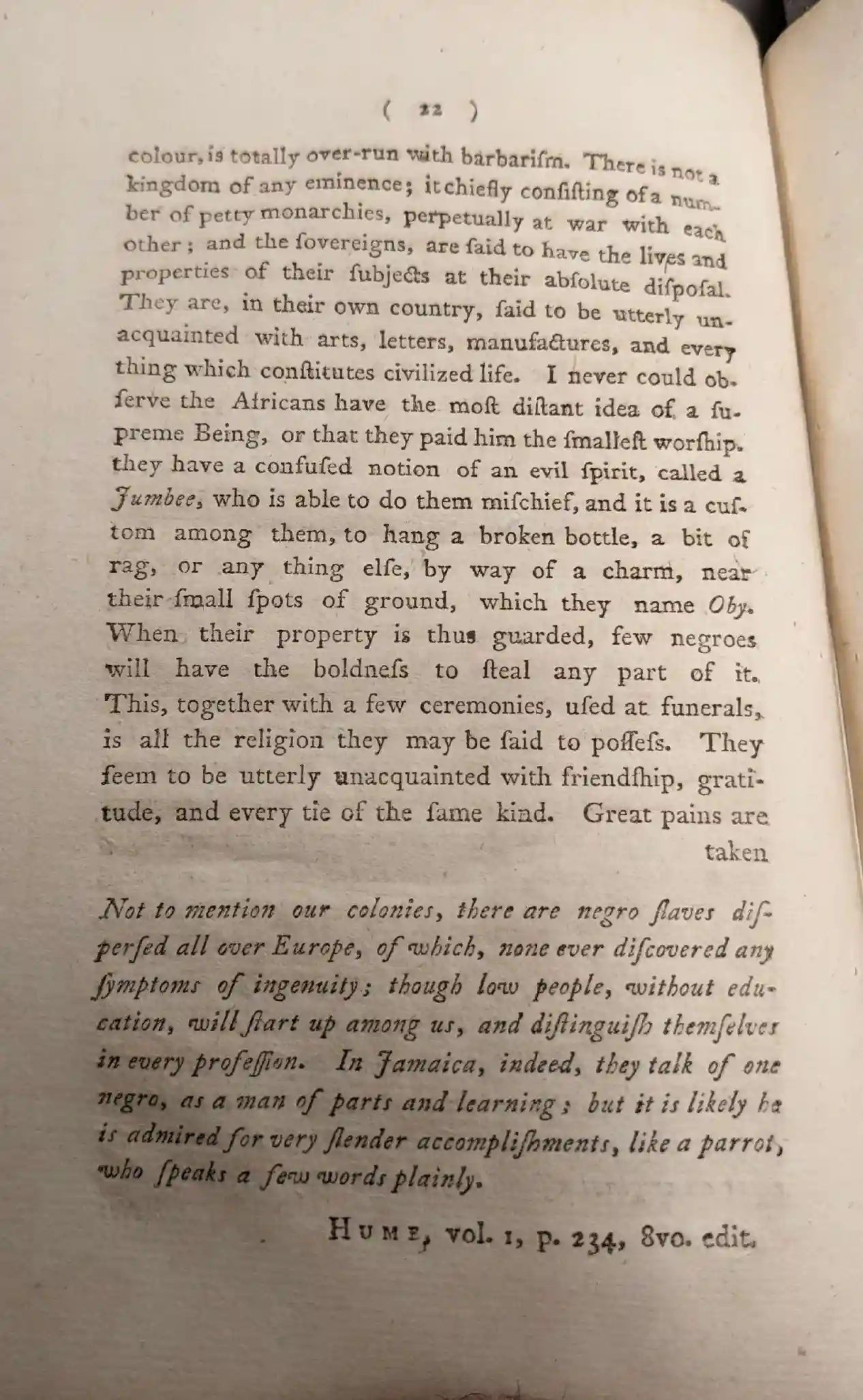

men to the whites, in every respect.* I am apt to suspect the negroes, and in general, all the other species of man (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites. There never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor ever any individual, eminent either in action or speculation. No ingenious manufactures among them, no arts, no sciences. On the other hand, the most rude and barbarous of the whites, such as the Ancient Germans, the present Tartars, have still something eminent about them, in their valour, form of government, or some other particular. Such a uniform and constant difference could not happen, in so many countries and ages, if nature had not made an original distinction, betwixt these breeds of men. [cont. on pg. 22] Not to mention our colonies, there are negro slaves dispersed all over Europe, of which, none ever discovered any symptoms of ingenuity ; though low people, without education, will start up among us, and distinguish themselves in every profession. In Jamaica, indeed, they talk of one negro, as a man of parts and learning ; but it is likely he is admired for very slender accomplishments, like a parrot, who speaks a few words plainly. HUME, vol. I, p. 234, 8vo. edit. We have no

