JOHN MILTON

John Milton – Eikonoklastes (1649)

Following the end of the English Civil War, the country was rattled by the destruction of the monarchy and the execution of a king. Many thought the murder of a monarch unjust. Others, like Milton, made the case for such actions.

Introduction

John Milton is well known today for his poetry, especially Paradise Lost. But in his own time, he was famous for his justification of the execution of England’s King Charles I in 1649. It begins by acknowledging that perhaps it seems unfair to write about the faults of someone now dead, but he does so in order to explore the rights of the people against their king. Below are a few excerpts to give you a flavor of this radical text. Charles I was executed by Parliament after 9 years of war, a war fought over the the rights of the king versus those of Parliament. As the son of James I (document 1), it should be clear how his arguments reflected those of his father. Many of those in Parliament used religious arguments that they should follow their own consciences and also challenged the king’s divinity. How is Milton justifying Charles I’s execution?

Holly Brewer

Further Reading

Charles I

- http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-5143?rskey=9ndZoN&result=3

- Kelsey, Sean. “The Death of Charles I.” The Historical Journal 45, no. 4 (2002): 727-54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3133526

- Kelsey, Sean. “The Trial of Charles I.” The English Historical Review 118, no. 477 (2003): 583-616. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3489287

- HOLMES, CLIVE. “THE TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF CHARLES I.” The Historical Journal 53, no. 2 (2010): 289-316. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40865689

The “Rump” Parliament

- http://bcw-project.org/church-and-state/the-commonwealth/rump-parliament

- Worden, Blair. The Rump Parliament, 1648-1653. Cambridge England: University Press, 1974.

The English Civil Wars

- Cust, Richard, and Ann Hughes. The English Civil War. Arnold Readers in History. London: Arnold, 1997.

- Ashley, Maurice. The English Civil War. Rev. and Reillustrated ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

- Ashton, Robert, and Raymond Howard Parry. The English Civil War and After, 1642-1658. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.

- Hibbert, Christopher. Cavaliers & Roundheads: The English Civil War, 1642-1649. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1993.

Sources

Document images courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC.

Citations

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

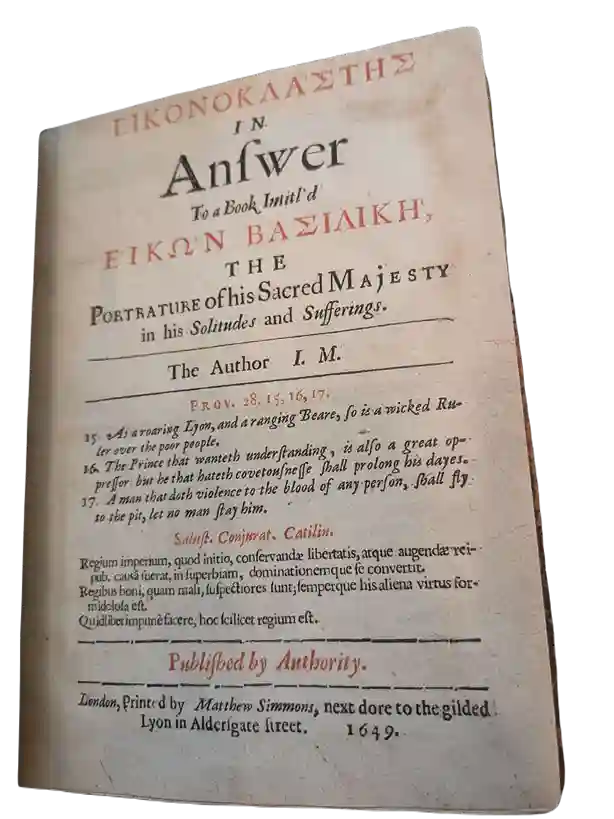

EIKONOKΛA`ΣTHΣ

IN

Answer

To a Book Intitl`d

E`IKΩ`N BAΣIΛIKH`,

THE

PORTRATURE of his Sacred MAJESTY

in his Solitudes and Sufferings.

The Author I. M.

PROV. 28. 15, 16, 17.

15. As a roaring Lyon, and a ranging Beare, so is a wicked Ru-

ler over the poor people.

16. The Prince that wanteth understanding, is also a great op-

pressor; but he that hateth covetousnesse shall prolong his dayes.

17. A man that doth violence to the blood of any person, shall fly

to the pit, let no man stay him.

Salust. Conjurat. Catilin.

Regium imperium, quod initio, conservandæ libertatis, atque augendæ rei-

pub. causâ fuerat, in superbiam, dominationemque se convertit.

Regibus boni, quam mali, suspectiores sunt; semperque his aliena virtus for-

midolosa est.

Quidlibet impunè facere, hoc scilicet regium est.

Published by Authority.

London, Printed by Matthew Simmons, next dore to the gilded

Lyon in Aldersgate street. […] 1649.

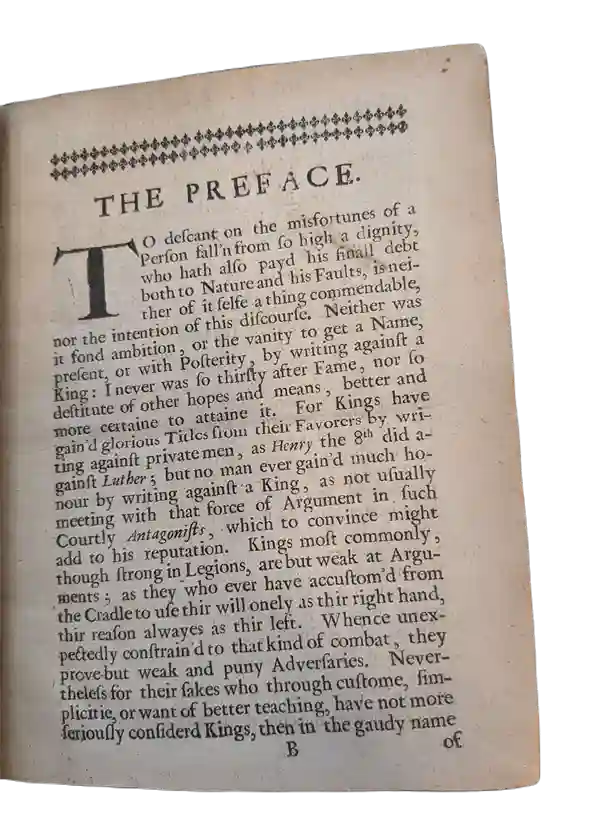

THE PREFACE.

TO descant on the misfortunes of a

Person fall’n from so high a dignity,

who hath also payd his finall debt

both to Nature and his Faults, is nei-

ther of it selfe a thing commendable,

nor the intention of this discourse. Neither was

it fond ambition, or the vanity to get a Name,

present, or with Posterity, by writing against a

King: I never was so thirsty after Fame, nor so

destitute of other hopes and means, better and

more certaine to attaine it. For Kings have

gain’d glorious Titles from their Favorers by wri-

ting against private men, as Henry the 8th did a-

gainst Luther; but no man ever gain’d much ho-

nour by writing against a King, as not usually

meeting with that force of Argument in such

Courtly Antagonists, which to convince might

add to his reputation. Kings most commonly,

though strong in Legions, are but weak at Argu-

ments; as they who ever have accustom’d from

the Cradle to use thir will onely as thir right hand,

thir reason alwayes as thir left. Whence unex-

pectedly constrain’d to that kind of combat, they

prove but weak and puny Adversaries. Never-

theless for their sakes who through custome, sim-

plicitie, or want of better teaching, have not more

seriously considerd Kings, then in the gaudy name

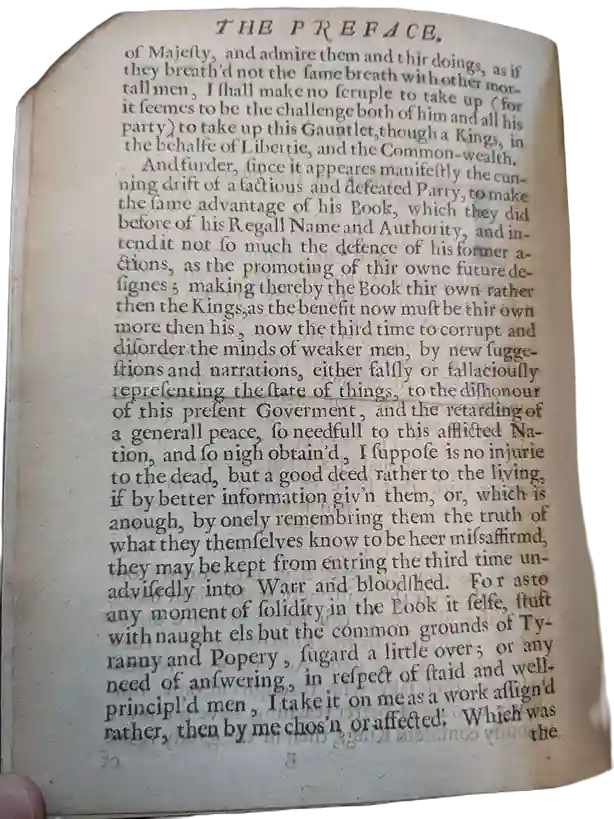

of Majesty, and admire them and thir doings, as if

they breath’d not the same breath with other mor-

tall men, I shall make no scruple to take up (for

it seemes to be the challenge both of him and all his

party) to take up this Gauntlet, though a Kings, in

the behalfe of Libertie, and the Common-wealth.

