Somerset v. Steuart (1772)

Introduction

James Somerset was the enslaved personal manservant of Charles Steuart, a Scottish-born Virginia merchant who became the chief customs officer charged with enforcing the unpopular Stamp Act and Townshend Duties in the northern American colonies. Somerset had been brought to Virginia as a child and lived there with Steuart for 20 years, before traveling with him to most of the port cities along the northern seaboard from 1766-69. In Philadelphia, Boston and New York, the pair encountered political unrest and nascent antislavery activism. Steuart relocated to London in late 1769, taking Somerset with him. Two years later, in October 1771, Somerset tried to secure his freedom. Instead, Steuart had him captured and imprisoned on the ship Ann and Mary bound for Jamaica, where he was to be sold into plantation labor. Somerset’s godparents – he had converted to Christianity during his time in England – sued for a writ of habeas corpus, alleging that he was held against his will and should be freed.1 Mark S. Weiner. “Notes and Documents: New Biographical Evidence on Somerset’s Case.” Slavery & Abolition 23, no. 1 (2002): 121-136.

Somerset and his supporters enlisted the aid of the prominent English abolitionist Granville Sharp with the aim of turning the case into a test of the legal justification for slavery. Somerset’s advocates argued that while colonial laws might establish legal grounding for slavery, neither Parliamentary statute nor English common law had ever positively recognized slavery, and therefore it was not legal in the metropole. Pro-slavery interests, similarly, saw this as an important test case; the Society of West India Planters and Merchants bankrolled Steuart’s legal fees.2Andrew Lyall, ed. Granville Sharp’s Cases on Slavery. (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2017) Legal advocates for Somerset’s enslaver, Charles Steuart, contended that freeing Somerset would set a dangerous precedent for the abrogation of property rights and could potentially free 14,000 to 15,000 enslaved people in England.

Lord Chief Justice Mansfield found in Somerset’s favor, declaring his freedom. He purposefully construed his decision narrowly, finding that an enslaver could not remove an enslaved person from England against the enslaved person’s will and that an enslaved person could sue for habeas corpus in such a scenario. He avoided ruling on the broader question of slavery’s legal status in England or in the colonies. Nonetheless, Mansfield’s commentary in delivering the decision did carry the suggestion that positive law, rather than custom, was necessary to establish the legality of slavery.3William M. Wiecek, “Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American world.” University of Chicago Law Review 42, no. 1 (1974): 86–146; William R. Cotter, “The Somerset Case and the Abolition of Slavery in England.” History, 79, no. 255 (Feb. 1994): 31–56.

There is substantial debate among scholars about the most authoritative version of the Somerset case report. The verdict was read orally, and there was not a standard form of court reporting in this period. Many of Mansfield’s papers were destroyed in the 1780 Gordon House riots, and so his notes about this case are not extant. The version presented here is based on notes taken by Capel Lofft, a junior barrister who witnessed the trial. However, there are also other reports which contain notable variations. These include William Isaac Blanchard’s stenographic report produced for Granville Sharp and running reports printed by contemporary newspapers over several editions.4David Worrall, “How Much Do We Really Know About Somerset v. Stewart (1772)? The Missing Evidence of Contemporary Newspapers.” Slavery & Abolition 43, no. 3 (2022): 574-593

The case drew attention across Britain’s empire as it was argued. As the several advertisements for fugitive enslaved people, printed in Williamsburg, Virginia’s Virginia Gazette demonstrate, the notion that the Somerset verdict established England as free soil was widespread and motivated some enslaved people to seek to escape there. Likewise, newspaper accounts from London itself describe people of African descent gathering near Charing Cross to monitor the trial and organize for “the more effective recovery of their freedom.” In the decades following Somerset, habeas corpus became a crucial tool in antislavery litigation.

– Michael Becker and Kirsten Sword

Virginia Gazette excerpts

As you read the case, consider the following questions:

- What “facts” does the case reporting include about James Somerset, Charles Steuart, and other interested parties? Do you notice any omitted details or errors? How might these matter to those interpreting the significance of the case?

- How and why do lawyers for each side draw on precedent around villenage (a form of serfdom common in medieval England) and slavery in other European empires in developing their arguments?

- What are the implications in each argument for the relationship between laws passed by Parliament for the whole empire, and laws passed either in England or in specific colonies?

- What does the tone and style of arguments (e.g. jokes about enslavers eating enslaved people) tell us about the atmosphere in the courtroom?

- How do the participants in the case explain habeas corpus? How do these arguments compare with other appeals to habeas corpus in the documents on this site or elsewhere? How effective are appeals to habeas corpus as an antislavery strategy?

- Why do you think Mansfield constructed his decision as narrowly as he did?

- How does the tone and content of Capel Lofft’s report compare and contrast with the newspaper coverage of this case?

Further Reading

- David Waldstreicher and Matthew Mason, eds. Somerset v. Steuart and America. (Omohundro Institute for History and Culture Press. Forthcoming 2025.)

- William R. Cotter, “The Somerset Case and the Abolition of Slavery in England.” History, 79, no. 255 (Feb. 1994): 31–56.

- Daniel J. Hulsebosch, “Nothing But Liberty: Somerset’s Case and the British Empire.” Law and History Review 24, 3 (2006): 647–58

- Andrew Lyall, ed. Granville Sharp’s Cases on Slavery. (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2017)

- William M. Wiecek, “Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American world.” University of Chicago Law Review 42, no. 1 (1974): 86–146

- Steven M. Wise. Though the Heavens May Fall: The Landmark Trial That Led to the End of Human Slavery. (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2006).

- David Worrall, “How Much Do We Really Know About Somerset v. Stewart (1772)? The Missing Evidence of Contemporary Newspapers.” Slavery & Abolition 43, no. 3 (2022): 574-593

