Richard Ligon

A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbados (1657)

First published in 1657, Ligon’s account details the experiences of a royalist who escaped to the Caribbean island of Barbados during the English Civil War.

Introduction

Having lost much of his wealth during the English civil wars, Richard Ligon (c. 1585-1662) left England in the summer of 1647 to regain his fortune on the small Caribbean island of Barbados, one of the most valuable colonies in the Empire. Ligon, a patron to the Royalist exile Thomas Modyford, spent three years on the island working as a plantation manager before returning in 1650 following a severe bout with yellow fever. By then, the white European population on the island had increased to about 30,000, compared with 12,800 black Africans, as many planters had begun to switch from cultivating cotton and tobacco to sugarcane for export, substantially increasing labor demands. Between 1640 and 1660, English Caribbean planters had purchased about 55,000 African captives whom they claimed as slaves, and the trend only accelerated. Although most of the True & Exact History of the Island of Barbados (1657) is devoted to the development of the island’s booming sugar economy, Ligon demonstrates a keen interest in the material and religious lives of the local enslaved population as well.

Despite the relatively large and growing number of African slaves on Barbados, questions about the legality of slavery under English law and the connection between slavery and religious status remained tenuous and, increasingly, contested. In the excerpt below, Ligon advances several arguments to refute Barbadian slaveowners’ concerns about slave revolts, which they considered a serious threat to the racial hierarchy and political stability of the sugar colony. But he also comments on enslaved people’s interest in Protestant Christianity and his interaction with men such as Sambo.. How does Ligon explain Sambo’s desire to become Christian? On what grounds does his master oppose his request? And what, if anything, can his response tell us about the relationship between slavery, law, and Christianity—in Barbados and in the early English empire more broadly?

First published in 1657 in London by Humphrey Mosley, Ligon’s narrative included a new foldout map of Barbados (pictured on the right) that might have been based on an earlier drawing by John Swan from 1638. The map identifies the name and location of each of the nearly three hundred plantations, most of which were located along the leeward coast of the island. Also depicted on the map are wild hogs, hunters, and runaway slaves, as well as four churches and military fortifications near Bridgetown, the main town in Barbados. The dense forests and unfinished roads leading into the interior suggest that settlement of the island was yet to be fully completed.

Matt Fischer

Further Reading

- Amussen, Susan D. Caribbean Exchanges: Slavery and the Transformation of English Society, 1640-1700. The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Beckles, Hilary McD. White Servitude and Black Slavery in Barbados, 1627–1715. University of Tennessee Press, 1989.

- Dunn, Richard S. Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713. University of North Carolina Press, 1973.

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. “Introduction.” A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados. Hackett Publishing Company, 2011.

- Menard, Russell. Sweet Negotiations: Sugar, Slavery, and Plantation Agriculture in Early Barbados. University of Virginia Press, 2006.

- Parrish, Susan Scott. “Richard Ligon and the Atlantic Science of Commonwealths.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 67, no. 2 (April 2010): 209-248.

- Sharples, Jason T. The World That Fear Made: Slave Revolts and Conspiracy Scares in Early America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

Sources

- Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados. Illustrated with a Mapp of the island, as also the Principall Trees and Plants there, set forth in their due Proportions and Shapes, drawne out by their severall and respective scales. Together with the Ingenio that makes the Sugar, with the Plots of the severall Houses, Roomes, and other places, that are used in the whole processe of Sugar-making, [1st. ed.] (London: Humphrey Moseley, 1657), 46-58.

- Document images courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- Transcription credit: Matt Fischer, Madeline Rihn, Michael Becker, and Dylan Bails.

Cite this page

Ligon’s Map of Barbados in the True & Exact History, 1657

Original at The John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

A TRUE & EXACT

HISTORY

Of the Island of

BARBADOS.

Illustrated with a Mapp of the Island, as

also the Principall Trees and Plants there, set forth

in their due Proportions and Shapes, drawne out by

their several and respective Scales.

Together with the Ingenio that makes the Sugar, with

the Plots of the severall Houses, Roomes, and other places, that

are used in the whole processe of Sugar-making; viz. the Grinding-

room, the Boyling-room, the Filling-room, the Curing-

house, Still-house, and Furnaces;

All cut in Copper.

By RICHARD LIGON Gentleman

LONDON,

Printed for Humphrey Moseley, at the Prince`s Armes

in St. Paul`s Church-yard: 1657.

[46]

[section starts midway down page]

{Negres.} It has been accounted a strange thing, that the Negres, being more

then double the numbers of the Christians that are there, and they

accounted a bloody people, where they think they have power or ad-

vantages; and the more bloody, by how much they are more fear-

full than others: that these should not commit some horrid massacre

upon the Christians, thereby to enfranchise themselves, and become

Masters of the Iland. But there are three reasons that take away this

wonder; the one is, They are not suffered to touch or handle any wea-

pons: The other, That they are held in such awe and slavery, as they

are fearfull to appear in any daring act; and seeing the mustering of

our men, and hearing their Gun-shot, (than which nothing is more

terrible to them) their spirits are subjugated to so low a condition,

as they dare not look up to any bold attempt. Besides these, there is a

third reason, which stops all designes of that kind, and that is, They

are fetch’d from severall parts of Africa, who speake severall langua-

ges, and by that means, one of them understands not another: For,

some of them are fetch’d from Guinny and Binny, some from Cutchew,

some from Angola, and some from the River of Gambra. And in some

of these places where petty Kingdomes are, they sell their Subjects,

and such as they take in Battle, whom they make slaves; and some

mean men sell their Servants, their Children, and sometimes their

Wives; and think all good traffick, for such commodities as our Mer-

chants sends them.

When they are brought to us, the Planters buy them out of the

Ship, where they find them stark naked, and therefore cannot be de-

ceived in any outward infirmity. They choose them as they do Horses

in a Market; the strongest, youthfullest, and most beautifull, yield

the greatest prices. Thirty pound sterling is a price for the best

man Negre; and twenty five, twenty six, or twenty seven pound for

a Woman; the Children are at easier rates. And we buy them so, as

[47]

the sexes may be equall; for, if they have more men then women, the

men who are unmarried will come to their Masters, and complain,

that they cannot live without Wives, and desire him, they may have

Wives. And he tells them, that the next ship that comes, he will buy

them Wives, which satisfies them for the present; and so they expect

the good time: which the Master performing with them, the bravest

fellow is to choose first, and so in order, as they are in place; and eve-

ry one of them knowes his better, and gives him the precedence, as

Cowes do one another, in passing through a narrow gate; for, the most

of them are as neer beasts as may be, setting their souls aside. Reli-

gion they know none; yet most of them acknowledge a God, as ap-

pears by their motions and gestures; For, if one of them do another

wrong, and he cannot revenge himselfe, he looks up to Heaven for

vengeance, and holds up both his hands, as if the power must come

from thence, that must do him right. Chast they are as any people

under the Sun; for, when the men and women are together naked,

they never cast their eyes towards the parts that ought to be covered;

and those amongst us, that have Breeches and Petticoats, I never saw

so much as a kisse, or embrace, or a wanton glance with their eyes

between them. Jealous they are of their Wives, and hold it for a

great injury and scorn, if another man make the least courtship to his

Wife. And if any of their Wives have two Children at a birth, they

conclude her false to his Bed, and so no more adoe but hang her.