And furder, since it appeares manifestly the cun-

ning drift of a factious and defeated Party, to make

the same advantage of his Book, which they did

before of his Regall Name and Authority, and in-

tend it not so much the defence of his former a-

ctions, as the promoting of thir owne future de-

signes; making thereby the Book thir own rather

then the Kings, as the benefit now must be thir own

more then his, now the third time to corrupt and

disorder the minds of weaker men, by new sugge-

stions and narrations, either falsly or fallaciously

representing the state of things, to the dishonour

of this present Goverment, and the retarding of

a generall peace, so needfull to this afflicated Na-

tion, and so nigh obtain’d, I suppose is no injurie

to the dead, but a good deed rather to the living,

if by better information giv’n them, or, which is

anough, by onely remembring them the truth of

what they themselves know to be heer misaffirmd,

they may be kept from entring the third time un-

advisedly into Warr and bloodshed. For as to

any moment of solidity in the Book it selfe, stuft

with naught els but the common grounds of Ty-

ranny and Popery, sugard a little over; or any

need of answering, in respect of staid and well-

principl’d men, I take it on me as a work assign’d

rather, then by me chos’n or affected. Which was

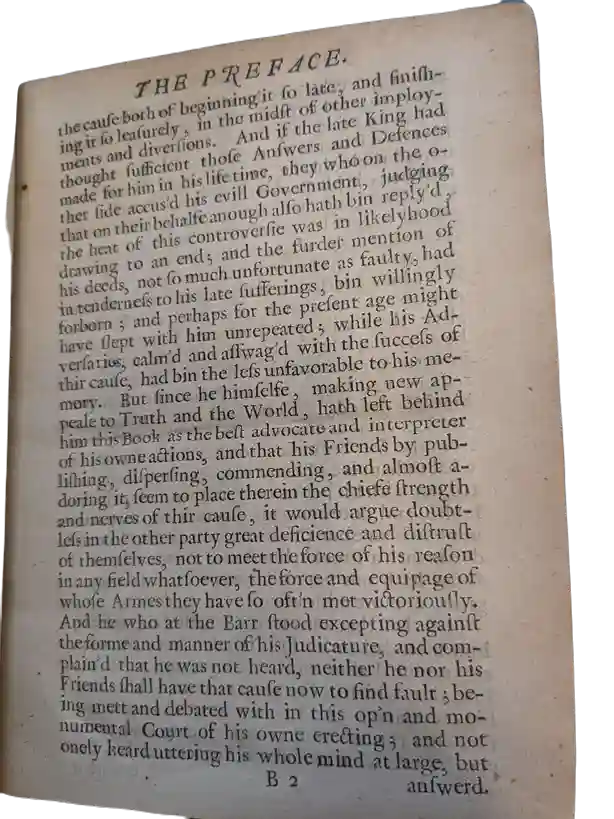

the cause both of beginning it so late, and finish-

ing it so leasurely, in the midst of other imploy-

ments and diversions. And if the late King had

thought sufficient those Answers and Defences

made for him in his life time, they who on the o-

ther side accus’d his evill Government, judging

that on their behalfe anough also hath bin reply’d,

the heat of this controversie was in likelyhood

drawing to an end; and the furder mention of

his deeds, not so much unfortunate as faulty, had

in tenderness to his late sufferings, bin willingly

forborn; and perhaps for the present age might

have slept with him unrepeated; while his Ad-

versaries, calm’d and asswag’d with the success of

thir cause, had bin the less unfavorable to his me-

mory. But since he himselfe, making new ap-

peale to Truth and the World, hath left behind

him this Book as the best advocate and interpreter

of his owne actions, and that his Friends by pub-

lishing, dispersing, commending, and almost a-

doring it, seem to place therein the chiefe strength

and nerves of thir cause, it would argue doubt-

less in the other party great deficience and distrust

of themselves, not to meet the force of his reason

in any field whatsoever, the force and equipage of

whose Armes they have so oft’n met victoriously.

And he who at the Barr stood excepting against

the forme and manner of his Judicature, and com-

plain’d that he was not heard, neither he nor his

Friends shall have that cause now to find fault; be-

ing mett and debated with in this op’n and mo-

numental Court of his owne erecting; and not

onely heard uttering his whole mind at large, but

answer’d. Which to doe effectually, if it be ne-

cessary that to his Book nothing the more respect

be had for being his, they of his owne Party can

have no just reason to exclaime. For it were too

unreasonable that he, because dead, should have

the liberty in his Booke to speake all evill of the

Parlament; and they, because living, should be ex-

pected to have less freedome, or any for them, to

speake home the plaine truth of a full and perti-

nent reply. As he, to acquitt himselfe, hath not

spar’d his Adversaries, to load them with all sorts

of blame and accusation, so to him, as in his Book

alive, there will be us’d no more Courtship then

he uses; but what is properly his owne guilt, not

imputed any more to evill Counsellors (a Ce-

remony us’d longer by the Parlament then hee

himselfe desir’d) shall be layd heer without cir-

cumlocutions at his owne dore. That they who

from the first beginning, or but now of late, by

what unhappiness I know not, are so much affatua-

ted, not with his person only, but with his palpable

faults, and dote upon his deformities, may have

none to blame but thir owne folly, if they live and

dye in such a strook’n blindness, as next to that of

Sodom hath not happ’nd to any sort of men more

gross, or more misleading.

First then that some men (whether this were by

him intended or by his Friends) have by policy

accomplish’d after death that revenge upon thir

Enemies, which in life they were not able, hath

bin oft related. And among other examples wee

find that the last Will of Cæsar being read to the

people, and what bounteous Legacies he had be-

queath’d them, wrought more in that Vulgar au-

dience to the avenging of his death, then all the

art he could ever use, to win thir favor in his life-

time. And how much their intent, who publish’d

these overlate Apologies and Meditations of the

dead King, drives to the same end of stirring up

the people to bring him that honour, that affecti-

on, and by consequence, that revenge to his dead

Corps, which he himselfe living could never gain

to his Person, it appeares both by the conceited

portraiture before his Book, drawn out to the

full measure of a Masking Scene, and sett there to

catch fools and silly gazers, and by those Latin

words after the end, Vota dabunt quæ Bella negarunt,

intimating, that what hee could not compass by

Warr, hee should atchieve by his Meditations.

For in words which admitt of various sence, the

libertie is ours to choose that interpretation which

may best mind us of what our restless enemies en-

deavor, and what we are timely to prevent. And

heer may be well observ’d the loose and negligent

curiosity of those who took upon them to adorn

the setting out of this Booke: for though the

Picture sett in Front would Martyr him and

Saint him to befoole the people, yet the Latin

Motto in the end, which they understand not,

leaves him, as it were, a politic contriver to bring

about that interest by faire and plausible words,

which the force of Armes deny’d him. But quaint

Emblems and devices begg’d from the olde Pa-

geantry of some Twelfe-nights entertainment at

Whitehall, will doe but ill to make a Saint or Mar-

tyr: and if the People resolve to take him Sainted

at the rate of such a Canonizing, I shall suspect

their Calendar more then the Gregorian. In one

thing I must commend his op’nness who gave the

Title to this Book, Εικων Βασιλικη, that is to say, The

Kings Image; and by the Shrine he dresses out for

him, certainly, would have the people come and

worship him. For which reason this Answer also

is intitl’d, Iconoclastes, the famous Surname of ma-

ny Greek Emperors, who in thir zeal to the com-

mand of God, after long tradition of Idolatry in

the Church, tooke courage and broke all su-

perstitious Images to peeces. But the people, ex-

orbitant and excessive in all thir motions, are prone

ofttimes not to a religious onely, but to a civil

kind of Idolatry, in Idolizing thir Kings; though

never more mistak’n in the object of thir worship;

heretofore being wont to repute for Saints, those

faithfull and courageous Barons, who lost thir

lives in the Field, making glorious Warr against

Tyrants for the common Liberty; as Simon de Mom-

fort, Earle of Leicester, against Henry the third;

Thomas Plantagenet Earle of Lancaster, against Edward

the second. But now with a besotted and degene-

rate baseness of spirit, except some few, who yet

retaine in them the old English fortitude and love

of freedome, and have testifi’d it by thir match-

less deeds, the rest, imbastardiz’d from the ancient

nobleness of thir Ancestors, are ready to fall flatt

and give adoration to the Image and memory of

this Man, who hath offer’d at more cunning

fetches to undermine our Liberties, and putt

Tyranny into an Art, then any Brittish King be-

fore him. Which low dejection and debasement

of mind in the people, I must confess I cannot wil-

lingly ascribe to the naturall disposition of an En-

glishman, but rather to two other causes. First to

the Prelats and thir fellow-teachers, though of

another Name and Sect, whose Pulpit-stuffe,

both first and last, hath bin the Doctrin and per-

petuall infusion of servility and wretchedness to

all thir hearers; and thir lives the type of world-

liness and hypocrisie, without the least true pat-

tern of vertue, righteousness, or selfe-denyall in

thir whole practice. I attribute it next to the

factious inclination of most men divided from the

public by severall ends and humors of thir owne.