Sources

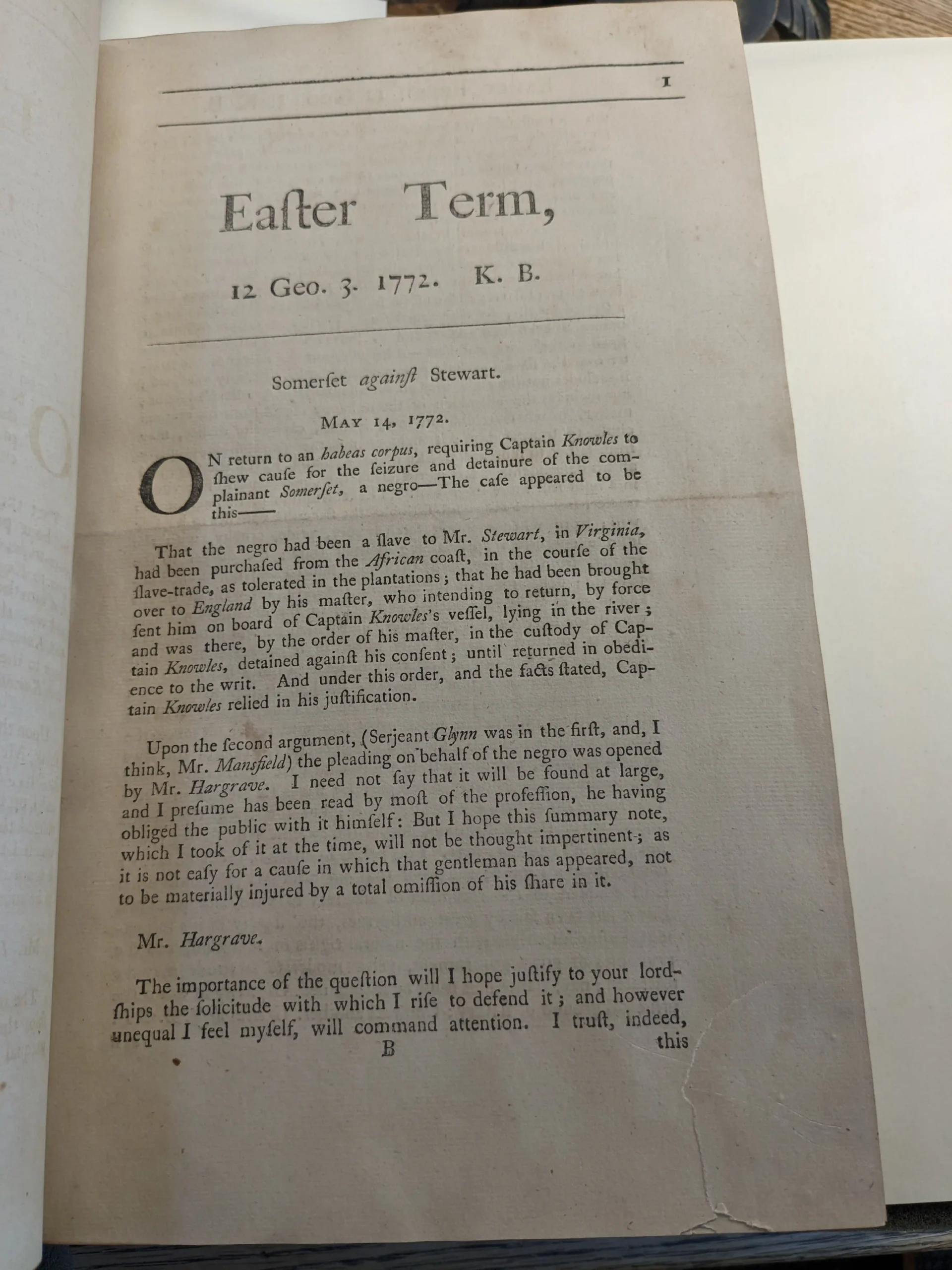

- Capel Lofft.”Somerset v. Stewart” in Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Court of King`s Bench From Easter Term 12 Geo. 3. to Michaelmas 14 Geo. 3. (both inclusive) with some select CasesIn the Court of Chancery, and of the Common Pleas… (London: William Owen, 1776), pgs. 1-19.

- Cornell University Law Library Special Collections.

- Transcription by Michael Becker and Kirsten Sword.

- Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Virginia), May 7, 1772, September 30, 1773, and June 30, 1774 issues. America’s Historical Newspapers and Periodicals.

- Transcription by Michael Becker.

Cite this page

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

REPORTS

OF

CASES

ADJUDGED IN THE

Court of King`s Bench

From Easter Term 12 Geo. 3. to Michaelmas

14 Geo. 3. (both inclusive)

With some select Cases

In the Court of Chancery,

AND

Of the Common Pleas,

WHICH ARE WITHIN THE SAME PERIOD.

TO WHICH IS ADDED,

THE CASE OF GENERAL WARRANTS,

AND

A COLLECTION OF MAXIMS.

By CAPEL LOFFT, ESQUIRE, of LINCOLN’S INN.

LONDON:

Printed by W. STRAHAN and M. WOODFALL, Law Printers to

His Majesty.

And published by WILLIAM OWEN, in Fleet-Street.

MDCCLXXVI.

[1]

Easter Term,

12 Geo. 3. 1772. K. B.

Somerset against Stewart.

.

ON return to an habeas corpus, requiring Captain Knowles to

shew cause for the seizure and detainure of the com-

plainant Somerset, a negro – The case appeared to be

this –

That the negro had been a slave to Mr. Stewart, in Virginia,

had been purchased from the African coast, in the course of the

slave-trade, as tolerated in the plantations; that he had been brought

over to England by his master, who intending to return, by force

sent him on board of Captain Knowles‘s vessel, lying in the river;

and was there, by the order of his master, in the custody of Cap-

tain Knowles, detained against his consent; until returned in obedi-

ence to the writ. And under this order, and the facts stated, Cap-

tain Knowles relied in his justification.

Upon the second argument, (Serjeant Glynn was in the first, and, I

think, Mr. Mansfield) the pleading on behalf of the negro was opened

by Mr. Hargrave. I need not say that it will be found at large,

and I presume has been read by most of the profession, he having

obliged the public with it himself: But I hope this summary note,

which I took of it at the time, will not be thought imperitent; as

it is not easy for a cause in which that gentleman has appeared, not

to be materially injured by a total omission of his share in it.

Mr. Hargrave.

The importance of the question will I hope justify to your lord-

ships the solicitude with which I rise to defend it; and however

unequal I feel myself, will command attention. I trust, indeed,

[3]

and Pufendorf, b. 6. c. 3. § 5. approves the making slaves of captives

in war. The author of the Spirit of the Laws denies, except for self-

preservation, and then only a temporary slaver. Dr. Rutherforth, in

his Principles of Natural Law, and Locke, absolutely against it. As

to contract; want of sufficient consideration justly gives full exception

to the considering of it as contract. If it cannot be supported

against parents, certainly not against children. Slavery imposed for

the performance of public works for civil crimes, is much more de-

fensible, and rests on quite different foundations. Domestic slavery,

the object of the present consideration, is now submitted to observa-

tion in the ensuing account, its first commencement, progress, and

gradual decrease: It took origin very early among the barbarous na-

tions, continued in the state of the Jews, Greeks, Romans, and Ger-

mans; was propagated by the last over the numerous and extensive

countries they subdued. Incompatible with the mild and humane

precepts of christianity, it began to be abolished in Spain, as the inha-

bitants grew enlightened and civilized, in the 8th century; it’s de-

cay extended over Europe in the 14th; was pretty well perfected

in the beginning of the 16th century. Soon after that period, the

discovery of America revived those tyrannic doctrines of servitude,

with their wretched consequences. There is now at last an at-

tempt, and the first yet known, to introduce it into England; long

and uninterrupted usage from the origin of the common law, stands

to oppose its revival. All kinds of domestic slavery were prohibited,

except villenage. The villain was bound indeed to perpetual ser-

vice; liable to the arbitrary disposal of his lord. There were two

sorts; villain regardant, and in gross: The former as belonging to a

manor, to the lord of which his ancestors had done villain service;

in gross, when a villain was granted over by the lord. Villains were

originally captives at the conquest, or troubles before. Villenage could

commence no where but in England, it was necessary to have pre-

scription for it. A new species has never arisen till now; for had

it, remedies and powers there would have been at law: Therefore

the most violent presumption against is the silence of the laws, were

there nothing more. ‘Tis very doubtful whether the laws of England

will permit a man to bind himself by contract to serve for life: Cer-

tainly will not suffer him to invest another man with despotism, nor

prevent his own right to dispose of property. If disallowed by consent

of parties, much more when by force; if made void when com-

menced here, much more when imported. If these are true argu-

ments, they reach the King himself as well as the subject. Dr. Ru-

therforth says, if the civil law of any nation does not allow of slavery,

prisoners of war cannot be made slaves. If the policy of our laws

admits not slavery, neither fact nor reason are for it. A man, it is

said, told the judges of the Star-Chamber, in the case of a Russian

slave whom they had ordered to be scourged and imprisoned, that

the air of England was too pure for slavery. The parliament after-

wards punished the judges of the Star-Chamber for such usage of the

[4]

Russian, on his refusing to answer interrogatories. There are very

few instances, few indeed, of decisions as to slaves, in this country.

Two in Charles the 2d. where it was adjudged trover would lie.

Chamberlayne and Perrin, Will. 3d. trover brought for taking a

negro slave, adjudged it would not lie. – 4th Ann. action of trover;

judgment by default: On arrest of judgment, resolved that trover

would not lie. Such the determinations in all but two cases; and

those the earliest, and disallowed by the subsequent decisions. Lord

Holt – As soon as a slave enters England he becomes free. Stanley

and Harvey, on a bequest to a slave; by a person whom he had served

some years by his former master’s permission, the master claims the

bequest; Lord Northington decides for the slave, and gives him

costs. 29th of George the 2d. c. 31. implies permission in Ame-

rica, unhappily thought necessary; but the same reason subsists not

here in England. The local law to be admitted when no very great

inconvenience would follow; but otherwise not. The right of the

master depends on the condition of slavery (such as it is) in Ame-

rica. If the slave be brought hither, it has nothing left to depend on

but a supposed contract of the slave to return; which yet the law

of England cannot permit. Thus has been traced the only mode of

slavery ever been established here, villenage, long expired; I hope it

has shewn, the introducing new kinds of slavery has been cau-

tiously, and, we trust, effectually guarded against by the same laws.