We had an excellent Negre in the Plantation, whose name was Macow,

and was our chiefe Musitian; a very valiant man, and was keeper of

our Plantine-groave. This Negres Wife was brought to bed of two

Children, and her Husband, as their manner is, had provided a cord

to hang her. But the Overseer finding what he was about to do, en-

formed the Master of it, who sent for Macow, to disswade him from

this cruell act, of murdering his Wife, and used all perswasions that

possibly he could, to let him see, that such double births are in Na-

ture, and that divers presidents were to be found amongst us of the

like; so that we rather praised our Wives, for their fertility, than

blamed them for their falsenesse. But this prevailed little with him,

upon whom custome had taken so deep an impression; but resolved,

the next thing he did, should be to hang her. Which when the Master

perceived, and that the ignorance of the man, should take away the

life of the woman, who was innocent of the crime her Husband con-

demned her for, told him plainly, that if he hang’d her, he himselfe

should be hang’d by her, upon the same bough; and therefore wish’d

him to consider what he did. This threatning wrought more with

him, then all the reasons of Philosophy that could be given him;

and so let her alone; but he never car’d much for her afterward, but

chose another which he lik’d better. For the Planters there deny

not a slave, that is a brave fellow, and one that has extraordinary

qualities, two or three Wives, and above that number they seldome

go: But no woman is allowed above one Husband.

At the time the wife is to be brought a bed, her husband removes

his board, (which is his bed) to another room (for many severall divi-

sions they have, in their little houses,) and none above sixe foot square)

[48]

And leaves his wife to God, and her good fortune, in the room, and

upon the board alone, and calls a neighbour to come to her, who

gives little help to her deliverie, but when the child is borne, (which

she calls her Pickaninnie) she helps to make a little fire nere her feet

and that serves instead of Possets, Broaths, and Caudles. In a fort-

night, this woman is at worke with her Pickaninny at her back, as

merry a soule as any is there: If the overseer be discreet, shee is

suffer’d to rest her selfe a little more then ordinary; but if not, shee is

compelled to doe as others doe. Times they have of suckling their

Children in the fields, and refreshing themselves; and good reason, for

they carry burdens on their backs; and yet work too. Some women,

whose Pickaninnies are three yeers old, will, as they worke at weed-

ing, which is a stooping worke, suffer the hee Pickaninnie, to sit astride

upon their backs, like St. George a horse back; and there spurre his

mother with his heeles, and sings and crowes on her backe, clapping

his hands, as if he meant to flye; which the mother is so pleas’d with,

as shee continues her painfull stooping posture, longer then she would

doe, rather than discompose her Joviall Pickaninnie of his pleasure,

so glad she is to see him merry. The worke which the women doe,

is most of it weeding, a stooping and painfull worke; at noon and night

they are call’d home by the ring of a Bell, where they have two hours

time for their repast at noone; and at night, they rest from sixe, till sixe

a Clock next morning.

On Sunday they rest, and have the whole day at their pleasure; and

the most of them use it as a day of rest and pleasure; but some of them

who will make benefit of that dayes liberty, goe where the Man-

grave trees grow, and gather the barke of which they make

ropes, which they trucke away for other Commoditie, as shirts

and drawers.

In the afternoons on Sundayes, they have their musicke, which

is of kettle drums, and those of severall fifes; upon the smallest the

best musitian playes, and other come in as Chorasses: the drum all

men know, has but one tone; and therefore varietie of tunes have little

to doe in this musick; and yet so strangely they varie their time, as ’tis

a pleasure to the most curious eares, and it was to me one of the stran-

gest noyses that ever I heard made of one tone; and if they had the

varietie of tune, which gives the greater scope in musick, as they have

of time, they would doe wonders in that Art. And if I had not faln

sicke before my comming away, at least seven months in one sickness,

I had given them some hints of tunes, which being understood,

would have serv’d as a great addition to their harmonie; for

time without tune, is not an eighth part of the science of Mu-

sick.

I found Macow very apt for it of himselfe, and one day comming

into the house, (which none of the Negroes use to doe, unlesse an Offi-

cer, as he was,) he found me playing on a Theorbo, and sinking to it

which he hearkened very attentively to; and when I had done

took the Theorbo in his hand, and strooke one string, stopping it by

degrees upon every fret, and finding the notes to varie, till it came to

the body of the instrument; and that the neerer the body of the in-

[49]

strument he stopt, the smaller or higher the sound was, which he found

was by the shortning of the string, considered with himselfe, how he

might make some triall of this experiment upon such an instrument

as he could come by; having no hope ever to have any instrument of

this kind to practise on. In a day or two after, walking in the Plan-

tine grove, to refresh me in that cool shade, and to delight my selfe

with the sight of those plants, which are so beautifull, as though they

left a fresh impression in me when I parted with them, yet upon a re-

view, something is discern’d in their beautie more then I remem-

bred at parting: which caused me to make often repair thither; I

found this Negro (whose office it was to attend there) being the keep-

er of that grove, sitting on the ground, and before him a piece of large

timber, upon which he had laid crosse, sixe Billets, and having a hand-

saw and a hatchet by him, would cut the billets by little and little,

till he had brought them to the tunes, he would fit them to; for the

shorter they were, the higher the Notes which he tryed by knocking

upon the ends of them with a sticke, which he had in his hand. When

I found him at it, I took the stick out of his hand, and tried the

sound, finding the sixe billets to have sixe distinct notes, one above a-

nother, which put me in a wonder, how he of himselfe, should with

out teaching doe so much. I then shewed him the difference between

flats and sharpes, which he presently apprehended, as between Fa, and

Mi: and he would have cut two more billets to those tunes, but I had

then no time to see it done, and so left him to his own enquiries.

I say this much to let you see that some of these people are capable of

learning Arts.