At first no man less belov’d, no man more gene-

rally condemn’d then was the King; from the

time that it became his custom to breake Parla-

ments at home, and either wilfully or weakly to

betray Protestants abroad, to the beginning of

these Combustions. All men inveigh’d against him,

all men, except Court-vassals, oppos’d him and his

Tyrannicall proceedings; the cry was universall;

and this full Parlament was at first unanimous in

thir dislike and Protestation against his evill Go-

verment. But when they who sought themselves

and not the Public, began to doubt that all of

them could not by one and the same way attain to

thir ambitious purposes, then was the King, or

his Name at least, as a fit property, first made use of,

his doings made the best of, and by degrees justi-

fi’d: Which begot him such a party, as after ma-

ny wiles and struglings with his inward feares,

imbold’n’d him at length to sett up his Standard

against the Parlament. When as before that time,

all his adherents, consisting most of dissolute

Swordmen and Suburb roysters, hardly amounted

to the making up of one ragged regiment strong

anough to assault the unarmed house of Commons.

After which attempt seconded by a tedious and

bloody warr on his subjects, wherein he hath so

farr exceeded those his arbitrary violences in time

of peace, they who before hated him for his high

misgoverment, nay, fought against him with dis-

play’d banners in the feild, now applaud him and

extoll him for the wisest and most religious Prince

that liv’d. By so strange a method amongst the

mad multitude is a sudden reputation won, of wis-

dome by wilfullness and suttle shifts, of goodness

by multiplying evill, of pietie by endeavouring to

root out true religion.

But it is evident that the cheife of his adherents

never lov’d him, never honourd either him or his

cause, but as they took him to set a face upon

thir own malignant designes; nor bemoan his loss

at all, but the loss of their own aspiring hopes:

Like those captive women whome the Poet notes

in his Iliad, to have bewaild the death of Patroclus

in outward show, but indeed their own condition.

Πάτροκλον πρόφασιν, σφῶν δ᾿ αὐτῶν κήδε᾿ ἑκάστη.

Hom. Iliad. τ.

And it needs must be ridiculous to any judge-

ment uninthrall’d, that Cavaleirs they who in other matters

express so little feare either of God or man, should

in this one particular outstripp all precisianism

with thir scruples and cases, and fill mens ears

continually with the noise of thir conscientious

Loyalty and Allegeance to the King, Rebels in the

mean while to God in all thir actions beside: much

less that they whose profess’d Loyalty and Alle-

geance led them to direct Armes against the Kings

Person, and thought him nothing violated by

the Sword of Hostility drawn by them against

him, should now in earnest thinke him violated

by the unsparing Sword of Justice, which un-

doubtedly so much the less in vaine shee beares a-

mong Men, by how much greater and in highest

place the offender. Els Justice, whether moral

or politicall, were not Justice, but a fals counter-

fet of that impartial and Godlike vertue. The

onely griefe is, that the head was not strook off

to the best advantage and commodity of [Presbutrions] them

that held it by the haire: Which observation,

though made by a Common Enemie, may for the

truth of it heerafter become a Proverb. But as

to the Author of these Soliloquies, whether it

were the late King, as is Vulgarly beleev’d, or any

secret Coadjutor, and some stick not to name him,

it can add nothing, nor shall take from the weight,

if any be, of reason which he brings. But alle-

gations, not reasons are the maine Contents of

this Book; and need no more then other contra-

ry allegations to lay the question before all Men

in an eev’n ballance; though it were suppos’d

that the Testimony of one man in his own cause

affirming, could be of any moment to bring in

doubt the autority of a Parlament denying. But

if these his faire spok’n words shall be heer fairely

confronted and laid parallel to his own farr dif-

fering deeds, manifest and visible to the whole

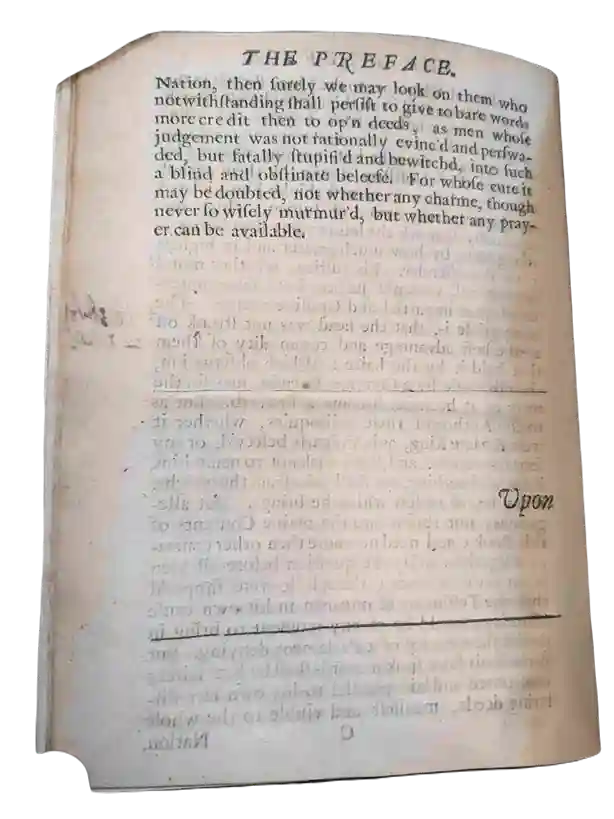

Nation, then surely we may look on them who

notwithstanding shall persist to give to bare words

more credit then to op’n deeds, as men whose

judgement was not rationally evinc’d and perswa-

ded, but fatally stupifi’d and bewitchd, into such

a blind and obstinate beleefe. For whose cure it

may be doubted, not whether any charme, though

never so wisely murmur’d, but whether any pray-

er can be available.

VI. Upon His Retirement from

Westminster.

THE Simily wherwith hee beginns I

was about to have found fault with,

as in a garb somwhat more Poeticall

then for a Statist: but meeting with

many straines of like dress in other of

his Essaies, and hearing him reported a more diligent

reader of Poets, then of Politicians, I begun to think

that the whole Book might perhaps be intended a

peece of Poetrie. The words are good, the fiction

smooth and cleanly; there wanted onely Rime, and

that, they say, is bestow’d upon it lately. But to

the Argument.