Your lordships will indulge me in reciting the practice of foreign

nations. ‘Tis discountenanced in France; Bartholinus de Republicâ

denies its permission by the law of France. Molinus gives a remark-

able instance of the slave of an ambassador of Spain brought into

France: He claims liberty; his claim allowed. France even miti-

gates the ancient slavery, far from creating new. France does not

suffer even her King to introduce a new species of slavery. The other

parliaments did indeed; but the parliament of Paris, considering the

edict to import slavery as an exertion of the sovereign to the breach of

the constitution, would not register that edict. Edict 1685, permits

slavery in the colonies. Edict in 1716, recites the necessity to per-

mit in France, but under various restraints, accurately enumerated in

the Institute of French Laws. 1759 Admiralty court of France;

Causes Celebrées, title Negro. A French gentleman purchased a

slave, and sent him to St Malo`s entrusted with a friend: He came

afterwards, and took him to Paris. After ten years the servant chuses

to leave France. The master not like Mr. Stewart hurries him

back by main force, but obtains a process to apprehend him, from a

court of justice. While in prison, the servant institutes a process

against his master, and is declared free. After the permission of

slaves in the colonies, the edict of 1716 was necessary, to transfer

that slavery to Paris; not without many restraints, as before re-

marked; otherwise the ancient principles would have prevailed.

The author De Jure Novissimo, tho’ the natural tendency of his book,

as appears by the title, leads the other way, concurs with diverse

[5]

great authorities, in reprobating the introduction of a new species of

servitude. In England, where freedom is the grand object of the

laws, and dispensed to the meanest individual, shall the laws

of an infant colony, Virginia, or of a barbarous nation, Africa, pre-

vail? From the submission of the negro to the laws of England,

he is liable to all their penalties, and consequently has a right to

their protection. There is one case I must still mention; some

criminals having escaped execution in Spain, were set free in France.

[Lord Mansfield – Rightly: for the laws of one country have not

whereby to condemn offences supposed to be committed against

those of another.]

An objection has arisen, that the West India Company, with their

trade in slaves, having been established by the law of England, it’s

consequences must be recognized by that law; but the establish-

ment is local, and these consequences local; and not the law of En-

gland, but the law of the Plantations.

The law of Scotland annuls the contract to serve for life; except

in the case of colliers, and one other instance of a similar nature.

A case is to be found in the History of the Decisions, where a

term of years was discharged, as exceeding the usual limits of hu-

man life. At least, if contrary to all these decisions, the court

should include to think Mr. Stewart has a title, it must be by pre-

sumption of contract, there being no deed in evidence; on this sup-

position, Mr. Stewart was obliged, undoubtedly, to apply to a court

of justice. Was it not sufficient, that without form, without written

testimony, without even probability of a parol contract, he should

venture to pretend a right over the person and property of the

negro, emancipated, as we contend, by his arrival hither, at a vast

distance from his native country, while he vainly indulged the natu-

ral expectation of enjoying liberty, where there was no man who

did not enjoy it? Was not this sufficient, but he must still pro-

ceed, seize the unoffending victim, with no other legal pretence

for such a mode of arrest, but the taking an ill advantage of some

inaccurate expressions in the Habeas Corpus Act; and thus pervert

an establishment designed for the perfecting of freedom? I trust, an

exception from a single clause, inadvertently worded, (as I must take

the liberty to remark again) of that one statute, will not be allowed

to over-rule the law of England. I cannot leave the court, without

some excuse for the confusion in which I rose, and in which I now

appear: For the anxiety and apprehension I have expressed, and

deeply felt. It did not arise from want of consideration, for I have

considered this cause for months, I may say years; much less did it

spring from a doubt, how the cause might recommend itself to the

candor and wisdom of the court. But I felt myself over-powered

by the weight of the question. I now, in full conviction how

opposite to natural justice Mr. Stewart‘s claim is, in firm persua-

[6]

sion of it’s inconsistency with the laws of England, submit it chear-

fully to the judgment of this honourable court: And hope as much

honour to your lordships from the exclusion of this new slavery, as

our ancestors obtained by the abolition of the old.

Mr. Alleyne. – Though it may seem presumption in me to offer

any remarks, after the elaborate discourse but now delivered, yet I

hope the indulgence of the court; and shall confine my observations

to some few points, not included by Mr. Hargrave. ‘Tis well

known to your lordships, that much has been asserted by the anci-

ent philosophers and civilians, in defence of the principles of sla-

very: Aristotle has particularly enlarged on that subject. An obser-

vation still it is, of one of the most able, most ingenious, most

convincing writers of modern times, whom I need not hesitate, on

this occasion, to prefer to Aristotle, the great Montesquieu, that

Aristotle, on this subject, reasoned very unlike the philosopher. He

draws his precedents from barbarous ages and nations, and then de-

duces maxims from them, for the contemplation and practice of

civilized times and countries. If a man who in battle has had his

enemy’s throat at his sword’s point, spares him, and says therefore

he has power over his life and liberty, is this true? By whatever

duty he was bound to spare him in battle, (which he always is,

when he can with safety) by the same he obliges himself to spare

the life of the captive, and restore his liberty as soon as possible,

consistent with those considerations from whence he was authorised

to spare at first; the same indispensable duty operates throughout. As

a contract: In all contracts there must be power on one side to

give, on the other to receive; and a competent consideration. Now,

what power can there be in any man to dispose of all the rights

vested by nature and society in him and his descendants? He can-

not consent to part with them, without ceasing to be a man; for

they immediately flow from, and are essential to, his condition as

such: They cannot be taken from him, for they are not his, as a ci-

tizen or a member of society merely; and are not to be resigned to

a power inferior to that which gave them. With respect to consi-

deration, what shall be adequate? As a speculative point, slavery

may a little differ in it’s appearance, and the relation of master and

slave, with the obligations on the part of the slave, may be con-

ceived; and merely in this view, might be thought to take effect

in all places alike; as natural relations always do. But slavery is not

a natural, ’tis a municipal relation; an institution therefore confined

to certain places, and necessarily dropt by passage into a country

where such municipal regulations do not subsist. The negro making

choice of his habitation here, has subjected himself to the penalties,

and is therefore entitled to the protection of our laws. One remark-

able case seems to require being mentioned: Some Spanish criminals

having escaped from execution, were set free in France. [Lord

Mansfield – Note the distinction in the case: In this case, France

[7]

was not bound to judge by the municipal laws of Spain; nor was

to take cognizance of the offences supposed against that law.]

There has been started an objection, that a company having been

established by our government for the trade of slaves, it were unjust

to deprive them here. – No: The government incorporated them

with such powers as individuals had used by custom, the only title on

which that trade subsisted; I conceive, that had never extended, nor

could extend, to slaves brought hither; it was not enlarged at all by

the incorporation of that company, as to the nature or limits of it’s

authority. ‘Tis said, let slaves know they are all free as soon as

arrived here, they will flock over in vast numbers, over-run this

country, and desolate the plantations. There are too strong penal-

ties by which they will be kept in; nor are the persons who might

convey them over much induced to attempt it; the despicable con-

dition in which negroes have the misfortune to be considered, effec-

tually prevents their importation in any considerable degree. Ought

we not, on our part, to guard and preserve that liberty by which we

are distinguished by all the earth! to be jealous of whatever mea-

sure has a tendency to diminish the veneration due to the first of

blessings? The horrid cruelties, scarce credible in recital, perpetrated

in America, might, by the allowance of slaves amongst us, be in-

troduced here. Could your lordship, could any liberal and inge-

nuous temper, endure, in the fields bordering on this city, to see a

wretch bound for some trivial offence to a tree, torn and agonizing

beneath the scourge? Such objects might by time become fami-

liar, become unheeded by this nation; exercised, as they are now, to

far different sentiments, may those sentiments never be extinct! the

feelings of humanity! the generous sallies of free minds! May such

principles never be corrupted by the mixture of slavish customs!

Nor can I believe, we shall suffer any individual living here to want

that liberty, whose effects are glory and happiness to the public and

every individual.