Another of another kinde of speculation I found; but more inge-

nious then he: and this man with three or foure more, were to attend

mee into the woods, to cut Church wayes, for I was imployed some-

times upon publique works; and those men were excellent Axe-men,

and because there were many gullies in the way, which were impassa-

ble, and by that means I was compell’d to make traverses, up and

down in the wood; and was by that in danger to misse of the poynt

to which I was to make my passage to the Church, and therefore was

faine to take a Compasse with me, which was a Circumferenter, to

make my traverses the more exact, and indeed without which, it

could not be done, setting up the Circumferenter, and observing the

Needle: This Negre Sambo comes to me, and seeing the needle wag,

desired to know the reason of its stirring, and whether it were alive:

I told him no, but it stood upon a poynt, and for a while it would stir,

but by and by stand still, which he observ’d and found it to be true.

The next question was, why it stood one way, & would not remove

to any other poynt, I told him that it would stand no way but North

and South, and upon that shew’d him the foure Cardinall poynts of

the compass, East, West, North, South, which he presently learnt by

heart, and promis’d me never to forget it. His last question was,

why it would stand North, I gave this reason, because of the huge

Rocks of Loadstone that were in the North part of the world, which

had a quality to draw Iron to it; and this Needle being of Iron, and

toucht with a Loadstone, it would alwaies stand that way.

[50]

This point of Philosophy was a little too hard for him, and so he

stood in a strange muse; which to put him out of it, I had him reach his

ax, and put it neer to the Compasse, and remove it about; and as he

did so, the Needle turned with it, which put him in the greatest ad-

miration that ever I saw a man, and so quite gave over his questions,

and desired me, that he might be made a Christian; for, he thought

to be a Christian, was to be endued with all those knowledges he

wanted.

I promised to do my best endeavour; and when I came home,

spoke to the Master of the Plantation, and told him, that poor Sambo

desired much to be a Christian. But his answer was, That the peo-

ple of that Iland were governed by the Lawes of England, and by

those Lawes, we could not make a Christian a Slave. I told him, my

request was far different from that, for I desired him to make a Slave

a Christian. His answer was, That it was true, there was a great

difference in that: But, being once a Christian, he could no more

account him a Slave, and so lose the hold they had of them as

Slaves, by making them Christians; and by that means should open

such a gap, as all the Planters in the Iland would curse him. So I

was struck mute, and poor Sambo kept out of the Church; as in-

genious, as honest, and as good a natur’d poor soul, as ever wore black,

or eat green.

On Sundaies in the afternoon, their Musick plaies, and to dancing

they go, the men by themselves, and the women by themselves, no

mixt dancing. Their motions are rather what they aim at, than what

they do; and by that means, transgresse the lesse upon the Sunday;

their hands having more of motion than their feet, & their heads more

than their hands. They may dance a whole day, and neer heat them-

selves; yet, now and then, one of the activest amongst them will leap

bolt upright, and fall in his place again, but without cutting a capre.

When they have danc’d an houre or two, the men fall to wrastle, (the

Musick playing all the while) and their manner of wrastling is, to

stand like two Cocks, with heads as low as their hipps; and thrusting

their heads one against another, hoping to catch one another by the

leg, which sometimes they do: But if both parties be weary, and that

they cannot get that advantage, then they raise their heads, by pres-

sing hard one against another, and so having nothing to take hold of

but their bare flesh, they close, and grasp one another about the mid-

dle, and have one another in the hug, and then a fair fall is given on

the back. And thus two or three couples of them are engaged at once,

for an houre together, the women looking on: for when the men be-

gin to wrastle, the women leave of their dancing, and come to be spe-

ctatours of the sport.

When any of them die, they dig a grave, and at evening they bury

him, clapping and wringing their hands, and making a dolefull sound

with their voyces. They are a people of a timerous and fearfull dis-

position, and consequently bloody, when they finde advantages. If

any of them commit a fault, give him present punishment, but do not

threaten him; for if you do, it is an even lay, he will go and hang him-

selfe, to avoid the punishment.

[51]

What their other opinions are in matter of Religion, I know not;

but certainly, they are not altogether of the sect of the Sadduces: For,

they believe a Resurrection, and that they shall go into their own

Country again, and have their youth renewed. And lodging their opi-

nion in their hearts, they make it an ordinary practice, upon

any great fright, or threatning of their Masters, to hang them-

selves.

But Collonell Walrond having lost three or foure of his best Negres

this way, and in a very little time, caused one of their heads to be cut

off, and set upon a pole a dozen foot high; and having done that,

caused all his Negres to come forth, and march round about this

head, and bid them look on it, whether this were not the head of such

an one that hang’d himselfe. Which they acknowledging, he then told

them, That they were in a main errour, in thinking they went into

their own Countries, after they were dead; for, this mans head was

here, as they all were witnesses of; and how was it possible, the body

could go without a head. Being convinc’d by this sad, yet lively spe-

ctacle, they changed their opinions; and after that, no more hanged

themselves.

When they are sick, there are two remedies that cure them; the

one, an outward, the other, an inward medicine. The outward me-

dicine is a thing they call Negre-oyle, and ’tis made in Barbary, yellow

it is as Bees wax, but soft as butter. When they feel themselves ill,

they call for some of that, and annoint their bodies, as their breasts,

bellies, and sides, and in two daies they are perfectly well. But this

does the greatest cures upon such, as have bruises or strains in their

bodies. The inward medicine is taken, when they find any weakness

or decay in their spirits and stomacks, and then a dram or two of kill-

devill revives and comforts them much.

I have been very strict, in observing the shapes of these people; and

for the men, they are very well timber’d, that is, broad between the

shoulders, full breasted, well filleted, and clean leg’d, and may hold

good with Albert Durers rules, who allowes twice the length of the head, to

the breadth of the shoulders; and twice the length of the face, to the

breadth of the hipps, and according to this rule these men are shap’d.