I stay`d at White Hall till I was driv`n away by

shame more then feare. I retract not what I thought

of the fiction, yet heer, I must confess, it lies too

op’n. In his Messages, and Declarations, nay in

the whole Chapter next but one before this, hee

affirmes that The danger, wherein his Wife, his Chil-

dren, and his owne Person were by those Tumults,

was the maine cause that drove him from White Hall,

and appeales to God as witness: he affirmes heer

that it was shame more then feare. And Digby,

who knew his mind as well as any, tells his

new-listed Guard, That the principall cause of his

Majesties going thence, was to save them from being

trodd in the dirt. From whence we may discerne

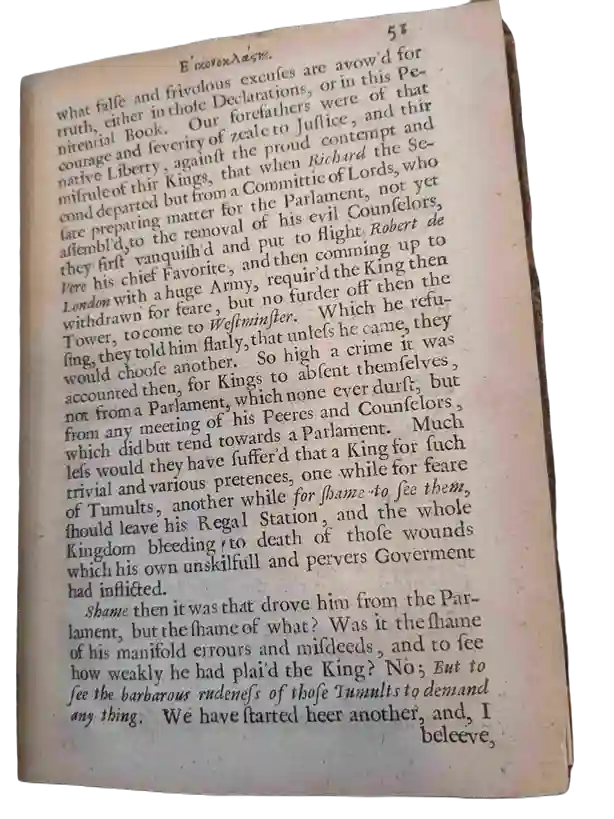

what false and frivolous excuses are avow’d for

truth, either in those Declarations, or in this Pe-

nitential Book. Our forefathers were of that

courage and severity of zeale to Justice, and thir

native Liberty, against the proud contempt and

misrule of thir Kings, that when Richard the Se-

cond departed but from a Committie of Lords, who

sate preparing matter for the Parlament, not yet

assembl’d, to the removal of his evil Counselors,

they first vanquish’d and put to flight Robert de

Vere his chief Favorite, and then comming up to

London with a huge Army, requir’d the King then

withdrawn for feare, but no furder off then the

Tower, to come to Westminster. Which he refu-

sing, they told him flatly, that unless he came, they

would choose another. So high a crime it was

accounted then, for Kings to absent themselves,

not from a Parlament, which none ever durst, but

from any meeting of his Peeres and Counselors,

which did but tend towards a Parlament. Much

less would they have suffer’d that a King for such

trivial and various pretences, one while for feare

of Tumults, another while for shame to see them,

should leave his Regal Station, and the whole

Kingdom bleeding to death of those wounds

which his own unskilfull and pervers Goverment

had inflicted.

Shame then it was that drove him from the Par-

lament, but the shame of what? Was it the shame

of his manifold errours and misdeeds, and to see

how weakly he had plai’d the King? No; But to

see the barbarous rudeness of those Tumults to demand

any thing. We have started heer another, and, I

beleeve, the truest cause of his deserting the Par-

lament. The worst and strangest of that Any thing

which the people then demanded, was but the un-

lording of Bishops, and expelling them the House,

and the reducing of Church-Discipline to a con-

formity with other Protestant Churches: this was

the Barbarism of those Tumults; and that he might

avoid the granting of those honest and pious de-

mands, as well demanded by the Parlament as the

People, for this very cause, more then for feare,

by his own confession heer, he left the City; and

in a most tempestuous season forsook the Helme,

and steerage of the Common-wealth. This was

that terrible Any thing from which his Conscience

and his Reason chose to run rather then not deny.

To be importun’d the removing of evil Counse-

lors, and other greevances in Church and State,

was to him an intollerable oppression. If the Peo-

ples demanding were so burd’nsome to him, what

was his deniall and delay of Justice to them?

But as the demands of his People were to him

a burd’n and oppression, so was the advice of his

Parlament esteem’d a bondage; Whose agreeing Votes,

as he affirmes, were not by any Law or reason conclu-

sive to his judgement. For the Law, it ordaines a

Parlament to advise him in his great affaires; but

if it ordaine also that the single judgement of a

King shall out-ballance all the wisdom of his Par-

lament, it ordaines that which frustrats the end

of its own ordaining. For where the Kings judge-

ment may dissent, to the destruction, as it may

happ’n, both of himself and the Kingdom, there

advice, and no furder, is a most insufficient, and

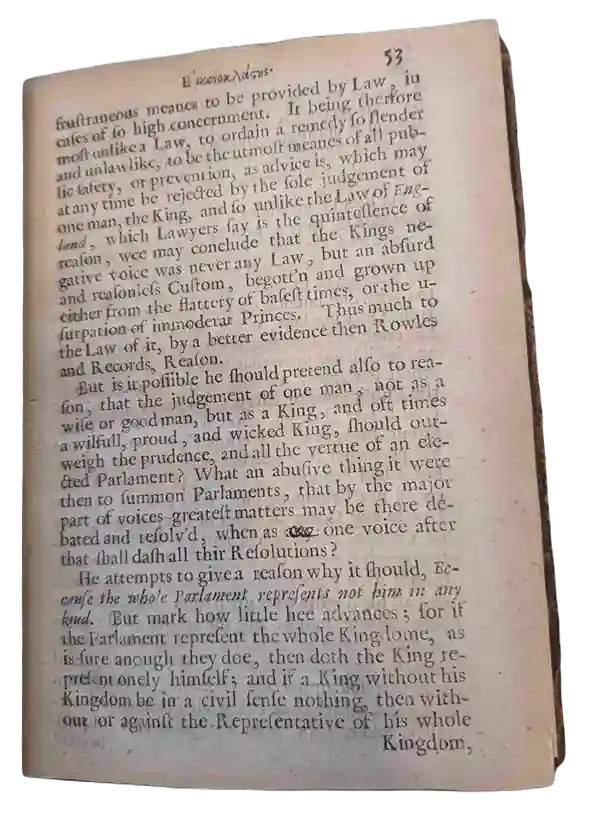

frustraneous meanes to be provided by Law, in

case of so high concernment. It being therfore

most unlike a Law, to ordain a remedy so slender

and unlawlike, to be the utmost meanes of all pub-

lic safety, or prevention, as advice is, which may

at any time be rejected by the sole judgement of

one man, the King, and so unlike the Law of Eng-

land, which Lawyers says is the quintessence of

reason, wee may conclude that the Kings ne-

gative voice was never any Law, but an absurd

and reasonless Custom, begott’n and grown up

either from the flattery of basest times, or the u-

surpation of immoderat Princes. Thus much to

the Law of it, by a better evidence then Rowles

and Records, Reason.

But is it possible he should pretend also to rea-

son, that the judgement of one man, not as a

wise or good man, but as a King, and oft times

a wilfull, proud, and wicked King, should out-

weigh the prudence, and all the vertue of an ele-

cted Parlament? What an abusive thing it were

then to summon Parlaments, that by the major

part of voices greatest matters may be there de-

bated and resolv’d, when as any one voice after

that shall dash all thir Resolutions?

He attempts to give a reason why it should, Be-

cause the whole Parlament represents not him in any

kind. But mark how little hee advances; for if

the Parlament represent the whole Kingdome, as

is sure anough they doe, then doth the King re-

present onely himself; and if a King without his

Kingdom be in a civil sense nothing, then with-

out or against the Representative of his whole

Kingdom hee himself represents nothing, and

by consequence his judgement and his negative is

as good as nothing; and though we should allow

him to be something, yet not equal, or comparable

to the whole Kingdom, and so neither to them

that represent it.

Yet heer he maintaines To be no furder bound to

agree with the Votes of both Houses, then he sees them

to agree with the will of God, with his just Rights as

a King, and the generall good of his People. As to

the freedom of his agreeing or not agreeing, limi-

ted with due bounds, no man reprehends it; this

is the Question heer, or the Miracle rather, why

his onely not agreeing should lay a negative barr

and inhibition upon that which is agreed to by a

whole Parlament, though never so conducing to

the Public good or safety. To know the will of

God better then his whole Kingdome, Whence

should he have it? Certainly Court-breeding and

his perpetual conversation with Flatterers, was

but a bad Schoole. To judge of his own Rights

could not belong to him, who had no right by

Law in any Court to judge of so much as Fellony

or Treason, being held a party in both these Ca-

ses, much more in this; and his Rights however

should give place to the general good, for which

end all his Rights were giv’n him. Lastly to sup-

pose a clearer insight and discerning of the gene-

ral good, allotted to his own singular judgement,

then to the Parlament and all the People, and

from that self-opinion of discerning, to deny them

that good which they being all Freemen seek ear-

nestly, and call for, is an arrogance and iniquity

beyond imagination rude and unreasonable: they

undoubtedly having most autoritie to judge of the

public good, who for that purpose are chos’n out,

and sent by the People to advise him. And if it

may be in him to see oft the major part of them not

in the right, had it not bin more his modestie to

have doubted their seeing him more oft’n in the

wrong?

Hee passes to another reason of his denialls, Be-

cause of some mens hydropic unsatiableness, and thirst

of asking, the more they drank, whom no fountaine of

regall bountie was able to overcome. A comparison

more properly bestow’d on those that came to guz-

zle in his Wine-cellar, then on a freeborn People

that came to claime in Parlament thir Rights and

Liberties, which a King ought therfore to grant,

because of right demanded; not to deny them for

feare his bounty should be exhaust, which in these

demands (to continue the same Metaphor) was

not so much as Broach’d; it being his duty, not his

bounty to grant these things.