Mr. Wallace – The quesiton has been stated, whether the right

can be supported here; or, if it can, whether a course of proceed-

ings at law be not necessary to give effect to the right? ‘Tis found

in three quarters of the globe, and in part of the fourth. In Asia

the whole people; in Africa and America far the greater part; in

Europe great numbers of the Russians and Polanders. As to capti-

vity in war, the Christian princes have been used to give life to the

prisoners; and it took rise probably in the Crusades, when they gave

them life, and sometimes enfranchised them, to enlist under the

standard of the cross, against the Mahometans. The right of a con-

queror was absolute in Europe, and is in Africa. The natives are

brought from Africa to the West Indies; purchase is made there, not

because of positive law, but there being no law against it. It can-

not be in consideration by this or any other court, to see, whether

the West India regulations are the best possible; such as they are,

[8]

while they continue in force as laws, they must be adhered to. As

to England, not permitting slavery, there is no law against it; nor

do I find any attempt has been made to prove the existence of one.

Villenage itself has all but the name. Tho’ the dissolution of mo-

nasteries, amongst other material alterations, did occasion the decay

of that tenure, slaves could breathe in England: For villains were in

this country, and were mere slaves, in Elizabeth. Sheppard‘s Abridg-

ment, afterwards, says they were worn out in his time. [Lord

Mansfield mentions an assertation, but does not recollect the author,

that two only were in England in the time of Charles the 2d. at the

time of the abolition of tenures.] In the cases cited, the two first

directly affirm an action of trover, an action appropriated to mere

common chattels. Lord Holt‘s opinion, is a mere dictum, a deci-

sion unsupported by precedent. And if it be objected, that a proper

action could not be brought, ’tis a known and allowed practice in

mercantile transactions, if the cause arises abroad, to lay it within

the kingdom: Therefore the contract in Virginia might be laid to

be in London, and would not be traversable. With respect to the

other cases, the particular mode of action was alone objected to;

had it been an action per quod servitium amisit, for loss of service,

the court would have allowed it. The court called the person, for

the recovery of whom it was brought, a slavish servant, in Chamber-

layne‘s case. Lord Hardwicke, and the afterwards Lord Chief Justice

Talbot, then Attorney and Solicitor-General, pronounced a slave not

free by coming into England. ‘Tis necessary the masters should

bring them over; for they cannot trust the whites, either with the

stores or the navigating the vessel. Therefore, the benefit taken on

the Habeas Corpus Act ought to be allowed.

Lord Mansfield observes, The case alluded to was upon a petition in

Lincoln`s Inn Hall, after dinner; probably, therefore, might not, as he

believes the contrary is not usual at that hour, be taken with much

accuracy. The principal matter was then, on the earnest solicitation

of many merchants, to know, whether a slave was freed by being

made a Christian? And it was resolved, not. ‘Tis remarkable,

tho’ the English took infinite pains before to prevent their slaves

being made Christians, that they might not be freed, the French

suggested they must bring their’s into France, (when the edict of

1706 was petitioned for,) to make them Christians. He said, the

distinction was difficult as to slavery, which could not be resumed

after emancipation, and yet the condition of slavery, in it’s full ex-

tent, could not be tolerated here. Much consideration was necessary,

to define how far the point should be carried. The court must

consider the great detriment to proprietors, there being so great a

number in the ports of this kingdom, that many thousands of

pounds would be lost to the owners, by setting them free. (A gen-

tleman observed, no great danger; for in a whole fleet, usually, there

would not be six slaves.) As to France, the case stated decides no

[9]

farther than that kingdom; and there freedom was claimed, be-

cause the slave had not been registered in the port where he en-

tered, conformably to the edict of 1706. Might not a slave as well

be freed by going out of Virginia to the adjacent country, where

there are no slaves, if change to a place of contrary custom was

sufficient? A statute by the legislature, to subject the West India pro-

perty to payment of debts, I hope, will be thought some proof;

another act devests the African Company of their slaves, and vests

them in the West India Company: I say, I hope these are proofs

the law has interfered for the maintenance of the trade in slaves,

and the transferring of slavery. As for want of application pro-

perly to a court of justice; a common servant may be corrected here

by his master’s private authority. Habeas corpus acknowledges a

right to seize persons by force employed to serve abroad. A right of

compulsion there must be, or the master will be under the ridiculous

necessity of neglecting his proper business, by staying here to have

their service, or must be quite deprived of those slaves he has been

obliged to bring over. The case, as to service for life was not al-

lowed, merely for want of a deed to pass it.

The court approved Mr. Alleyne‘s opinion of the distinction, how

far municipal laws were to be regarded: Instanced the right of

marriage; which, properly solemnized, was in all places the same,

but the regulations of power over children from it, and other cir-

cumstances, very various; and advised, if the merchants thought it

so necessary, to apply to parliament, who could make laws.

Adjourned till that day se’nnight.

Mr. Dunning – ‘Tis incumbent on me to justify Captain Knowles‘s

detainer of the negro; this will be effected, by proving a right in

Mr. Stewart; even a supposed one: For till that matter was deter-

mined, it were somewhat unaccountable that a negro should depart

his service, and put the means out of his power of trying that right

to effect, by a flight out of the kingdom. I will explain what appears

to me the foundation of Mr. Stewart‘s claim. Before the writ of

habeas corpus issued in the present case, there was, and there still is,

a great number of slaves in Africa, (from whence the America plan-

tations are supplied) who are saleable, and in fact sold. Under all

these descriptions is James Somerset. Mr. Stewart brought him over

to England; purposing to return to Jamaica, the negro chose to

depart the service, and was stopt and detained by Captain Knowles,

’till his master should set sail and take him away to be sold in Ja-

maica. The gentlemen on the other side, to whom I impute no

blame, but on the other hand much commendation, have advanced

many ingenious propositions; part of which are undeniably true,

and part (as is usual in compositions of ingenuity) very disputable.

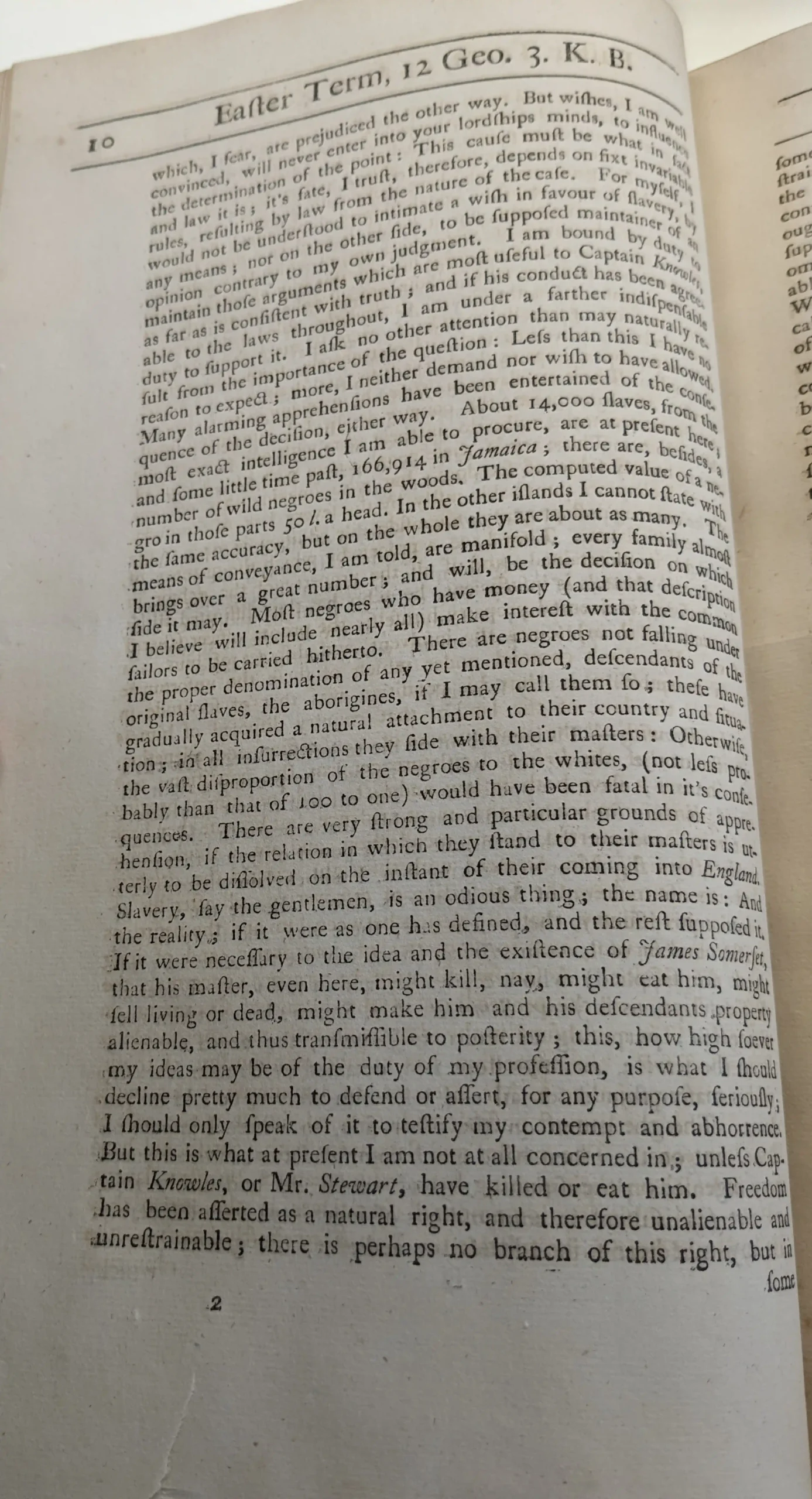

‘Tis my misfortune to address an audience, the greater part of

[10]