But the women not; for the same great Master of Proportions, allowes

to each woman, twice the length of the face to the breadth of the

shoulders, and twice the length of her own head to the breadth of the

hipps. And in that, these women are faulty; for I have seen very few

of them, whose hipps have been broader then their shoulders, unlesse

they have been very fat. The young Maides have ordinarily ve-

ry large breasts, which stand strutting out so hard and firm, as no lea-

ping, jumping, or stirring, will cause them to shake any more, then

the brawnes of their armes. But when they come to be old, and have

had five or six Children, their breasts hang down below their navells,

so that when they stoop at their common work of weeding, they hang

almost down to the ground, that at a distance, you would think they

had six legs: And the reason of this is, they tie the cloaths about

their Children’s backs, which comes upon their breasts, which by

pressing very hard, causes them to hang down to that length. Their

[52]

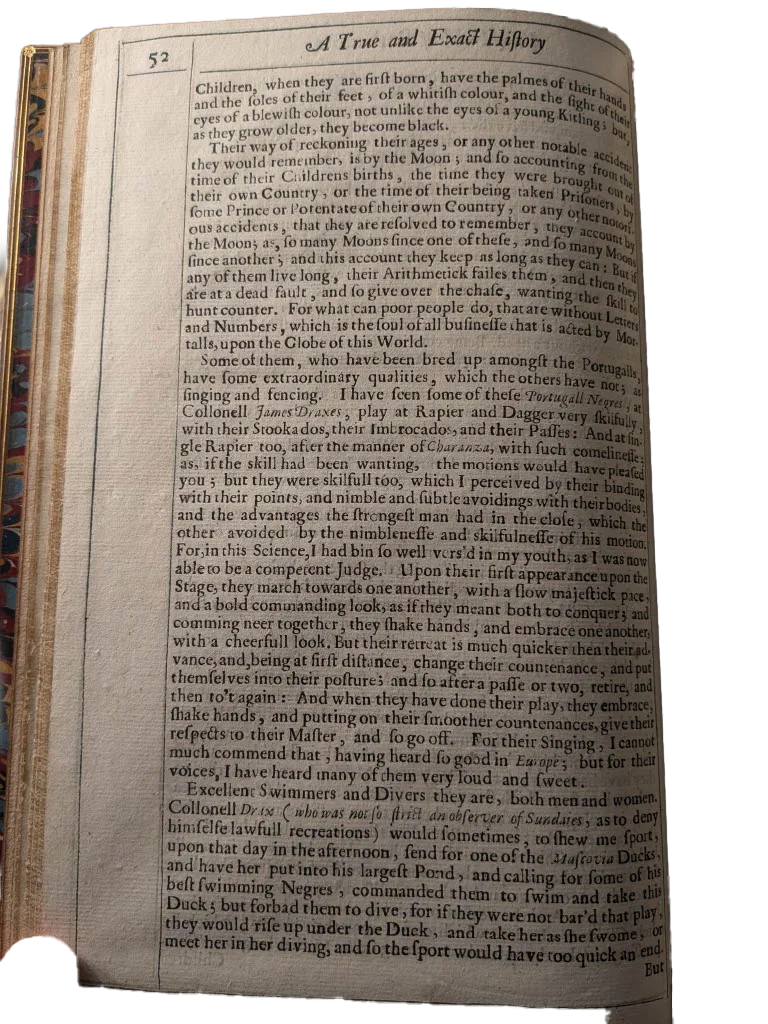

Children, when they are first born, have the palmes of their hands

and the soles of their feet, of a whitish colour, and the sight of their

eyes of a blewish colour, not unlike the eyes of a young Kitling; but,

as they grow older, they become black.

Their way of reckoning their ages, or any other notable accident

they would remember, is by the Moon; and so accounting from the

time of their Childrens births, the time they were brought out of

their own Country, or the time of their being taken Prisoners, by

some Prince or Potentate of their own Country, or any other notori-

ous accidents, that they are resolved to remember, they account by

the Moon; as, so many Moons since one of these, and so many Moons

since another; and this account they keep as long as they can: But if

any of them live long, their Arithmetick failes them, and then they

are at a dead fault, and so give over the chase, wanting the skill to

hunt counter. For what can poor people do, that are without Letters

and Numbers, which is the soul of all businesse that is acted by Mor-

talls, upon the Globe of this World.

Some of them, who have been bred up amongst the Portugalls,

have some extraordinary qualities, which the others have not; as

singing and fencing. I have seen some of these Portugall Negres, at

Collonell James Draxes, play at Rapier and Dagger very skilfully,

with their Stookados, their Imbrocados, and their Passes: And at sin-

gle Rapier too, after the manner of Charanza, with such comelinesse;

as, if the skill had been wanting, the motions would have pleased

you; but they were skilfull too, which I perceived by their binding

with their points, and nimble and subtle avoidings with their bodies,

and the advantages the strongest man had in the close, which the

other avoided by the nimblenesse and skilfulnesse of his motion.

For, in this Science, I had bin so well vers’d in my youth, as I was now

able to be a competent Judge. Upon their first appearance upon the

Stage, they march towards one another, with a slow majestick pace,

and bold commanding look, as if they meant both to conquer; and

comming neer together, they shake hands, and embrace one another,

with a cheerfull look. But their retreat is much quicker then their ad-

vance, and, being at first distance, change their countenance, and put

themselves into their posture; and so after a passe or two, retire, and

then to’t again: And when they have done their play, they embrace,

shake hands, and putting on their smoother countenances, give their

respects to their Master, and so go off. For their Singing, I cannot

much commend that, having heard so good in Europe; but for their

voices, I have heard many of them very loud and sweet.

Excellent Swimmers and Divers are they, both men and women.

Collonell Drax (who was not so strict an observer of Sundaies, as to deny

himselfe lawfull recreations) would sometimes, to shew me sport,

upon that day in the afternoon, send for one of the Muscovia Ducks,

and have her put into his largest Pond, and calling for some of his

best swimming Negres, commanded them to swim and take this

Duck; but forbad them to dive, for if they were not bar’d that play,

they would rise up under the Duck, and take her as she swome, or

meet her in her diving, and so the sport would have too quick an end.

[53]