other method of judging, but by considering their ge-

nius and government in their native country. Africa,

except the finall part of it inhabited by those of our own

( 22 )

colour, is totally over-run with barbarism. There is not a

kingdom of any eminence; it chiefly consisting of a num-

ber of petty monarchies, perpetuaally at war with each

other; and the sovereigns, are said to have the lives and

properties of their subjects at their absolute disposal.

They are, in their own country, said to be utterly un-

acquainted with arts, letters, manufactures, and every

thing which constitutes civilized life. I never could ob-

serve the Africans have the most distant idea of a su-

preme Being, or that they paid him the smallest worship.

they have a confused notion of an evil spirit, called a

Jumbee, who is able to do them mischief, and it is a cus-

tom among them, to hang a broken bottle, a bit of

rag, or any thing else, by way of a charm, near

their small spots of ground, which they name Oby.

When their property is thus guarded, few negroes

will have the boldness to steal any part of it.

This, together with a few ceremonies, used at funerals,

is all the religion they may be said to possess. They

seem to be utterly unacquainted with friendship, grati-

tude, and every tie of the same kind. Great pains are

( 23 )

taken to give a high colouring to the affecting scenes

between relations parted at the sale; </span>*A gentleman of my acquaintance assures me, that he attended most of the sales this year at Charlestown, and only saw two instances of a reluctance at parting ; and another of my friends, who was a clerk two years in one of the first Guinea houses, in Grenada, assures me, that he never saw a single instance of the kind. but I appeal

to every one who has ever been present, at the disposal

of a cargo, if he has not seen these creatures, separated

from their nearest relations without looking after them,

or wishing them farewell. A few instances may be

found, of African negroes possessing virtues and becom-

ing ingenious; but still, what I have said, with regard

to their general character, I dare say, most people ac-

quainted with them, will agree to. †The Author of the Address gives a single example of a negro girl writing a few silly poems, to prove that the blacks are not deficient to us in understanding.