which, I fear, are prejudiced the other way. But wishes, I am well

convinced, will never enter into your lordships minds, to influence

the determination of the point: This cause must be what in fact

and law it is; it’s fate, I trust, therefore, depends on fixt invariable

rules, resulting by law from the nature of the case. For myself, I

would not be understood to intimate a wish in favour of slavery, by

any means; nor on the other side, to be supposed maintainer of an

opinion contrary to my own judgment. I am bound by duty to

maintain those arguments which are most useful to Captain Knowles,

as far as is consistent with truth; and if his conduct has been agree-

able to the laws throughout, I am under a farther indispensable

duty to support it. I ask no other attention than may naturally re-

sult from the importance of the question: Less than this I have no

reason to expect; more, I neither demand nor wish to have allowed.

Many alarming apprehensions have been entertained of the conse-

quence of the decision, either way. About 14,000 slaves, from the

most exact intelligence I am able to procure, are at present here;

and some little time past, 166,914 in Jamaica; there are, besides, a

number of wild negroes in the woods. The computed value of a ne-

gro in those parts 50 l. a head. In the other islands I cannot state with

the same accuracy, but on the whole they are about as many. The

means of conveyance, I am told, are manifold; every family almost

brings over a great number; a will, be the decision on which

side it may. Most negroes who have money (and that description

I believe will include nearly all) make interest with the common

sailors to be carried hitherto. There are negroes not falling under

the proper denomination of any yet mentioned, descendants of the

original slaves, the aborigines, if I may call them so; these have

gradually acquired a natural attachment to their country and situa-

tion; in all insurrections they side with their masters: Otherwise,

the vast disproportion of the negroes to the whites, (not less pro-

bably than that of 100 to one) would have been fatal in it’s conse-

quences. There are very strong and particular grounds of appre-

hension, if the relation in which they stand to their masters is ut-

terly to be dissolved on the instant of their coming into England.

Slavery, say the gentlemen, is an odious thing; the name is: And

the reality; if it were as one has defined, and the rest supposed it.

If it were necessary to the idea and the existence of James Somerset,

that his master, even here, might kill, nay, might eat him, might

sell living or dead, might make him and his descendants property

alienable, and thus transmissible to posterity; this, how high soever

my ideas may be of the duty of my profession, is what I should

decline pretty much to defend or assert, for any purpose, seriously;

I should only speak of it to testify my contempt and abhorrence.

But this is what at present I am not at all concerned in; unless Cap-

tain Knowles, or Mr. Stewart, have killed or eat him. Freedom

has been asserted as a natural right, and therefore unalienable and

unrestrainable; there is perhaps no branch of this right, but in

[11]

some at all times, and in all places at different times, has been re-

strained: Nor could society otherwise be conceived to exist. For

the great benefit of the public and individuals, natural liberty, which

consists in doing what one likes, is altered to the doing what one

ought. The gentlemen who have spoke with so much zeal, have

supposed different ways by which slavery commences; but have

omitted one, and rightly; for it would have given a more favour-

able idea of the nature of that power against which they combate.

We are apt (and great authorities support this way of speaking) to

call those nations universally, whose internal police we are ignorant

of, barbarians; (thus the Greeks, particularly, stiled many nations,

whose customs, generally considered, were far more justifiable and

commendable than thier own: ) Unfortunately, from calling them

barbarians, we are apt to think them so, and draw conclusions ac-

cordingly. There are slaves in Africa by captivity in war, but the

number far from great; the country is divided into many small,

some great territories, who do, in their wars with one another, use

this custom. There are of these people, men who have a sense of

the right and value of freedom; but who imagine that offences

against society are punishable justly by the severe law of servitude.

For crimes against property, a considerable addition is made to the

number of slaves. They have a process by which the quantity of

the debt is ascertained; and if all the property of the debtor in

goods and chattels is insufficient, he who has thus dissipated all he

has besides, is deemed property himself; the proper officer (sheriff

we may call him) seizes the insolvent, and disposes of him as a

slave. We don’t contend under which of these the unfortunate

man in question is; but his condition was that of servitude in

Africa; the law of the land of that country disposed of him as

property, with all the consequences of transmission and alienation;

the statutes of the British legislature confirm this condition; and

thus he was a slave both in law and fact. I do not aim at proving

these points; not because they want evidence, but because they have

not been controverted, to my recollection, and are, I think, inca-

pable of denial. Mr. Stewart, with this right, crossed the Atlantic,

and was not to have the satisfaction of discovering, till after his ar-

rival in this country, that all relation between him and the negro, as

master and servant, was to be matter of controversy, and of long

legal disquisition. A few words may be proper, concerning the

Russian slave, and the proceedings of the House of Commons on

that case. ‘Tis not absurd in the idea, as quoted, nor improbable as

matter of fact; the expression has a kind of absurdity. I think,

without any prejudice to Mr. Stewart, or the merits of this cause,

I may admit the utmost possible to be desired, as far as the case of

that slave goes. The master and slave were both, (or should have

been at least) on their coming here, new creatures. Russian slavery,

and even the subordination amongst themselves, in the degree they

use it, is not here to be tolerated. Mr. Alleyne justly observes, the

[12]

municipal regulations of one country are not binding on another;

but does the relation cease where the modes of creating it, the degrees

in which it subsists, vary? I have not heard, nor, I fancy, is there any

intention to affirm, the relation of master and servant ceases here? I

understand the municipal relations differ in different colonies, ac-

cording to humanity, and otherwise. A distinction was endeavoured

to be established betwee natural and municipal relations; but

the natural relations are not those only which attend the person of

the man, political do so too; with which the municipal are most

closely connected: Municipal laws, strictly, are those confined to a

particular place; political, are those in which the municipal laws of

many states may and do concur. The relation of husband and wife,

I think myself warranted in questioning, as a natural relation: Does it

subsist for life, or to answer the natural purposes which may rea-

sonably be supposed often to terminate sooner? Yet this is one of

those relations which follow a man every where. If only natural

relations had that property, the effect would be very limited indeed.

In fact, the municipal laws are principally employed in determining

the manner by which relations are created; and which manner

varies in various countries, and in the same country at different pe-

riods; the political relation itself continuing usually unchanged by

the change of place. There is but one form at present with us, by

which the relation of husband and wife can be constituted; there

was a time when otherwise: I need not say other nations have their

own modes, for that and other ends of society. Contract is not

the only means, on the other hand, of producing the relation of

master and servant; the magistrates are empowered to oblige persons

under certain circumstances to serve. Let me take notice, neither

the air of England is too pure for a slave to breathe in, nor the laws

of England have rejected servitude. Villenage in this country is

said to be worn out; the propriety of the expression strikes me a

little. Are the laws not existing by which it was created? A mat-

ter of more curiosity than use, it is, to enquire when that set of

people ceased. The Statute of Tenures did not however abolish vil-

lenage in gross; it left persons of that condition in the same state as

before; if their descendants are all dead, the gentlemen are right

to say the subject of those laws is gone, but not the law; if the

subject revives, the law will lead the subject. If the statute of

Charles the 2d. ever be repealed, the law of villenage revives in it’s

full force. If my learned brother, the serjeant, or the other gen-

tlemen who argued on the supposed subject of freedom, will go

thro’ an operation my reading assures me will be sufficient for that

purpose, I shall claim them as property. I won’t, I assure them,

make a rigorous use of my power; I will neither sell them, eat

them, nor part with them. It would be a great surprize, and some

incovenience, if a foreigner bringing over a servant, as soon as he

got hither, must take care of his carriage, his horse, and himself,

in whatever method he might have the luck to invent. He must

[13]

find his way to London on foot. He tells his servant, Do this; the

servant replies, Before I do it, I think fit to inform you, Sir, the

first step on this happy land sets all men on a perfect level; you are

just as much obliged to obey my commands. Thus neither supe-

rior, or inferior, both go without their dinner. We should find

singular comfort, on entering the limits of a foreign country, to be

thus at once devested of all attendance and all accommodation.