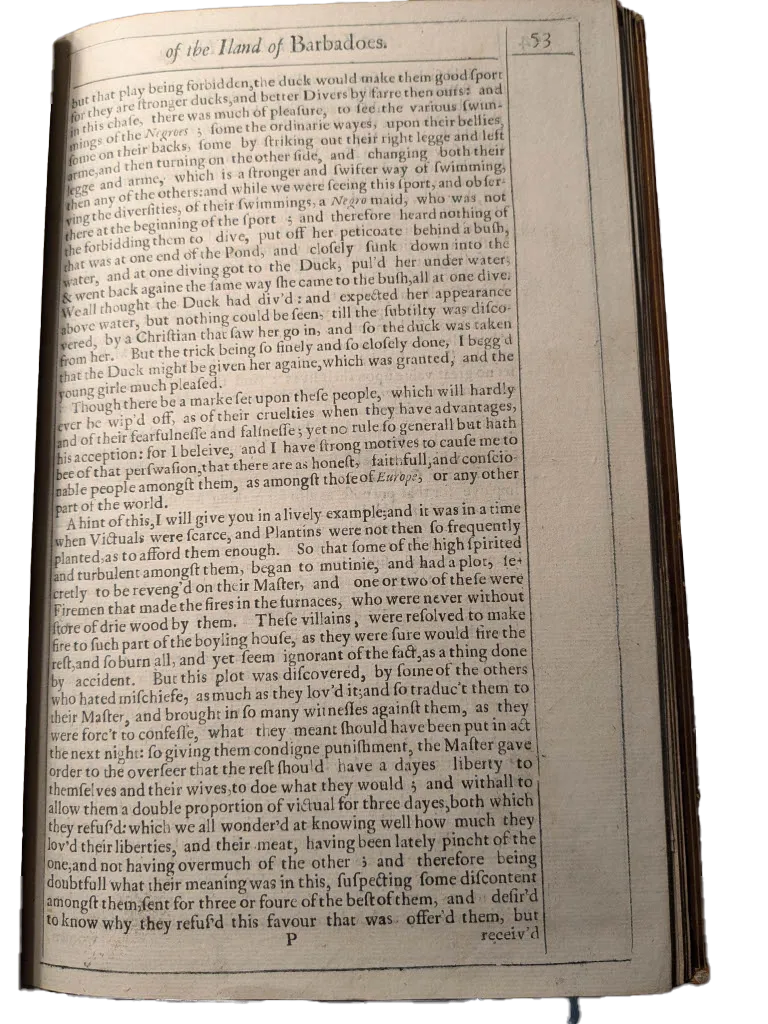

but that play being forbidden, the duck would make them good sport

for they are stronger ducks, and better Divers by farre then ours: and

in this chase, there was much of pleasure, to see the various swim-

mings of the Negroes; some the ordinarie wayes, upon their bellies,

some on their backs, some by striking out their right legge and left

arme, and then turning on the other side, and changing both their

legge and arme, which is a stronger and swifter way of swimming,

then any of the others: and while we were seeing this sport, and obser-

ving the diversities, of their swimmings, a Negro maid, who was not

there at the beginning of the sport; and therefore heard nothing of

the forbidding them to dive, put off her peticoate behind a bush,

that was at one end of the Pond, and closely sunk down into the

water, and at one diving got to the Duck, pul’d her under water,

& went back againe the same way she came to the bush, all at one dive.

We all thought the Duck had div’d: and expected her appearance

above water, but nothing could be seen, till the subtilty was disco-

vered, by a Christian that saw her go in, and so the duck was taken

from her. But the trick being so finely and so closely done, I begg’d

that the Duck might be given her againe, which was granted, and the

young girle much pleased.

Though there be a marke set upon these people, which will hardly

ever be wip’d off, as of their cruelties when they have advantages,

and of their fearfulnesse and falsnesse; yet no rule so generall but hath

his acception: for I beleive, and I have strong motives to cause me to

bee of that perswasion, that there are as honest, faithfull, and conscio-

nable people amongst them, as amongst those of Europe, or any other

part of the world.

A hint of this, I will give you in a lively example; and it was in a time

when Victuals were scarce, and Plantins were not then so frequently

planted, as to afford them enough. So that some of the high spirited

and turbulent amongst them, began to mutinie, and had a plot, se-

cretly to be reveng’d on their Master, and one or two of these were

Firemen that made the fires in the furnaces, who were never without

store of drie wood by them. These villains, were resolved to make

fire to such part of the boyling house, as they were sure would fire the

rest, and so burn all, and yet seem ignorant of the fact, as a thing done

by accident. But this plot was discovered, by some of the others

who hated mischiefe, as much as they lov’d it; and so traduc’t them to

their Master, and brought in so many witnesses against them, as they

were forc’t to confesse, what they meant should have been put in act

the next night: so giving them condigne punishment, the Master gave

order to the overseer that the rest should have a dayes liberty to

themselves and their wives, to doe what they would; and withall to

allow them a double proportion of victual for three dayes, both which

they refus’d: which we all wonder’d at knowing well how much they

lov’d their liberties, and their meat, having been lately pincht of the

one, and not having overmuch of the other; and therefore being

doubtfull what their meaning was in this, suspecting some discontent

amongst them, sent for three or foure of the best of them, and desir’d

to know why they refus’d this favour that was offer’d them, but

[54]