Putting off the Courtier he now puts on the

Philosopher, and sententiously disputes to this

effect, That reason ought to be us`d to men, force and

terror to Beasts; that he deserves to be a slave who cap-

tivates the rationall soverantie of his soule, and liber-

ty of his will to compulsion; that he would not forfeit

that freedome which cannot be deni’d him, as a King,

because it belongs to him as a Man and a Christian,

though to preserve his Kingdom, but rather dye enjoy-

ing the Empire of his soule, then live in such a vassalage

as not to use his reason and conscience to like or dislike

as a King. Which words, of themselves, as farr as

they are sense, good and Philosophical, yet in

the mouth of him who to engross this common li-

bertie to himself, would tred down all other men

into the condition of Slaves and Beasts, they quite

loose thir commendation. He confesses a rational

sovrantie of soule, and freedom of will in every

man, and yet with an implicit repugnancy would

have his reason the sovran of that sovranty, and

would captivate and make useless that natural

freedom of will in all other men but himself. But

them that yeeld him this obedience he so well re-

wards, as to pronounce them worthy to be Slaves.

They who have lost all to be his Subjects, may

stoop and take up the reward. What that freedom

is, which cannot be deni`d him as a King, because it be-

longs to him as a Man, and a Christian, I understand

not. If it be his negative voice, it concludes all men

who have not such a negative as his against a whole

Parlament, to be neither Men, nor Christians: and

what was he himself then, all this while that we

deni’d it him as a King? Will hee say that

hee enjoy’d within himselfe the less freedom for

that? Might not he, both as a Man and as a Chri-

stian have raignd within himselfe, in full sovranty

of soule, no man repining, but that his outward

and imperious will must invade the civil Liberties

of a Nation? Did wee therfore not permit him

to use his reason or his conscience, not permitting

him to bereave us the use of ours? And might not

he have enjoy’d both, as a King, governing us as

Free men by what Laws wee our selves would be

govern’d? It was not the inward use of his rea-

son and his conscience that would content him,

but to use them both as a Law over all his Sub-

jects, in whatever he declar`d as a King to like or dis-

like. Which use of reason, most reasonless and un-

conscionable, is the utmost that any Tyrant ever

pretended over his Vassals.

In all wise Nations the Legislative power, and

the judicial execution of that power have bin most

commonly distinct, and in several hands: but

yet the former supreme, the other subordinat. If

then the King be only set up to execute the Law,

which is indeed the highest of his Office, he ought

no more to make or forbidd the making of any law

agreed upon in Parlament; then other inferior

Judges, who are his Deputies. Neither can hee

more reject a Law offerd him by the Commons,

then he can new make a Law which they reject.

And yet the more to credit and uphold his cause,

he would seeme to have Philosophie on his side;

straining her wise dictates to un-philosophicall

purposes. But when Kings come so low, as to

fawn upon Philosophie, which before they nei-

ther valu’d nor understood, tis a signe that failes

not, they are then put to their last Trump. And

Philosophie as well requites them, by not suffer-

ing her gold’n sayings either to become their lipps,

or to be us’d as masks and colours of injurious and

violent deeds. So that what they presume to bor-

row from her sage and vertuous rules, like the

Riddle of Sphinx not understood, breaks the neck

of thir own cause.

But now againe to Politics: He cannot think the

Majestie of the Crowne of England to be bound by any

Coronation Oath in a blind and brutish formalitie, to

consent to whatever its Subjects in Parlament shall

require. What Tyrant could presume to say more,

when he meant to kick down all Law, Goverment,

and bond of Oath? But why he so desires to ab-

solve himself the Oath of his Coronation would

be worth the knowing. It cannot but be yeelded,

that the Oath which bindes him to performance of

his trust, ought in reason to contain the summ of

what his chief trust and Office is. But if it nei-

ther doe enjoyn, nor mention to him, as a part of

his duty, the making or the marring of any Law

or scrap of Law, but requires onely his assent to

those Laws which the People have already chos’n,

or shall choose (for so both the Latin of that Oath,

and the old English, and all Reason admits, that

the People should not lose under a new King what

freedom they had before) then that Negative

voice so contended for, to deny the passing of any

Law which the Commons choose, is both against

the Oath of his Coronation, and his Kingly Office.

And if the King may deny to pass what the Par-

lament hath chos’n to be a Law, then doth the

King make himself Superiour to his whole King-

dom; which not onely the general Maxims of

Policy gainsay, but eev’n our own standing Laws,

as hath bin cited to him in Remonstrances heerto-

fore, that The King hath two Superiours, the Law, and his

Court of Parlament. But this he counts to be a blind

and brutish formality, whether it be Law, or Oath,

or his duty, and thinks to turn it off with whole-

som words and phrases, which he then first learnt

of the honest People, when they were so oft’n com-

pell’d to use them against those more truely blind

and brutish formalities thrust upon us by his own

command.

As for his instance in case Hee and the House of

Peers attempted to enjoyne the House of Commons, it

beares no equalitie; for hee and the Peers repre-

sent but themselves, the Commons are the whole

Kingdom.

Thus he concludes his Oath to be fully discharg`d

in Governing by Laws already made, as being not

bound to pass any new, if his Reason bids him deny.

And so may infinite mischeifs grow, and a whole

Nation be ruin’d, while our general good and

safety shall depend upon the privat and overween-

ing Reason of one obstinat Man, who against all

the Kingdom, if he list, will interpret both the Law

and his Oath of Coronation by the tenor of his

own will. Which hee himself confesses to be an

arbitrary power, yet doubts not in his Argument

to imply, as if he thought it more fitt the Parla-

ment should be subject to his will, then he to their

advice, a man neither by nature nor by nurture

wise. How is it possible that hee in whom such

Principles as these were so deep rooted, could ever,

though restor’d again, have raign’d otherwise

then Tyrannically.

He objects That force was but a slavish method to

dispell his error. But how oft’n shall it be answer’d

him that no force was us’d to dispell the error out

of his head, but to drive it from off our necks: for

his error was imperious, and would command all

other men to renounce their own reason and un-

derstanding, till they perish’d under the injunction

of his all-ruling error.

He alleges the uprightness of his intentions to

excuse his possible failings; a position fals both in

Law and Divinity: Yea contrary to his own bet-

ter principles, who affirmes in the twelfth Chapter,

that The goodness of a mans intention, will not excuse

the scandall, and contagion of his example. His not

knowing, through the corruption of flattery and

Court Principles, what he ought to have known,

will not excuse his not doing what he ought to

have don: no more then the small skill of him who

undertakes to bee a Pilot, will excuse him to be

misledd by any wandring Starr mistak’n for the

Pole. But let his intentions be never so upright,

what is that to us? What answer for the reason

and the National Rights which God hath giv’n us,

if having Parlaments, and Laws and the power of

making more to avoid mischeif, wee suffer one

mans blind intentions to lead us all with our eyes

op’n to manifest destruction.

And if Arguments prevaile not with such a one,

force is well us’d; not to carry on the weakness of

our Counsels, or to convince his error, as he surmises,

but to acquitt and rescue our own reason, our own

consciences from the force and prohibition laid by

his usurping error upon our Liberties and under-

standings.

Never thing pleas`d him more then when his judge-

ment concur’d with theirs. That was to the ap-

plause of his own judgement, and would as well

have pleas’d any self-conceited man.