The gentlemen have collected more reading than I have leisure to

collect, or industry (I must own) if I had leisure: Very laudable

pains has been taken, and very ingenious, in collecting the senti-

ments of other countries, which I shall not much regard, as affect-

ing the point or jurisdiction of this court. In Holland, so far from

perfect freedom, (I speak from knowledge) there are, who without

being conscious of contract, have for offences perpetual labour im-

posed, and death the condition annext to non-performance. Either

all the different ranks must be allowed natural, which is not readily

conceived, or there are political ones, which cease not on change of

soil. But in what manner in the negro to be treated? How far

lawful to detain him? My footman, according to my agreement,

is obliged to attend me from this city, or he is not; if no condition,

that he shall not be obliged to attend, from hence he is obliged,

and no injury done.

A servant of a sheriff, by the command of his master, laid hand

gently on another servant of his master, and brought him before

his master, who himself compelled the servant to his duty; an ac-

tion of assault and battery, and false imprisonment, was brought; and

the principal question was, on demurrer, whether the master could

command the servant, tho’ he might have justified his taking of the

servant by his own hands? The convenience of the public is far

better provided for, by this private authority of the master, than if

the lawfulness of the command were liable to be litigated every

time a servant thought fit to be negligent or troublesome.

Is there a doubt, but a negro might interpose in the defence of a

master, or a master in defence of a negro? If to all purposes of ad-

vantage, mutuality requires the rule to extend to those of disadvan-

tage. ‘Tis said, as not formed by contract, no restraint can be placed

by contract. Which ever way it was formed, the consequences, good

or ill, follow from the relation, not the manner of producing it. I

may observe, there is an establishment, by which magistrates com-

pel idle or dissolute persons, of various ranks and denominations, to

serve. In the case of apprentices bound out by the parish, neither

the trade is left to the choice of those who are to serve, nor the con-

sent of parties necessary; no contract therefore is made in the for-

mer instance, none in the latter; the duty remains the same. The

case of contract for life quoted from the Year-Books, was recog-

nized as valid; the solemnity only of an instrument judged requisite.

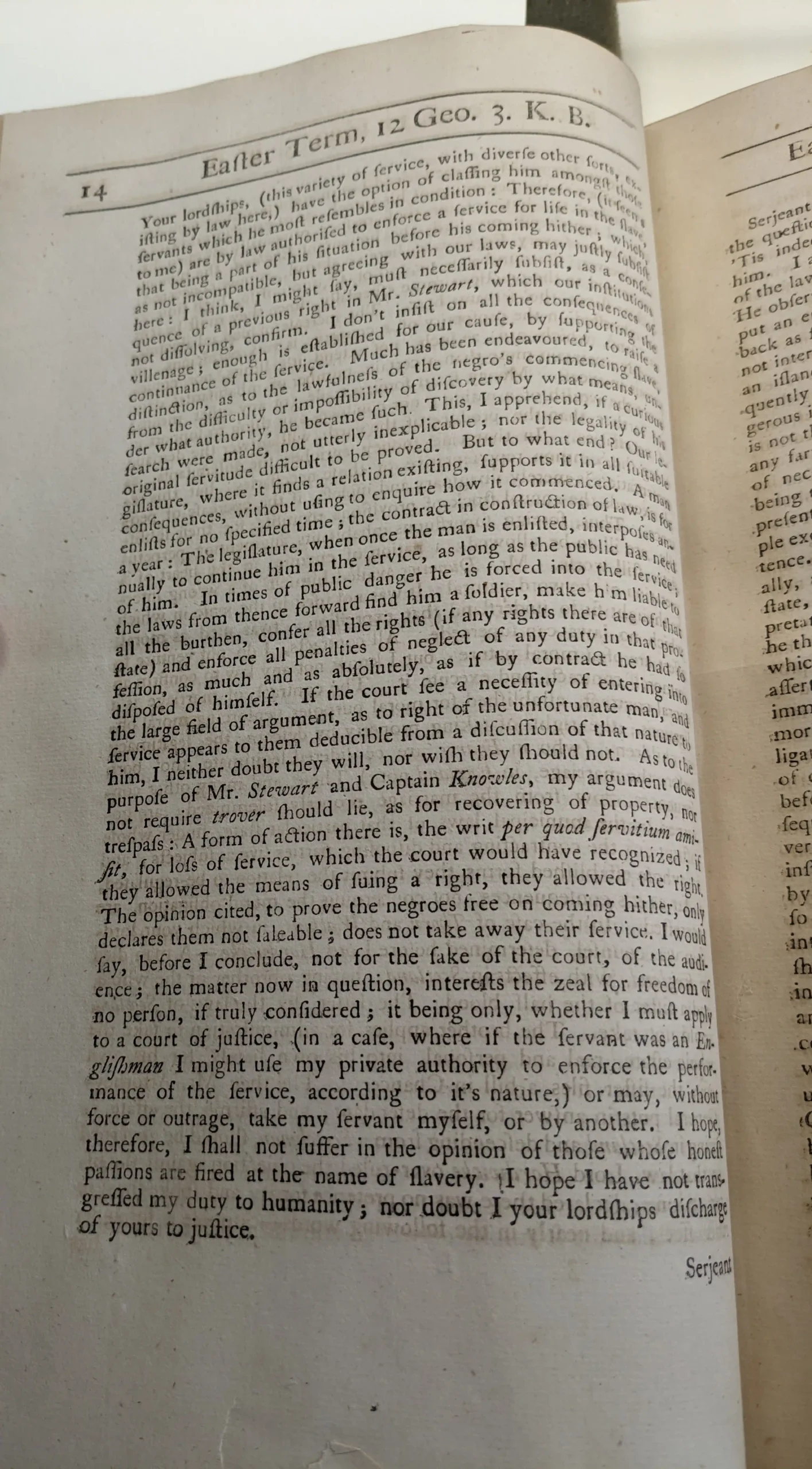

[14]

Your lordships, (this variety of service, with diverse other sorts, ex-

isting by law here,) have the option of classing him amongst those

servants which he most resembles in condition: Therefore, (it seems

to me) are by law authorised to enforce a service for life in the slave,

that being a part of his situation before his coming hither; which,

as not incompatible, but agreeing with our laws, may justly subsist

here: I think, I might say, must necessarily subsist, as a conse-

quence of a previous right in Mr. Stewart, which our institutions

not dissolving, confirm. I don’t insist on all the consequences of

villenage; enough is established for our cause, by supporting the

continuance of the service. Much has been endeavoured, to raise a

distinction, as to the lawfulness of the negro’s commencing slave,

from the difficulty or impossibility of discovery by what means, un-

der what authority, he became such. This, I apprehend, if a curious

search were made, not utterly inexplicable; nor the legality of his

original servitude difficult to be proved. But to what end? Our le-

gislature, where it finds a relation existing, supports it in all suitable

consequences, without using to enquire how it commenced. A man

enlists for no specified time; the contract in construction of law, is for

a year: The legislature, when once the man is enlisted, interposes an-

nually to continue him in the service, as long as the public has need

of him. In times of public danger he is forced into the service;

the laws from thence forward find him a soldier, make him liable to

all the burthen, confer all the rights (if any rights there are of that

state) and enforce all penalties of neglect of any duty in that pro-

fession, as much and as absolutely, as if by contract he had so

disposed of himself. If the court see a necessity of entering into

the large field of argument, as to right of the unfortunate man, and

service appears to them deducible from a discussion of that nature to

him, I neither doubt they will, nor wish they should not. As to the

purpose of Mr. Stewart and Captain Knowles, my argument does

not require trover should lie, as for recovering of property, nor

trespass: A form of action there is, the writ per quod servitium ami-

sit, for loss of service, which the court would have recognized; if

they allowed the means of suing a right, they allowed the right.