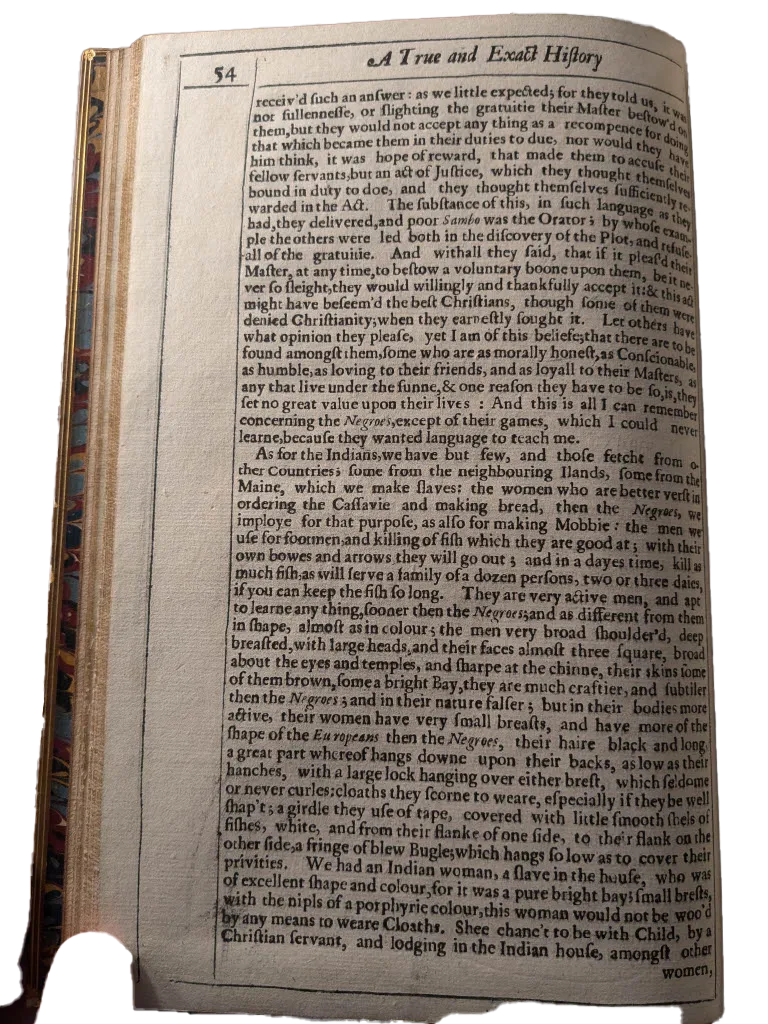

receiv’d such an answer: as we little expected; for they told us, it was

not sullennesse, or slighting the gratuitie their Master bestow’d on

them, but they would not accept any thing as a recompence for doing

that which became them in their duties to due, nor would they have

him think, it was hope of reward, that made them to accuse their

fellow servants, but an act of Justice, which they thought themselves

bound in duty to doe, and they thought themselves sufficiently re-

warded in the Act. The substance of this, in such language as they

had, they delivered, and poor Sambo was the Orator; by whose exam-

ple the others were led both in the discovery of the Plot, and refuse-

all of the gratuitie. And withall they said, that if it pleas’d their

Master, at any time, to bestow a voluntary boone upon them, be it ne-

ver so sleight, they would willingly and thankfully accept it: & this act

might have beseem’d the best Christians, though some of them were

denied Christianity; when they earnestly sought it. Let others have

what opinion they please, yet I am of this beliefe; that there are to be

found amongst them, some who are as morally honest, as Conscionable,

as humble, as loving to their friends, and as loyall to their Masters, as

any that live under the sunne, & one reason they have to be so, is, they

set no great value upon their lives: And this is all I can remember

concerning the Negroes, except of their games, which I could never

learne, because they wanted language to teach me.

As for the Indians, we have but few, and those fetcht from o-

ther Countries; some from the neighbouring Ilands, some from the

Maine, which we make slaves: the women who are better verst in

ordering the Cassavie and making bread, then the Negroes, we

imploye for that purpose, as also for making Mobbie: the men we

use for footmen, and killing of fish which they are good at; with their

own bowes and arrows they will go out; and in a dayes time, kill as

much fish, as will serve a family of a dozen persons, two or three daies,

if you can keep the fish so long. They are very active men, and apt

to learne any thing, sooner then the Negroes; and as different from them

in shape, almost as in colour; the men very broad shoulder’d, deep

breasted, with large heads, and their faces almost three square, broad

about the eyes and temples, and sharpe at the chinne, their skins some

of them brown, some a bright Bay, they are much craftier, and subtiler

then the Negroes; and in their nature falser; but in their bodies more

active, their women have very small breasts, and have more of the

shape of the Europeans then the Negroes, their haire black and long,

a great part whereof hangs downe upon their backs, as low as their

hanches, with a large lock hanging over either brest, which seldome

or never curles: cloaths they scorne to weare, especially if they be well

shap’t; a girdle they use of tape, covered with little smooth shels of

fishes, white, and from their flanke of one side, to their flank on the

other side, a fringle of blew Bugle; which hangs so low as to cover their

privities. We had an Indian woman, a slave in the house, who was

of excellent shape and colour, for it was a pure bright bay; small brests,

with the nipls of a porphyrie colour, this woman would not be woo’d

by any means to weare Cloaths. Shee chanc’t to be with Child, by a

Christian servant, and lodging in the Indian house, amongst other

[55]

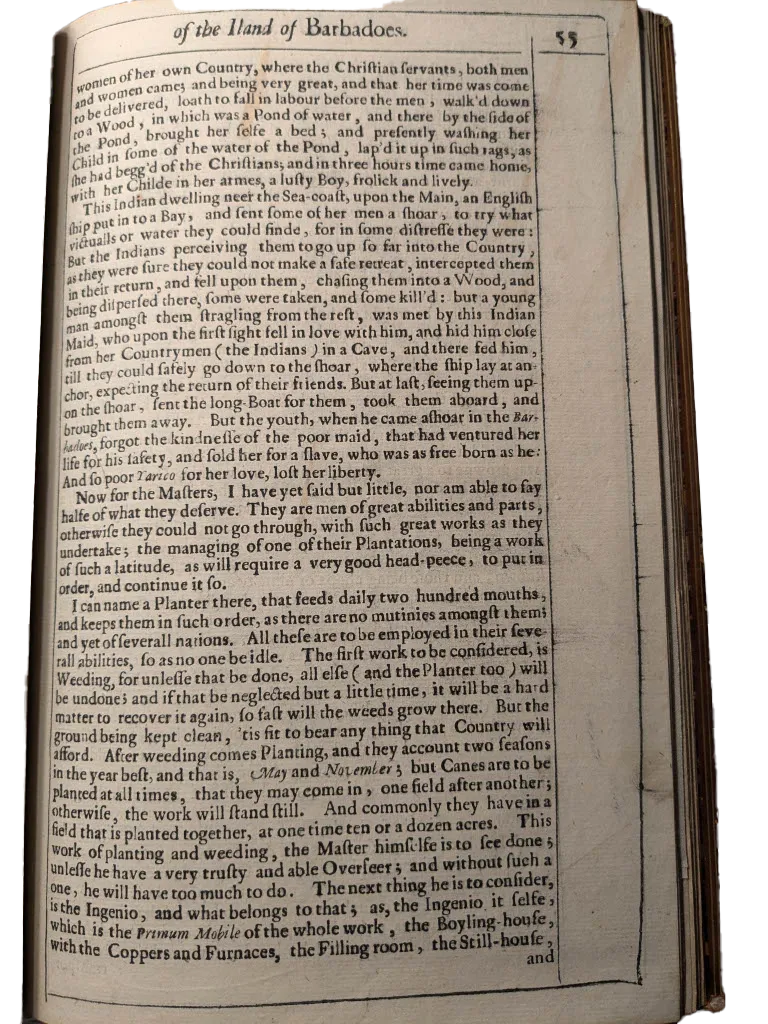

women of her own Country, where the Christian servants, both men

and women came; and being very great, and that her time was come

to be delivered, loath to fall in labour before the men, walk’d down

to a Wood, in which was a Pond of water, and there by the side of

the Pond, brought her selfe a bed; and presently washing her

Child in some of the water of the Pond, lap’d it up in such rags, as

she had begg’d of the Christians; and in three hours time came home,

with her Childe in her armes, a lusty Boy, frolick and lively.

This Indian dwelling neer the Sea-coast, upon the Main, an English

ship put in to a Bay, and sent some of her men a shoar, to try what

victualls or water they could finde, for in some distresse they were:

But the Indians perceiving them to go up so far into the Country,

as they were sure they could not make a safe retreat, intercepted them

in their return, and fell upon them, chasing them into a Wood, and

being dispersed there, some were taken, and some kill’d: but a young

man amongst them stragling from the rest, was met by this Indian

Maid, who upon the first sight fell in love with him, and hid him close

from her Countrymen (the Indians) in a Cave, and there fed him,

till they could safely go down to the shoar, where the ship lay at an-

chor, expecting the return of their friends. But at last, seeing them up-

on the shoar, sent the long-Boat for them, took them aboard, and

brought them away. But the youth, when he came ashoar in the Bar-

badoes, forgot the kindnesse of the poor maid, that had ventured her

life for his safety, and sold her for a slave, who was as free born as he:

And so poor Yarico for her love, lost her liberty.