WHAT is the reason that the vast continent of Afri-

ca remains in the same state of barbarism, as if it had

been created yesterday ? It must, in all probability, be

owing to a want of genius in the people; for it has had

more chances of improving than Europe, from its vast

superiority in numbers of inhabitants. The stupidity of

the natives cannot be attributed to climate, for the

Moors, who are situated at no great distance from the

blacks, have always made a figure in history, and the

Egyptians were one of the first nations that became emi-

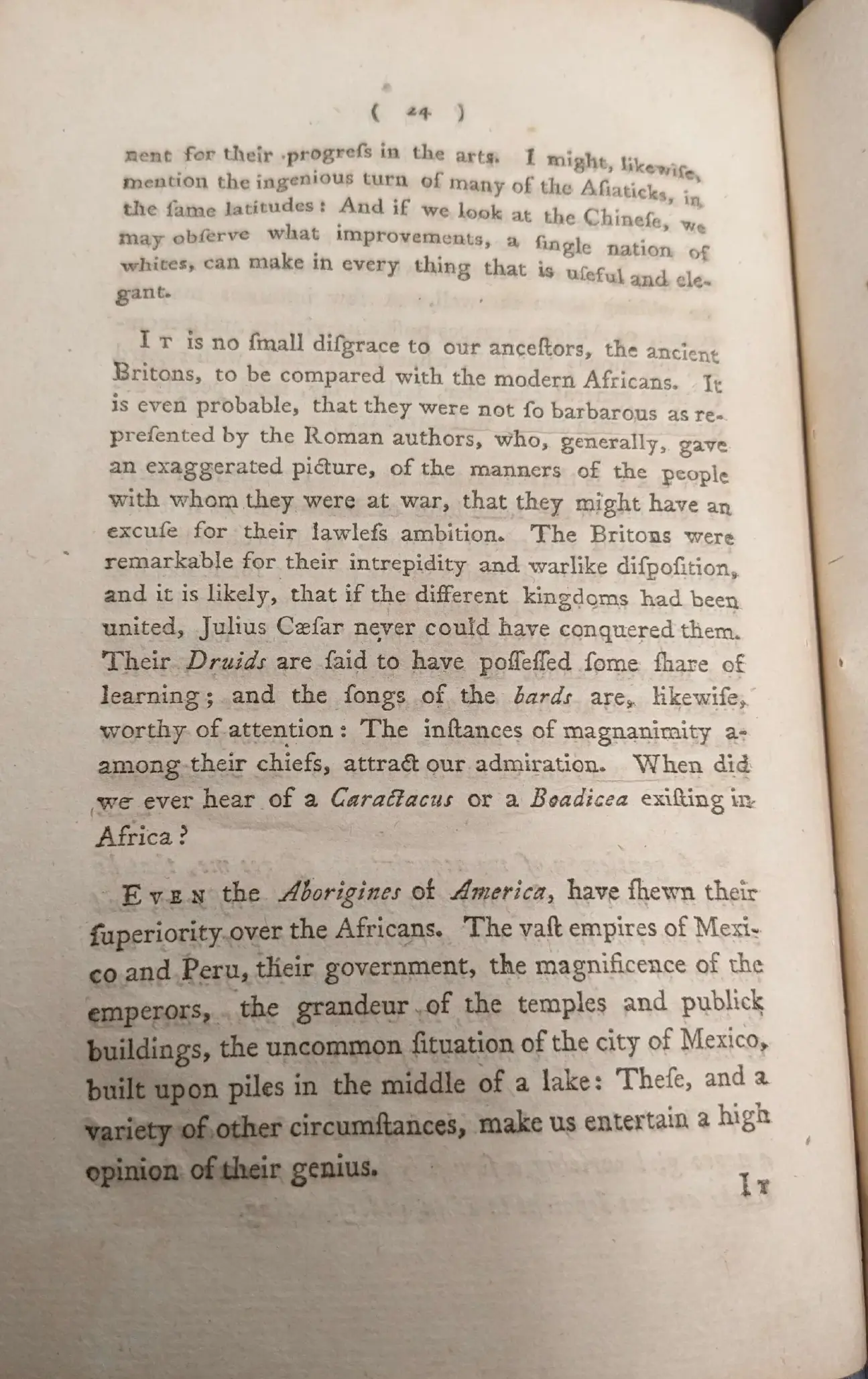

( 24 )

nent for their progress in the arts. I might, likewise,

mention the ingenious turn of many of the Asiaticks, in

the same latitudes: And if we look at the Chinese, we

may observe what improvements, a single nation of

whites, can make in every thing that is useful and ele-

gant.

IT is no small disgrace to our ancestors, the ancient

Britons, to be compared with the modern Africans. It

is even probable, that they were not so barbarous as re-

presented by the Roman authors, who, generally, gave

an exaggerated picture, of the manners of the people

with whom they were at war, that they might have an

excuse for their lawless ambition. The Britons were

remarkable for their intrepidity and warlike disposition,

and it is likely, that if the different kingdoms had been

united, Julius Cæsar never could have conquered them.

Their Druids are said to have possessed some share of

learning; and the songs of the bards are, likewise,

worthy of attention: The instances of magnanimity a-

among their chiefs, attract our admiration. When did

we ever hear of a Caractacus or a Boadicea existing in

Africa ?

EVEN the Aborigines of America, have shewn their

superiority over the Africans. The vast empires of Mexi-

co and Peru, their government, the magnificence of the

emperors, the grandeur of the temple and publick

buildings, the uncommon situation of the city of Mexico,

built upon piles in the middle of a lake: These, and a

variety of other circumstances, make us entertain a high

opinion of their genius.

(25)

IT is somewhat strange, that there is a great diffe-

rence between the negroes imported from Africa, and

those born in the West-Indies. The greatest part of the

former are to the last degree stupid, lazy, and forbid-

ding in their persons: The latter have much superior in-

tellects, and are by far more inclinable to work. They

may likewise, be distinguished at first sight, from the

former, by the superior robustness of their persons, their

vivacity of aspect, smoothness of skin, and regularity of

features. When an estate is sold, they are appraised

much higher than the natives of Africa; yet it is endea-

voured to make us believe, that negroes pine and dege-

nerate in our part of the world.

I AM little acquainted with the method of carrying

on the slave trade, and, therefore shall say little on the

subject. It appears plain, however. that slaves are

bought in the fair course of trade, and that the Europe-

ans have seldom, or never, an opportunity of carrying

them off by stealth, though they were inclinable. It is,

likewise, certain, that these creatures, by being sold to

the Europeans, are often saved from the most cruel

deaths, or more wretched slavery to their fellow barba-

rians.