The opinion cited, to prove the negroes free on coming hither, only

declares them not saleable; does not take away their service. I would

say, before I conclude, not for the sake of the court, of the audi-

ence; the matter now in question, interests the zeal for freedom of

no person, if truly considered; it being only, whether I must apply

to a court of justice, (in a case, where if the servant was an En-

glishman I must use my private authority to enforce the perfor-

mance of the service, according to it’s nature,) or may, without

force or outrage, take my servant myself, or by another. I hope,

therefore, I shall not suffer in the opinion of those whose honest

passions are fired at the name of slavery. I hope I have not trans-

gressed my duty to humanity; nor doubt I your lordships discharge

of yours to justice.

[15]

Serjeant Davy – My learned friend has thought proper to consider

the question in the beginning of his speech, as of great importance:

‘Tis indeed so; but not for those reasons principally assigned by

him. I apprehend, my lord, the honour of England, the honour

of the laws of every Englishman, here or abroad, is now concerned.

He observes, the number is 14,000 or 15,000; if so, high time to

put an end to the practice; more especially, since they must be sent

back as slaves, tho’ servants here. The increase of such inhabitants,

not interested in the prosperity of a country, is very pernicious; in

an island, which can, as such, not extend it’s limits, nor conse-

quently maintain more than a certain number of inhabitants, dan-

gerous in excess. Money from foreign trade (or any other means)

is not the wealth of a nation; nor conduces any thing to support it,

any farther than the produce of the earth will answer the demand

of necessaries. In that case money enriches the inhabitants, as

being the common representative of those necessaries; but this re-

presentation is merely imaginary and useless, if the encrease of peo-

ple exceeds the annual stock of provisions requisite for their subsis-

tence. Thus, foreign superfluous inhabitants augmenting perpetu-

ally, are ill to be allowed; a nation of enemies in the heart of a

state, still worse. Mr. Dunning availed himself of a wrong inter-

pretation of the word natural: It was not used in the sense in which

he thought fit to understand that expression; ’twas used as moral,

which no laws can supercede. All contracts, I do not venture to

assert are of a moral nature; but I know not any law to confirm an

immoral contract, and execute it. The contract of marriage is a

moral contract, established for moral purposes, enforcing moral ob-

ligations; the right of taking property by descent, the legitimacy

of children; (who in France are considered legitimate, tho’ born

before the marriage, in England not:) These, and many other con-

sequences, flow from the marriage properly solemnized; are go-

verned by the municipal laws of that particular state, under whose

institutions the contracting and disposing parties live as subjects; and

by whose established forms they submit the relation to be regulated,

so far as it’s consequences, not concerning the moral obligation, are

interested. In the case of Thorn and Watkins, in which your lord-

ship was counsel, determined before Lord Hardwicke. – A man died

in England, with effects in Scotland; having a brother of the whole,

and a sister of the half blood: The latter, by the laws of Scotland

could not take. The brother applies for administration to take the

whole estate, real and personal, into his own hands, for his own

use; the sister files a bill in Chancery. The then Mr. Attorney-

General puts in answer for the defendant; and affirms, the estate, as

being in Scotland, and descending from a Scotchman, should be governed

by that law. Lord Hardwicke over-ruled the objection against the sis-

ter’s taking; declared there was no pretence for it; and spoke thus, to

this effect, and nearly in the following words – Suppose a foreigner

[16]

has effects in our stocks, and dies abroad; they must be distributed

according to the laws, not of the place where his effects were, but

of that to which as a subject he belonged at the time of his death.

All relations governed by municipal laws, must be so far dependent

on them, that if the parties change their country the municipal

laws give way, if contradictory to the political regulations of that

other country. In the case of master and slave, being no moral

obligation, but founded on principles, and supported by practice,

utterly foreign to the laws and customs of this country, the law

cannot recognize such relation. The arguments founded on muni-

cipal regulations, considered in their proper nature, have been treated

so fully, so learnedly, and ably, as scarce to offer any room for ob-

servations on that subject: Any thing I could offer to enforce, would

rather appear to weaken the proposition, compared with the strength

and propriety with which that subject has already been explained and

urged. I am not concerned to dispute, the negro may contract to serve;

nor deny the relation between them, while he continues under his

original proprietor’s roof and protection. ‘Tis remarkable, in all

Dyer, for I have caused a search to be made as far as the 4th of

Henry 8th, there is not one instance of a man’s being held a villain

who denied himself to be one; nor can I find a confession of villenage

in those times. [Lord Mansfield, the last confession of villenage

extant, is in the 19th of Henry the 6th.] If the court would ac-

knowledge the relation of master and servant, it certainly would not

allow the most exceptionable part of slavery; that of being obliged

to remove, at the will of the master, from the protection of this

land of liberty, to a country where there are no laws; or hard laws

to insult him. It will not permit slavery suspended for a while,

suspended during the pleasure of the master. The instance of ma-

ster and servant commencing without contract; and that of appren-

tices against the will of the parties, (the latter found in it’s conse-

quences exceedingly pernicious;) both these are provided by special

statutes of our own municipal law. If made in France, or any

where but here, they would not have been binding here. To punish

not even a criminal for offences against the laws of another country;

to set free a galley-slave, who is a slave by his crime; and make a

slave of a negro, who is one, by his complexion; is a cruelty and

absurdity that I trust will never take place here: Such as, if pro-

mulged, would make England a disgrace to all the nations under

earth: For the reducing a man, guiltless of any offence against the

laws, to the condition of slavery, the worst and most abject state,

Mr. Dunning has mentioned, what he is pleased to term philosophi-

cal and moral grounds, I think, or something to that effect, of sla-

very; and would not by any means have us think disrespectfully

of those nations, whom we mistakenly call barbarians, merely for

carrying on that trade: For my part, we may be warranted, I be-

lieve, in affirming the morality or propriety of the practice does not

enter their heads; they make slaves of whom they think fit. For

[17]

the air of England; I think, however, it has been gradually purify-

ing ever since the reign of Elizabeth. Mr. Dunning seems to have

discovered so much, as he finds it changes a slave into a servant;

tho’ unhappily, he does not think it of efficacy enough to prevent

that pestilent disease reviving, the instant the poor man is obliged to

quit (voluntarily quits, and legally, it seems we ought to say,) this

happy country. However, it has been asserted, and is now repeat-

ed by me, this air is too pure for a slave to breathe in: I trust, I

shall not quit this court without certain conviction of the truth of

that assertion.

Lord Mansfield – The question is, if the owner had a right to

detain the slave, for the sending of him over to be sold in Jamaica.

In five or six cases of this nature, I have known it to be accommo-

dated by agreement between the parties: On it’s first coming before

me, I strongly recommended it here. But if the parties will have it

decided, we must give our opinion. Compassion will not, on the one

hand, nor inconvenience on the other, be to decide; but the law:

In which the difficulty will be principally from the inconvenience on

both sides. Contract for sale of a slave is good here; the sale is a

matter to which the law properly and readily attaches, and will

maintain the price according to the agreement. But here the per-

son of the slave himself is immediately the object of enquiry; which

makes a very material difference. The now question is, whether

any dominion, authority or coercion can be exercised in this coun-

try, on a slave according to the American laws? The difficulty of

adopting the relation, without adopting it in all it’s consequences, is

indeed extreme; and yet, many of those consequences are absolutely

contrary to the municipal law of England. We have no authority to

regulate the conditions in which law shall operate. On the other

hand, should we think the coercive power cannot be exercised:

‘Tis now about fifty years since the opinion given by two of the

greatest men of their own or any times, (since which no contract

has been brought to trial, between the masters and slaves; ) the ser-

vice performed by the slaves without wages, is a clear indication

they did not think themselves free by coming hither. The setting

14,000 or 15,000 men at once free loose by a solemn opinion, is

much disagreeable in the effects it threatens. There is a case in Ho-

bart, (Coventry and Woodfall, ) where a man had contracted to go as

a mariner: But the now case will not come within that decision.