Now for the Masters, I have yet said but little, nor am able to say

halfe of what they deserve. They are men of great abilities and parts,

otherwise they could not go through, with such great works as they

undertake; the managing of one of their Plantations, being a work

of such a latitude, as will require a very good head-peece, to put in

order, and continue it so.

I can name a Planter there, that feeds daily two hundred mouths,

and keeps them in such order, as there are no mutinies amongst them;

and yet of severall nations. All these are to be employed in their seve-

rall abilities, so as no one be idle. The first work to be considered, is

Weeding, for unlesse that be done, all else (and the Planter too) will

be undone; and if that be neglected but a little time, it will be a hard

matter to recover it again, so fast will the weeds grow there. But the

ground being kept clean, ’tis fit to bear any thing that Country will

afford. After weeding comes Planting, and they account two seasons

in the year best, and that is, May and November; but Canes are to be

planted at all times, that they may come in, one field after another;

otherwise, the work will stand still. And commonly they have in a

field that is planted together, at one time ten or a dozen acres. This

work of planting and weeding, the Master himselfe is to see done;

unlesse he have a very trusty and able Overseer; and without such a

one, he will have too much to do. The next thing he is to consider,

is the Ingenio, and what belongs to that; as, the Ingenio it selfe,

which is the Primum Mobile of the whole work, the Boyling-house,

with the Coppers and Furnaces, the Filling room, the Still-house,

[56]

and Cureing-house; and in all these, there are great casualties. If any

thing in the Rollers, as the Goudges, Sockets, Sweeps, Cogs, or Bray-

trees, be at fault, the whole work stands still; or in the Boyling-house,

if the Frame which holds the Coppers, (and is made of Clinkers,

fastned with plaister of Paris) if by the violence of the heat from the

Furnaces, these Frames crack or break, there is a stop in the work, till

that be mended. Or if any of the Coppers have a mischance, and be

burnt, a new one must presently be had, or there is a stay in the work.

Or if the mouths of the Furnaces, (which are made of a sort of stone,

which we have from England, and we call it there, high gate stone) if

that, by the violence of the fire, be softned, that it moulder away,

there must new be provided, and laid in with much art, or it will not

be. Or if the barrs of Iron, which are in the flowre of the Furnace,

when they are red hot, (as continually they are) the fire-man,

throw great shides of wood in the mouths of the Furnaces, hard

and carelessly, the weight of those logs, will bend or break those barrs,

(though strongly made) and there is no repairing them, without the

work stand still; for all these depend upon one another, as wheels in

a Clock. Or if the Stills be at fault, the kill-devill cannot be made.

But the main impediment and stop of all, is the losse of our Cattle,

and amongst them, there are such diseases, as I have known in one

Plantation, thirty that have died in two daies. And I have heard, that

a Planter, an eminent man there, that clear’d a dozen acres of ground,

and rail’d it about for pasture, with intention, as soon as the grasse

was growne to a great height, to put in his working Oxen; which ac-

cordingly he did, and in one night fifty of them dyed; so that such a

losse as this, is able to undo a Planter, that is not very well grounded.

What it is that breeds these diseases, we cannot finde, unlesse some

of the Plants have a poysonous quality; nor have we yet found out

cures for these diseases; Chickens guts being the best remedy was then

known, and those being chop’t or minc’t, and given them in a horn,

with some liquor mixt to moisten it, was thought the best remedy; yet

it recovered very few. Our Horses too have killing diseases amongst

them, and some of them have been recovered by Glisters, which we

give them in pipes, or large seringes made of wood, for the same pur-

pose. For, the common diseases, both of Cattle and Horses, are ob-

structions and bindings in their bowells; and so lingering a disease it is,

to those that recover, as they are almost worn to nothing before they

get well. So that if any of these stops continue long, or the Cattle

cannot be recruited in a reasonble time, the work is at a stand; and

by that means, the Canes grow over ripe, and will in a very short

time have their juice dried up, and will not be worth the grin-

ding.

Now to recruit these Cattle, Horses, Camells, and Assinigos, who

are all lyable to these mischances and decaies, Merchants must be con-

sulted, ships provided, and a competent Cargo of goods adventured,

to make new voyages to forraigne parts, to supply those losses; and

when that is done, the casualties at Sea are to be considered, and those

happen severall waies, either by shipwrack, piracy, or fire. A Master

of a ship, and a man accounted both able, stout, and honest, having

[57]