Yea in many things he chose rather to deny himselfe

then them. That is to say in trifles. For of his own

Interests and Personal Rights he conceavs himself

Maister. To part with, if he please, not to contest

for, against the Kingdom which is greater then he,

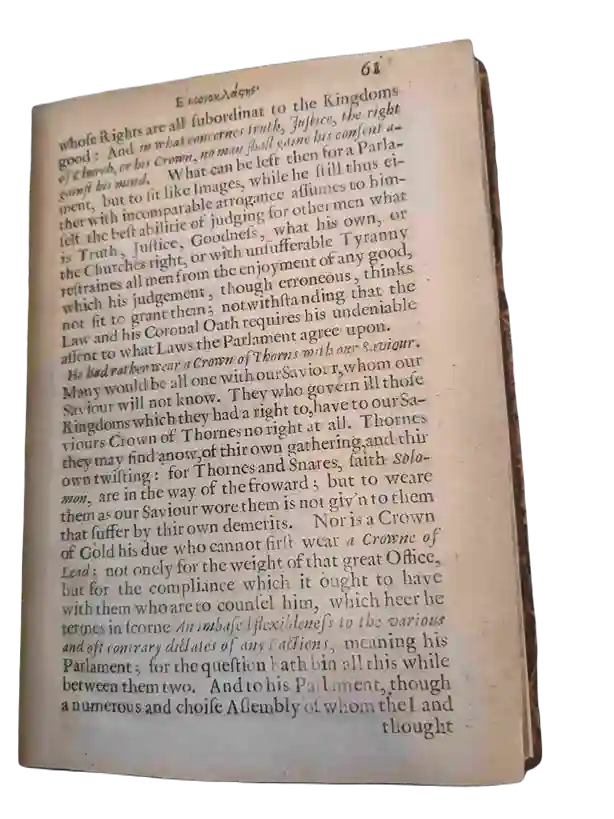

whose Rights are all subordinat to the Kingdoms

good: And in what concernes truth, Justice, the right

of Church, or his Crown, no man shall gaine his consent a-

gainst his mind. What can be left then for a Parla-

ment, but to sit like Images, while he still thus ei-

ther with incomparable arrogance assumes to him-

self the best abilitie of judging for other men what

is Truth, Justice, Goodness, what his own, or

the Churches Right, or with unsufferable Tyranny

restraines all men from the enjoyment of any good,

which his judgement, though erroneous, thinks

not fit to grant them; notwithstanding that the

Law and his Coronal Oath requires his undeniable

assent to what Laws the Parlament agree upon.

He had rather wear a Crown of Thorns with our Saviour.

Many would be all one with our Saviour, whom our

Saviour will not know. They who govern ill those

Kingdoms which they had a right to, have to our Sa-

viours Crown of Thornes no right at all. Thornes

they may find anow, of thir own gathering, and thir

own twisting: for Thornes and Snares, saith Solo-

mon, are in the way of the froward; but to weare

them as our Saviour wore them is not giv’n to them

that suffer by thir own demerits. Nor is a Crown

of Gold his due who cannot first wear a Crowne of

Lead; not onely for the weight of that great Office,

but for the compliance which it ought to have

with them who are to counsel him, which heer he

termes in scorne An imbased flexibleness to the various

and oft contrary dictates of any Factions, meaning his

Parlament; for the question hath bin all this while

between them two. And to his Parlament, though

a numerous and choise Assembly of whom the Land

thought wisest, he imputes rather then to himself,

want of reason, neglect of the Public, interest of parties,

and particularitie of private will and passion ; but with

what modesty or likelihood of truth it will be wea-

risom to repeat so oft’n.

He concludes with a sentence faire in seeming,

but fallacious. For if the conscience be ill edifi’d,

the resolution may more befitt a foolish then a Chri-

stian King, to preferr a self-will’d conscience before

a Kingdoms good; especially in the deniall of

that which Law and his Regal Office by Oath bids

him grant to his Parlament, and whole Kingdom

righfully demanding. For wee may observe him

throughout the discours to assert his Negative

power against the whole Kingdom; now under the

specious Plea of his conscience and his reason, but

heertofore in a lowder note, Without us, or against our

consent, the Votes of either or of both Houses together,

must not, cannot, shall not: Declar. May 4. 1642.

With these and the like deceavable Doctrines he

levens also his Prayer.

XXVIII. Intitl`d Meditations

upon Death.

IT might be well thought by him who Reads

no furder then the Title of this last Essay,

that it requir’d no Answer. For all other

human things are disputed, and will be vari-

ously thought of to the Worlds end. But

this business of Death is a plaine case, and admitts

no controversie: In that center all Opinions meet.

Nevertheless, since out of those few mortifying

howers that should have bin intirest to themselves,

and most at peace from all passion, and disquiet,

he can afford spare time to inveigh bitterly against

that Justice which was don upou him; it will be

needfull to say somthing in defence of those pro-

ceedings; though breifly, in regard so much on

this Subject hath been Writt’n lately.

It happn’d once, as we find in Esdras and Josephus,

Authors not less beleiv’d then any under sacred,

to be a great and solemn debate in the Court of

Darius, what thing was to be counted strongest of

all other. He that could resolve this, in reward of

his excelling wisdom, should be clad in Purple,

drink in Gold, sleep on a Bed of Gold, and sitt next

to Darius. None but they doubtless who were re-

puted wise, had the Question propounded to them.

Who after som respit giv’n them by the King to

consider, in ful Assembly of all his Lords and gravest

Counsellors, returnd severally what they thought.

The first held that Wine was strongest; another

that the King was strongest. But Zorobabel Prince

of the Captive Jewes, and Heire to the Crown of

Judah, beeing one of them, proov’d Women to be

stronger then the King, for that he himself had seen

a Concubin take his Crown from off his head to set

it upon her own: And others besides him have

lately seen the like Feat don, and not in jest. Yet

he proov’d on, and it was so yeilded by the King

himself, and all his sages, that neither Wine nor

Women, nor the King, but Truth, of all other

things was the strongest. For me, though neither

ask’d, nor in a Nation that gives such rewards to

wisdom, I shall pronounce my sentence somwhat

different from Zorobabel; and shall defend, that ei-

ther Truth and Justice are all one, for Truth is but

Justice in our knowledge, and Justice is but Truth

in our practice, and he indeed so explaines him-

self in saying that with Truth is no accepting of

Persons, which is the property of Justice; or els,

if there be any odds, that Justice, though not

stronger then Truth, yet by her office is to put

forth and exhibit more strength in the affaires of

mankind. For Truth is properly no more then

Contemplation; and her utmost efficiency is but

teaching: but Justice in her very essence is all

strength and activity; and hath a Sword put into

her hand, to use against all violence and oppression

on the earth. Shee it is most truly, who accepts

no Person, and exempts none from the severity

of her stroke. Shee never suffers injury to pre-

vaile, but when falshood first prevailes over Truth;

and that also is a kind of Justice don on them who

are so deluded. Though wicked Kings and Ty-

rants counterfet her Sword, as som did that Buck-

ler, fabl’d to fall from Heav’n into the Capitol, yet

shee communicates her power to none but such as

like her self are just, or at least will doe Justice.

For it were extreme partialitie and injustice, the

flat denyall and overthrow of her self, to put her

own authentic Sword into the hand of an unjust

and wicked Man, or so farr to accept and exalt one

mortal Person above his equals, that he alone shall

have the punishing of all other men transgressing,

and not receive like punishment from men, when

he himself shall be found the highest transgressor.

We may conclude therfore that Justice, above

all other things, is and ought to be the strongest:

Shee is the strength, the Kingdom, the power and

majestie of all Ages. Truth her selfe would sub-

scribe to this, though Darius and all the Monarchs

of the World should deny. And if by sentence

thus writt’n it were my happiness to set free the

minds of English men from longing to return poor-

ly under that Captivity of Kings, from which the

strength and supreme Sword of Justice hath deli-

ver’d them, I shall have don a work not much in-

ferior to that of Zorobabel: who by well praising

and extolling the force of Truth, in that contem-

plative strength conquer’d Darius; and freed his

Countrey, and the people of God from the Cap-

tivity of Babylon. Which I shall yet not despaire

to doe, if they in this Land whose minds are yet

Captive, be but as ingenuous to acknowledge the

strength and supremacie of Justice, as that Heathen

King was, to confess the strength of Truth: or let

them but as he did, grant that, and they will soon

perceave that Truth resignes all her outward

strength to Justice: Justice therfore must needs be

strongest, both in her own and in the strength of

Truth. But if a King may doe among men what-

soever is his will and pleasure, and notwithstand-

ing be unaccountable to men, then contrary to this

magnifi’d wisdom of Zorobabel, neither Truth nor

Justice, but the King is strongest of all other

things: which that Persian Monarch himself in

the midst of all his pride and glory durst not as-

sume.

Let us see therfore what this King hath to affirm,

why the sentence of Justice and the weight of that

Sword which shee delivers into the hands of men,

should be more partial to him offending, then to

all others of human race. First, he pleads that No

Law of God or man gives to subjects any power of ju-

dicature without or against him. Which assertion

shall be prov’d in every part to be most untrue.

The first express Law of God giv’n to mankind,

was that to Noah, as a Law in generall to all the

sons of men. And by that most ancient and uni-

versal Law, Whosoever sheddeth mans blood, by man

shall his blood be shed; we finde heer no exception.

If a King therefore doe this, to a King, and that by

men also, the same shall be don. This in the Law

of Moses, which came next, several times is repea-

ted, and in one place remarkably, Numb. 35. Ye

shall take no satisfaction for the life of a murderer, but

he shall surely be put to death: the Land cannot be clean-

sed of the blood that is shedd therein, but by the blood

of him that shedd it. This is so spok’n, as that

which concern’d all Israel, not one man alone to

see perform’d; and if no satisfaction were to be ta-

k’n, then certainly no exceptiou. Nay the King,

when they should set up any, was to observe the

whole Law, and not onely to see it don, but to doe

it; that his heart might not be lifted up above his Bre-

thren, to dreame of vain and reasonless prerogatives

or exemptions, wherby the Law it self must needs

befounded in unrighteousness.