I AM at a loss to know, by what authority the Au-

thor of the Address asserts, that wars were uncommon

among the negroes, till their intercourse began with

the whites. The conduct of savages in every other part of

the world, and several tribes of blacks, among whom

(26)

there is no slave trade, convinces us, that all uncivilized

nations are frequently fighting against one another.

WHEN negroes are exposed to sale, instead of being

dispirited, they often shew signs of mirth. When indivi-

duals seem attached to their relations, they are seldom

or never separated; as no person would be foolish

enough to buy a negroe that appears distressed, since

he must run no small risque of losing him.

WHEN a planter takes home a parcel of new slaves,

it is not to be imagined that he will endanger the loss of

great part of his fortune, by forcing them to work before

they are able. They are attended with the same care as

if they were infants, and many of them, who turn out well

afterwards, will not be able to do the smallest service

for above a twelvemonth. Others, though they may

have no visible disorder, in spite of every care, can ne-

ver be persuaded to work, and remain, for many years,

a dead burthen to the proprietors. Many of these use-

less negroes have been purchased by masters of vessels,

and carried to North America; by change of air they

sometimes recover, and help to confirm the idle reports

of cruel treatment in the West-Indies.

THERE is always an abundance of easy work about a

sugar plantation, for the weakly negroes, such as weed-

ing and taking care of the live stock. The employment

of the more robust is moderate, and not more severe

than the labour of peasants in other countries.

(27)

The common accusation, that the West-Indies are

obliged to have supplies from Africa, to keep up their

number is very unjust. *It is impossible to determine what quantity of negroes is purchased by the English planters for their own use, by learning the numbers imported from Africa, as the English, not only supply themselves but, likewise, in a great measure, the French, Dutch, and Spaniards. No doubt great numbers, have

been imported within these twenty or thirty years, but

that is owing to the improvements that have been car-

ried on in all the islands, not from any decrease. They

have almost doubled their quantity of produce within

the time I mention, which could not have been accom-

plished without a proportional addition of slaves. Many

estates have at present, even more than twice the num-

ber of negroes that belonged to them ten years ago.

The ceded islands have, likewise, created a vast de-

mand since the late general peace. It must be observed,

however, that if a planter settles an estate entirely with

new negroes, his gang will rather diminish? but if it

consists chiefly of Creoles, the contrary will be the case.

I SUPPOSE that many more negroes would be born in

the West-Indies, than are at present, if their increase was

not checked by the irregularities of both sexes, and their

carelessness in preserving their health. They frequently

assemble, after their work is over, and dance great

part of the night. Instead of going home they

often sleep in the open air, which exposes then to num-

berless disorders. I may add, that the misfortunes they

meet with are mostly of their own seeking.

A NEGRO may be said to have fewer cares, and less

reason to be anxious about to-morrow, than any other

( 28 )

individual of our species. A savage may be unsuccess-

ful against his enemies, and in the chace. The former

may expose him and all his family to a miserable

death, and the latter to the horrors of famine. It is a

very rare instance indeed, when the negro does not re-

ceive his usual quantity of provisions; and he is entirely

unacquainted with all the distresses attendant upon war.

The negro, it is true, cannot easily change his master,

but to make amends for this inconvenience, he enjoys the

singular advantage, over his brother in freedom, of being

attended with care during sickness, and of having the same

provision in old age, as in the days of his youth. Instead of

being oppressed to feed a large family, like the labourer

in Europe, the more children he has, the richer he be-

comes; for the moment a child is born, the parents re-

ceive the same quantity of food for its support, as if it

were a grown person ; and in case of their own death, if

they have any reflection, they will quit the world with

the certainty, of their children being brought up with

the same care they formerly experienced themselves.

I SHOULD trespass too much on the patience of my

readers, if I were to give a minute detail of the man-

ner of living of the negroes; but from what I have al-

ready mentioned, I dare say it will appear, that they

do not suffer the hardships that are so pathetically repre-

sented by many people, who are totally unacquainted

with the West-Indies.*Before this treatise was made public, I shewed it to several of my friends, now in this place, many of whom had spent a great number of years in the West-Indies, they agreed that every thing mentioned, relative to that part of the world, was just, and they are, likewise, ready to give their names if required. I repeat that self interest ( which

( 29 )

generally overpowers the most violent of our passions)

will secure them ease and plenty, though their owners

should be deaf to the calls of humanity; and when peo-

ple are assured by well attested facts, that they seldom

are destitute of both these protectors, every one must ac-

knowledge they ought to be envied, rather than pitied,

by the poor of other countries. They may be pronounced

happier than the common people of many of the arbi-

trary governments in Europe,†<em>The Polish peasants, `tis said, are sold along with an estate, in the same manner as negroes.and even several of the

peasants in Scotland and Ireland. Our happiness is in

a great measure comparative. The negroes may experi-

ence some inconveniences which their white brethren are

not exposed to, but in their turn they enjoy advantages

not known to the others; and at any rate, if it should be

granted, that they have not so great a share of the good

things of this life, as the vulgar of some other coun-

tries; yet they by no means deserve to be painted out, as

a people that endure more hardships than many of our

other fellow creatures, who are infinitely their superiors

in every thing that constitutes genius.