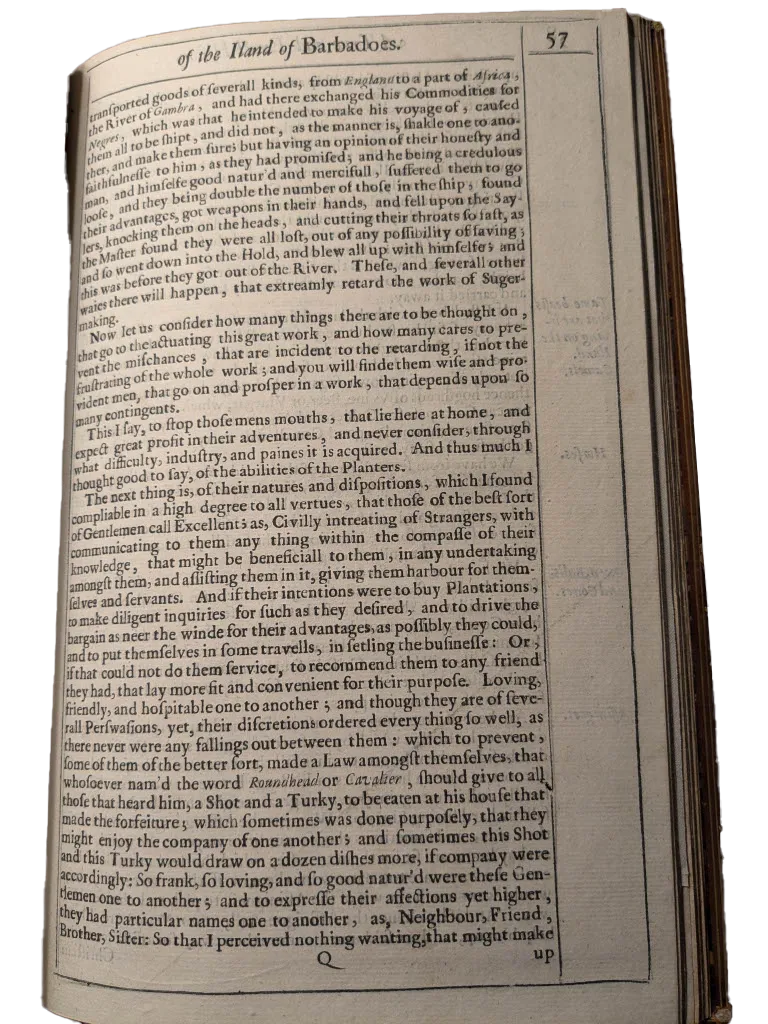

transported goods of severall kinds, from England to a part of Africa,

the River of Gambra, and had there exchanged his Commodities for

Negres, which was that he intended to make his voyage of, caused

them all to be shipt, and did not, as the manner is, shakle one to ano-

ther, and make them sure; but having an opinion of their honesty and

faithfulnesse to him, as they had promised; and he being a credulous

man, and himselfe good natur’d and mercifull, suffered them to go

loose, and they being double the number of those in the ship, found

their advantages, got weapons in their hands, and fell upon the Say-

lers, knocking them on the heads, and cutting their throats so fast, as

the Master found they were all lost, out of any possibility of saving;

and so went down into the Hold, and blew all up with himselfe; and

this was before they got out of the River. These, and severall other

waies there will happen, that extreamly retard the work of Suger-

making.

Now let us consider how many things there are to be thought on,

that go to the actuating this great work, and how many cares to pre-

vent the mischances, that are incident to the retarding, if not the

frustrating the whole work; and you will finde them wise and pro-

vident men, that go on and prosper in a work, that depends upon so

many contingents.

This I say, to stop those mens mouths, that lie here at home, and

expect great profit in their adventures, and never consider, through

what difficulty, industry, and paines it is acquired. And thus much I

thought good to say, of the abilities of the Planters.

The next thing is, of their natures and dispositions, which I found

compliable in a high degree to all vertues, that those of the best sort

of Gentlemen call Excellent; as, Civilly intreating of Strangers, with

communicating to them any thing within the compasse of their

knowledge, that might be beneficiall to them, in any undertaking

amongst them, and assisting them in it, giving them harbour for them-

selves and servants. And if their intentions were to buy Plantations,

to make diligent inquiries for such as they desired, and to drive the

bargain as neer the winde for their advantages, as possibly they could,

and to put themselves in some travells, in setling the businesse. Or,

if that could not do them service, to recommend them to any friend

they had, that lay more fit and convenient for their purpose. Loving,

friendly, and hospitable one to another; and though they are of seve-

rall Perswasions, yet, their discretions ordered every thing so well, as

there never were any fallings out between them: which to prevent,

some of them of the better sort, made a Law amongst themselves, that

whosoever nam’d the word Roundhead or Cavalier, should give to all

those that heard him, a Shot and a Turky, to be eaten at his house that

made the forfeiture; which sometimes was done purposely, that they

might enjoy the company of one another; and sometimes this Shot

and this Turky would draw on a dozen dishes more, if company were

accordingly: So frank, so loving, and so good natur’d were these Gen-

tlemen one to another; and to expresse their affections yet higher,

they had particular names one to another, as, Neighbour, Friend,

Brother, Sister: So that I perceived nothing wanting, that might make

[58]

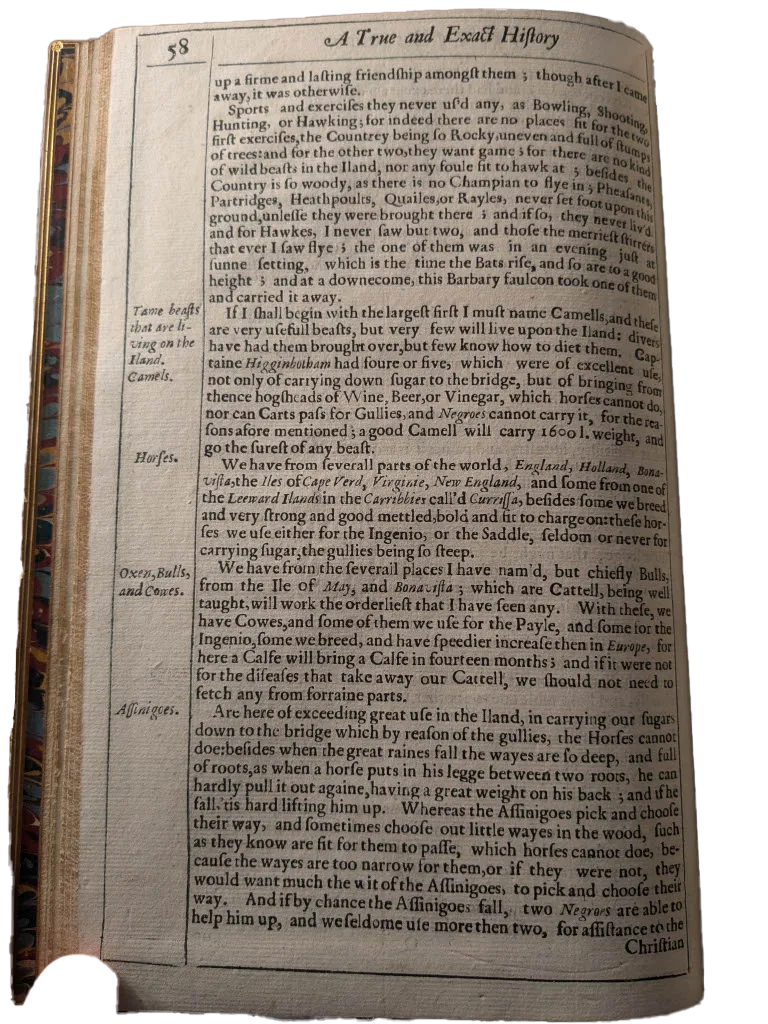

up a firme and lasting friendship amongst them; though after I came

away, it was otherwise.

Sports and exercises they never us’d any, as Bowling, Shooting,

Hunting, or Hawking; for indeed there are no places fit for the two

first exercises, the Countrey being so Rocky, uneven and full of stumps

of trees: and for the other two, they want game; for there are no kind

of wild beasts in the Iland, nor any foule fit to hawk at; besides the

Country is so woody, as there is no Champian to flye in; Pheasants,

Partridges, Heathpoults, Quailes, or Rayles, never set foot upon this

ground, unlesse they were brought there; and if so, they never liv’d

and for Hawkes, I never saw but two, and those the merriest stirrers

that ever I saw flye; the one of them was in an evening just at

sunne setting, which is the time the Bats rise, and so are to a good

height; and at a downecome, this Barbary faulcon took one of them

and carried it away.

[Section ends]