And were that true, which is most fals, that all

Kings are rhe Lords Anointed, it were yet absurd

to think that the Anointment of God, should be as

it were a charme against Law; and give them pri-

vilege who punish others, to sin themselves unpu-

nishably. The high Preist was the Lords anointed

as well as any King, and with the same consecrated

oile: yet Salomon had put to death Abiather, had it

not bin for other respects then that anointment.

If God himself say to Kings, Touch not mine anointed,

meaning his chos’n people, as is evident in that

Psalme, yet no man will argue thence, that he pro-

tects them from Civil Lawes if they offend, then

certainly, though David as a privat man, and in

his own cause, feard to lift his hand against the

Lords Anointed, much less can this forbidd the

Law, or disarm justice from having legall power

against any King. No other supreme Maigstrate

in what kind of Goverment soever laies claim to

any such enormous Privilege; wherfore then

should any King who is but one kind of Magistrat,

and set over the People for no other end then

they?

Next in order of time to the Laws of Moses, are

those of Christ, who declares professedly his judi-

cature to be spiritual, abstract from civil manage-

ments, and therfore leaves all Nations to thir own

particular Lawes, and way of Goverment. Yet

because the Church hath a kind of Jurisdiction

within her own bounds, and that also, though in

process of time much corrupted and plainly turn’d

into a corporal judicature, yet much approov’d by

this King, it will be firm anough and valid against

him, if subjects, by the Laws of Church also, be

invested with a power of judicature both without and

against thir King, though pretending, and by them

acknowledg’d next and immediatly under Christ su-

preme head and Governour. Theodosius the Emperour

having made a slaughter of the Thessalonians for se-

dition, but too cruelly, was excommunicated to

his face by Saint Ambrose, who was his subject:

and excommunion is the utmost of Ecclesiastical

Judicature, a spiritual putting to death. But this,

yee will say, was onely an example. Reade then

the Story; and it will appeare, both that Ambrose

avouch’d it for the Law of God, and Theodosius

confest it of his own accord to be so; and that the

Law of God was not to be made voyd in him, for any

reverence to his Imperial power. From hence, not

to be tedious, I shall pass into our own Land of

Brittain; and show that Subjects heer have exer-

cis’d the utmost of spiritual Judicature, and more

then spiritual against thir Kings, his Predecessours.

Vortiger for committing incest with his Daughter,

was by Saint German, at that time his subject,

curs’d and condemn’d in a Brittish Counsel about

the yeare 448; and therupon soon after was de-

pos’d. Mauricus a King in Wales, for breach of

Oath, and the murder of Cynetus was excommuni-

cated, and curst with all his offspring, by Oudoceus

Bishop of Landaff in full Synod, about the yeare

560; and not restor’d, till he had repented. Mor-

cant another King in Wales having slain Frioc his

Unkle, was faine to come in Person and receave

judgement from the same Bishop and his Clergie;

who upon his penitence acquitted him, for no o-

ther cause then lest the Kingdom should be desti-

tute of a Successour in the Royal Line. These

examples are of the Primitive, Brittish, and Epis-

copal Church; long ere they had any commerce or

communion with the Church of Rome. What

power afterward of deposing Kings, and so conse-

quently of putting them to death, was assum’d

and practis’d by the Canon Law, I omitt as a thing

generally known. Certainly if whole Councels

of the Romish Church have in the midst of their

dimness discernd so much of Truth, as to Decree

at Constance, and at Basil, and many of them to a-

vouch at Trent also, that a Councel is above the

Pope, and may judge him, though by them not

deni’d to be the Vicar of Christ, we in our clearer

light may be asham’d not to discern furder, that a

Parlament is, by all equity, and right, above a King,

and may judge him, whose reasons and pretensions

to hold of God onely, as his immediat Vicege-

rent, we know how farr fetch’d they are, and in-

sufficient.

As for the Laws of man, it would ask a Volume

to repeat all that might be cited in this point a-

gainst him from all Antiquity. In Greece, Orestes the

Son of Agamemnon, and by succession King of Ar-

gos, was in that Countrey judg’d and condemn’d

to death for killing his Mother: whence escaping,

he was judg’d againe, though a Stranger, before the

great Counsel of Areopagus in Athens. And this me-

morable act of Judicature, was the first that brought

the Justice of that grave Senat into fame and high

estimation over all Greece for many ages after.

And in the same Citty Tyrants were to undergoe

Legall sentence by the Laws of Solon. The Kings

of Sparta, though descended lineally from Hercu-

les esteem’d a God among them, were oft’n judg’d

and somtimes put to death by the most just and re-

nowned Laws of Lycurgus; who, though a King,

thought it most unequal to bind his Subjects by a-

ny Law, to which he bound not himself. In Rome

the Laws made by Valerius Publicola, and what the

Senate decreed against Nero, that hee should be

judg’d and punish’d according to the Laws of thir

Ancestors, and what in like manner was decreed a-

gainst other Emperours, is vulgarly known. And

that the Civil Law warrants like power of Judica-

ture to Subjects against Tyrants, is writt’n clearly

by the best and famousest Civilians. For if it was

decreed by Theodosius, and stands yet firme in the

Code of Justinian, that the Law is above the Em-

perour, then certainly the Emperour being under

Law, the Law may judge him, and if judge him,

may punish him proving tyrannous: how els is

the Law above him, or to what purpose. These

are necessary deductions; and therafter hath bin

don in all Ages and Kingdoms, oftner then to be

heer recited.

But what need we any furder search after the

Law of other Lands, for that which is so fully

and so plainly set down lawfull in our owne.

Where ancient Books tell us, Bracton, Fleta, and

others, that the King is under Law, and inferiour

to his Court of Parlament; that although his

place to doe Justice be highest, yet that he stands as

liable to receave Justice, as the meanest of his King-

dom. Nay, Alfred the most worthy King, and by

som accounted first absolute Monarch of the Sax-

ons heer, so ordain’d; as is cited out of an ancient

Law Book call’d the Mirror, in Rights of the King-

dom, p. 31. where it is complain’d on, As the sovran

abuse of all, that the King should be deem`d above the

Law, whereas he ought to be subject to it by his Oath: Of

which Oath anciently it was the last clause, that

the King should be as liable, and obedient to suffer right,

as others of his people. And indeed it were but fond

and sensless, that the King should be accountable

to every petty suit in lesser Courts, as we all know

he was, and not be subject to the Judicature of Par-

lament in the main matters of our common safety

or destruction; that hee should be answerable in

the ordinary cours of Law for any wrong don to a

privat Person, and not answerable in Court of Par-

lament for destroying the whole Kingdom. By all

this, and much more that might be added as in an

argument overcopious rather then barren, we see

it manifest that all Laws both of God and Man are

made without exemption of any person whomsoe-

ver; and that if Kings presume to overtopp the

Law by which they raigne for the public good,

they are by Law to be reduc’d into order: and that

can no way be more justly, then by those who ex-

alted them to that high place. For who should

better understand thir own Laws, and when they

are transgrest, then they who are govern’d by them,

and whose consent first made them: and who can

have more right to take knowledge of things don

within a free Nation then they within themselves?

Those objected Oaths of Allegeance and Supre-

macy we swore, not to his Person, but as it was in-

vested with his Autority; and his autority was

by the People first giv’n him conditionally, in Law

and under Law and under Oath also for the King-

doms good, and not otherwise: the Oathes then

were interchang’d, and mutual; stood and fell to-

gether; he swore fidelity to his trust; not as a de-

luding ceremony, but as a real condition of their

admitting him for King; and the Conqueror

himself swore it ofter then at his Crowning: they

swore Homage, and Fealty to his Person in that

trust. There was no reason why the Kingdom

should be furder bound by Oaths to him, then hee

by his Coronation Oath to us, which he hath every

way brok’n: and having brok’n, the ancient Crown-

Oath of Alfred above mention’d, conceales not

his penalty.

As for the Covnant, if that be meant, certainly

no discreet Person can imagin it should bind us to

him in any stricter sense then those Oaths formerly.