I SHALL take my leave of the Addresser and others

who have written in the same stile, with wishing, that

they may, for the future, employ their talents on more

useful subjects. They will find that their labours will

have a much better chance of reforming the abuses they

complain of, by offering rational proposals of improve-

ment, than by indulging themselves in such idle chimeras.

What advises the ruin of a number of individuals, can

not be called a scheme of publick utility. These gentle-

men, perhaps, think it meritorious, to give the twenti-

eth, or even fiftieth, part of their income to the poor,

( 30 )

yet they gravely desire a numerous body of British sub-

jects, to beggar themselves and families, to gratify their

caprice. All the while too, they profess humanity,

christian charity, and brotherly love. — God defend me

from these virtues, if they could provide such effects!

IF the Author of the Address were to become owner

of a West-India estate, by the death of a relation, or

some other unexpected means, can he lay his hand on

his heart, and, with a safe conscience, say that he

would instantly free all his slaves and destroy his sugar-

works? I am afraid he would hesitate, if we may judge

from the conduct of others. Many of the firmest sup-

porters of religion, in England, both clergy and laity

(whose names I could mention ) have no scruples to be

masters of West-India plantations. Until the Addresser

reduces to practice, what he points out to others, peo-

ple must suspect he writes from selfish motives, and

that he advises, what is foreign to his real opinion. I

even imagine that he may miss his aim, if he has inte-

rested views, for, though he may ingratiate himself

with many gloomy fanaticks, yet he must lose the e-

steem of men of sense, and of a rational way of thinking.

I SHALL, lastly, observe, that a person can hardly

err so grosly, as not to be able to make attonement. I

flatter myself that, upon mature reflection, the Author

of the Address, will candidly confess, that his treatise

was hastily written, without having sufficient proofs for

what he advanced, and be sorry for his ungenerous

abuse of a set of men, whom he never had an opportuni-

ty of knowing, and who, I dare say, never injured him.

FINIS.

Collections

Tags

Footnotes

- *Before this treatise was made public, I shewed it to several of my friends, now in this place, many of whom had spent a great number of years in the West-Indies, they agreed that every thing mentioned, relative to that part of the world, was just, and they are, likewise, ready to give their names if required.

- †The Author of the Address gives a single example of a negro girl writing a few silly poems, to prove that the blacks are not deficient to us in understanding.

- §If men strive and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart from her, and yet no mischief follow: he shall be surely punished, according as the woman`s husband will lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judge determine. ——— Exod. xxi. 22.

- ¶Many of the penal laws of the islands, relating to slaves, may, at first sight, appear harsh, and give an unfavourable idea of the clemency of our legislatures: but on examination, they will appear excusable and absolutely necessary to the safety and good government of the islands. The disproportion of white and black inhabitants, is there very great ; and self- preservation, that first and ruling principle of human nature, alarming our fears, has made us jealous, and perhaps severe in our threats against delinquents. Besides, if we attend to the history of our penal laws relating to slaves, I believe we shall generally find, that they took their rise from some very atrocious attempts made by the negroes, on the properties of the masters, or after some insurrection or commotion, which struck at the very being of the colonies. Under those circumstances it may very justly be supposed, that our legislatures when convened were a good deal inflamed, and might be induced for the preservation of their persons and properties, to pass many severe laws, which they might hold over their heads, to ter- [continued on pg. 19] rify and restrain them.

- †This writer talks much of slave-keeping and breaking the eighth commandment, but he certainly ought to have perused the ninth with attention, before he favoured the world with such specimens of his skill in the assassination of characters.

- *A gentleman of my acquaintance assures me, that he attended most of the sales this year at Charlestown, and only saw two instances of a reluctance at parting ; and another of my friends, who was a clerk two years in one of the first Guinea houses, in Grenada, assures me, that he never saw a single instance of the kind.

- †The Polish peasants, `tis said, are sold along with an estate, in the same manner as negroes.