The acts of Hostility which we receiv’d from him,

were no such dear obligements that we should ow

him more fealty and defence for being our Enemy,

then we could before when we took him onely for

a King. They were accus’d by him and his Party

to pretend Liberty and Reformation, but to have

no other end then to make themselves great, and to

destroy the Kings Person and Autority. For which

reason they added that third Article, testifying to

the World, that as they were resolv’d to endeavor

first a Reformation in the Church, to extirpate

Prelacy, to preserve the Rights of Parlament, and

the Liberties of the Kingdom, so they intended, so

farr as it might consist with the preservation and

defence of these, to preserve the Kings Person and

Autority; but not otherwise. As farr as this comes

to, they Covnant and Swear in the sixth Article to

preserve and defend the persons and autority of one

another, and all those that enter into that League;

so that this Covnant gives no unlimitable exempti-

on to the Kings Person, but gives to all as much de-

fence and preservation as to him, and to him as much

as to thir own Persons, and no more; that is to say, in

order and subordination to those maine ends for

which we live and are a Nation of men joynd in so-

ciety either Christian or at least human. But if the

Covnant were made absolute, to preserve and de-

fend any one whomsoever, without respect had,

either to the true Religion, or those other Supe-

riour things to be defended and preserv’d however,

it cannot then be doubted, but that the Covnant

was rather a most foolish, hasty, and unlawfull Vow,

then a deliberate and well-waighd Covnant; swear-

ing us into labyrinths, and repugnances, no way to

be solv’d or reconcil’d, and therfore no way to be

kept: as first offending against the Law of God, to

Vow the absolute preservation, defence, and main-

taining of one Man though in his sins and offences

never so great and hainous against God or his

Neighbour; and to except a Person from Justice,

wheras his Law excepts none. Secondly, it offends

against the Law of this Nation, wherein, as hath

bin prov’d, Kings in receiving Justice, and under-

going due tryall, are not differenc’d from the mea-

nest Subject. Lastly, it contradicts and offends a-

gainst the Covnant itself, which vows in the fourth

Article to bring to op’n triall and condigne punish-

ment all those that shall be found guilty of such

crimes and Delinquencies, wherof the King by his

own Letters and other undenyable testimonies not

brought to light till afterward, was found and

convicted to be the cheif actor in what they thought

him at the time of taking that Covnant, to be o-

verrul’d only by evil Counselers; and those, or

whomsoever they should discover to be principall,

they vow’d to try, either by thir own supreme Judi-

catories, for so eev’n then they call’d them, or by o-

thers having power from them to that effect. So that

to have brought the King to condign punishment

hath not broke the Covnant, but it would have

broke the Covnant to have sav’d him from those

Judicatories, which both Nations declar’d in that

Covnant to be Supreme against any person whatsoe-

ver. And if the Covnant swore otherwise to preserve

him then in the preservation of true Religion and

our Liberties, against which he fought, if not in

Armes, yet in Resolution to his dying day, and

now after death still fights against, in this his Book,

the Covnant was better brok’n, then he sav’d. And

God hath testifi’d by all propitious and evident

signes, whereby in these latter times he is wont to

testifie what pleases him; that such a solemn, and

for many Ages unexampl’d act of due punishment,

was no mockery of Justice, but a most gratefull and

well-pleasing Sacrifice. Neither was it to cover thir

perjury as he accuses, but to uncover his perjury to

the Oath of his Coronation.

The rest of his discours quite forgets the Title;

and turns his Meditations upon death into oblo-

quie and bitter vehemence against his Judges and

Accusers; imitating therin, not our Saviour, but

his Grand-mother Mary Queen of Scots, as also in

the most of his other scruples, exceptions, and e-

vasions: and from whom he seems to have learnt,

as it were by heart, or els by kind, that which is

thought by his admirers to be the most vertuous,

most manly, most Christian, and most Martyr-like

both of his words and speeches heer, and of his an-

swers and behaviour at his Tryall.

It is a sad fate, he saith, to have his Enemies both

Accusers, Parties, and Judges. Sad indeed, but no

sufficient Plea to acquitt him from being so judg’d.

For what Malefactor might not somtimes plead the

like? If his own crimes have made all men his E-

nemies, who els can judge him? They of the Pow-

der-plot against his Father might as well have plea-

ded the same. Nay at the Resurrection it may as

well be pleaded, that the Saints who then shall

judge the World, are both Enemies, Judges, Parties,

and Accusers.

So much he thinks to abound in his own defence,

that he undertakes an unmeasurable task; to be-

speak the singular care and protection of God over all

Kings, as being the greatest Patrons of Law, Justice,

Order, and Religion on Earth. But what Patrons

they be, God in the Scripture oft anough hath ex-

prest; and the earth it self hath too long groan’d

under the burd’n of thir injustice, disorder, and

irreligion. Therfore To bind thir Kings in chaines,

and thir Nobles with links of Iron, is an honour be-

longing to his Saints; not to build Babel, which

was Nimrods work, the first King, and the beginning

of his Kingdom was Babel, but to destroy it, especi-

ally that spiritual Babel: and first to overcome those

European Kings, which receive thir power; not

from God, but from the beast; and are counted no

better then his ten hornes. These shall hate the great

Whore, and yet shall give thir Kingdoms to the Beast

that carries her; they shall committ Fornication with

her, and yet shall burn her with fire, and yet shall la-

ment the fall of Babylon, where they fornicated with

her.

Thus shall they be too and fro, doubtfull and

ambiguous in all thir doings, untill at last, joyning

thir Armies with the Beast, whose power first rais’d

them, they shall perish with him by the King of

Kings against whom they have rebell’d; and the

Foules shall eat thir flesh. This is thir doom writt’n,

and the utmost that wee find concerning them in

these latter days; which we have much more cause

to beleeve, then his unwarranted Revelation heer,

prophecying what shall follow after his death, with

the spirit of Enmity, not of Saint John.

He would fain bring us out of conceit with the

good success which God hath voutsaf’d us. Wee

measure not our Cause by our success, but our suc-

cess by our Cause. Yet certainly in a good Cause

success is a good confirmation; for God hath pro-

mis’d it to good men almost in every leafe of Scrip-

ture. If it argue not for us, we are sure it argues

not against us; but as much or more for us, then

ill success argues for them; for to the wicked, God

hath denounc’d ill success in all they take in

hand.

He hopes much of those softer tempers, as he calls

them, and less advantag`d by his ruin, that thir con-

sciences doe already gripe them. Tis true, there be

a sort of moodie, hot-brain’d, and alwayes unedi-

fy’d consciences; apt to engage thir Leaders into

great and dangerous affaires past retirement, and

then, upon a sudden qualm and swimming of thir

conscience, to betray them basely in the midst of

what was cheifly undertak’n for their sakes. Let

such men never meet with any faithfull Par-

lament to hazzard for them; never with any noble

Spirit to conduct and lead them out, but let them

live and die in servile condition and thir scrupu-

lous queasiness, if no instruction will confirme

them. Others there be in whose consciences the

loss of gaine, and those advantages they hop’d for,

hath sprung a sudden leake. These are they that

cry out the Covnant brok’n, and to keep it better

slide back into neutrality, or joyn actually with

Incendiaries and Malignants. But God hath emi-

nently begun to punish those, first in Scotland, then

in Ulster, who have provok’d him with the most

hatefull kind of mockerie, to break his Covnant

under pretence of strictest keeping it; and hath

subjected them to those Malignants, with whom

they scrupl’d not to be associats. In God there-

fore we shall not feare what their fals fraternity

can doe against us.

Hee seeks againe with cunning words to turn

our success into our sin. But might call to mind,

that the Scripture speakes of those also, who when

God slew them, then sought him; yet did but flatter

him with thir mouth, and ly’d to him with thir tongues;

for thir heart was not right with him. And there was

one, who in the time of his affliction trespass’d more

against God; This was that King Ahaz.

Hee glories much in the forgivness of his Ene-

mies; so did his Grandmother at her death.

Wise men would sooner have beleev’d him had he

not so oft’n told us so. But he hopes to erect the Tro-

phies of his charity over us. And Trophies of Cha-

rity no doubt will be as glorious as Trumpets be-

fore the almes of Hypocrites; and more especially

the Trophies of such an aspiring charitie as offers

in his Prayer to share Victory with Gods compas-

sion, which is over all his Works. Such Prayers

as these may perhaps catch the people, as was

intended: but how they please God, is to be

much doubted, though pray’d in secret, much

less writt’n to be divulg’d. Which perhaps may

gaine him after death a short, contemptible, and

soon fading reward; not what hee aimes at, to

stirr the constancie and solid firmness of any wise

Man, or to unsettle the conscience of any know-

ing Christian, if he could ever aime at a thing so

hopeless, and above the genius of his Cleric elo-

cution, but to catch the worthles approbation of

an inconstant, irrational, and Image-doting rab-

ble. The rest, whom perhaps ignorance without

malice, or som error, less then fatal, hath for the

time misledd, on this side Sorcery or obduration,

may find the grace and good guidance to bethink

themselves, and recover.

THE END.