Mr. Stewart advances no claim on contract; he rests his whole de-

mand on a right to the negro as slave, and mentions the purpose of

detainure to be the sending of him over to be sold in Jamaica. If

the parties will have judgment, fiat justitia, ruat cœlum, let justice

be done whatever be the consequence. 50 l. a head may not be a

high price; then a loss follows to the proprietors of above 700,000 l.

sterling. How would the law stand with respect to their settle-

ment; their wages? How many actions for any slight coercion by

[18]

the master? We cannot in any of these points direct the law; the

law must rule us. In these particulars, it may be matter of weighty

consideration, what provisions are made or set by law. Mr. Stew-

art may end the question, by discharging or giving freedom to the

negro. I did think at first to put the matter to a more solemn way

of argument: But if my brothers agree, there seems no occasion. I

do not imagine, after the point has been discussed on both sides so

extremely well, any new light could be thrown on the subject. If

the parties chuse to refer it to the Common Pleas, they can give

themselves that satisfaction whenever they think fit. An applica-

tion to parliament, if the merchants think the question of great

commercial concern, is the best, and perhaps the only method of

settling the point for the future. The court is greatly obliged to the

gentlemen of the bar who have spoke on the subject; and by whose

care and abilities so much has been effected, that the rule of decision

will be reduced to a very easy compass. I cannot omit to express

particular happiness in seeing young men, just called to the bar,

have been able so much to profit by their reading. I think it right

the matter should stand over; and if we are called on for a decision,

proper notice shall be given.

Trinity Term, June 22, 1772.

Lord Mansfield – On the part of Somerset, the case which we gave

notice should be decided this day, the court now proceeds to give

it’s opinion. I shall recite the return to the writ of habeas corpus, as

the ground of our determination; omitting only words of form. The

captain of the ship on board of which the negro was taken, makes

his return to the writ in terms signifying that there have been, and

still are, slaves to a great number in Africa; and that the trade in

them is authorized by the laws and opinions of Virginia and Ja-

maica; that they are goods and chattels; and, as such, saleable and

sold. That James Somerset, is a negro of Africa, and long before

the return of the king’s writ was brought to be sold, and was sold

to Charles Stewart Esq. then in Jamaica, and has not been manu-

mitted since; that Mr. Stewart, having occasion to transact busi-

ness, came over hither, with an intention to return; and brought

Somerset, to attend and abide with him, and to carry him back as

soon as the business should be transacted. That such intention has

been, and still continues; and that the negro did remain till the time

of his departure, in the service of his master Mr. Stewart, and quit-

ted it without his consent; and thereupon, before the return of the

king’s writ, the said Charles Stewart did commit the slave on board

the Ann and Mary, to safe custody, to be kept till he should set

sail, and then to be taken with him to Jamaica, and there sold as

a slave. And this is the cause why he, Captain Knowles, who was

then and now is, commander of the above vessel, then and now

lying in the river of Thames, did the said negro, committed to his

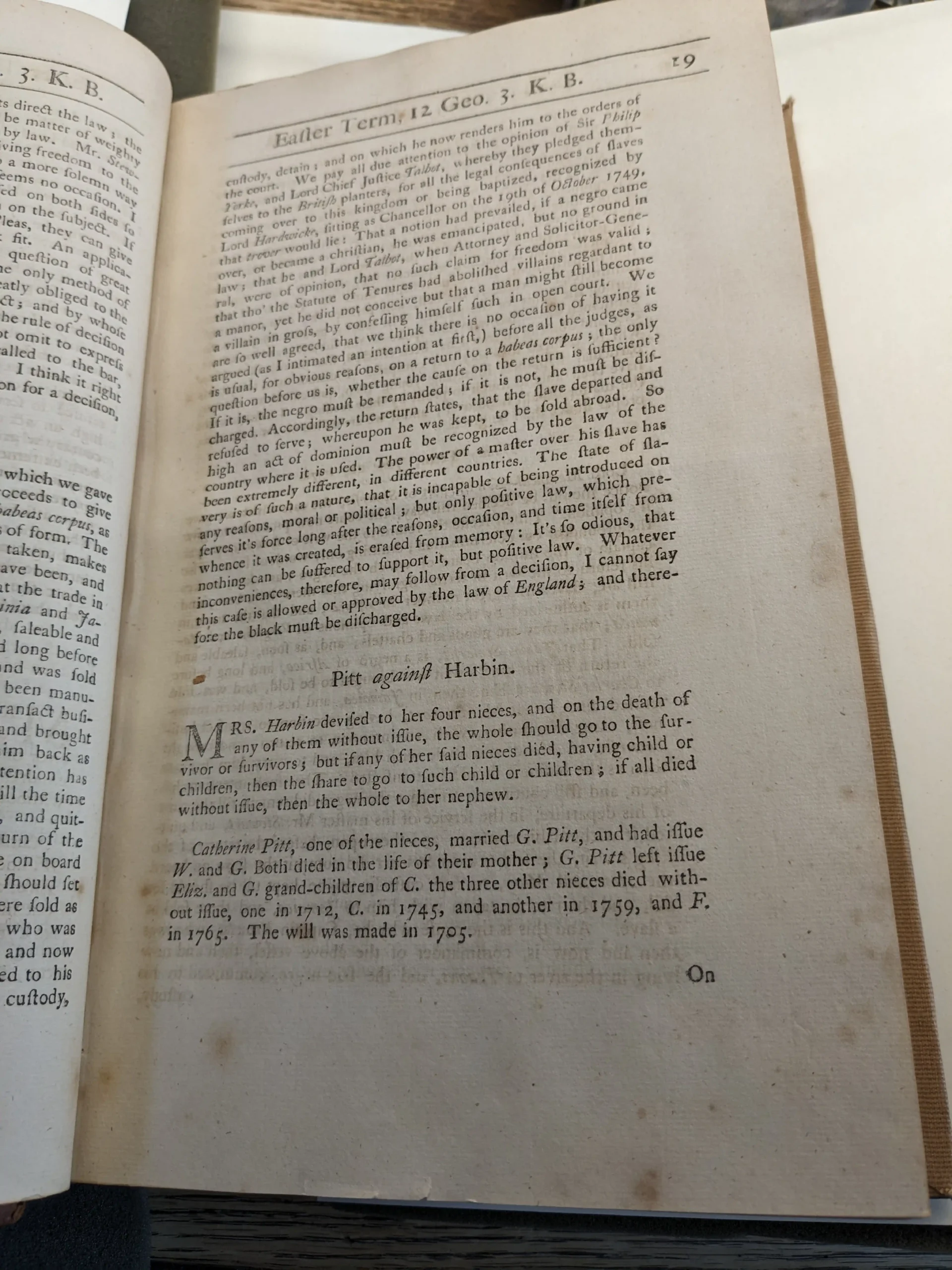

[19]

custody, detain; and on which he now renders him to the orders of

the court. We pay all due attention to the opinion of Sir Philip

Yorke, and Lord Chief Justice Talbot, whereby they pledged them-

selves to the British planters, for all the legal consequences of slaves

coming over to this kingdom or being baptized, recognized by

Lord Hardwicke, sitting as Chancellor on the 19th of October 1749,

that trover would lie: That a notion had prevailed, if a negro came

over, or became a christian, he was emancipated, but no ground in

law; that he and Lord Talbot, when Attorney and Solicitor-Gene-

ral, were of opinion, that no such claim for freedom was valid;

that tho’ the Statute of Tenures had abolished villains regardant to

a manor, yet he did not conceive but that a man might still become

a villain in gross, by confessing himself such in open court. We

are so well agreed, that we think there is no occasion of having it

argued (as I intimated an intention at first,) before all the judges, as

is usual, for obvious reasons, on a return to a habeas corpus; the only

question before us is, whether the cause on the return is sufficient?

If it is, the negro must be remanded; if it is not, he must be dis-

charged. Accordingly, the return states, that the slave departed and

refused to serve; whereupon he was kept, to be sold abroad. So

high an act of dominion must be recognized by the law of the

country where it is used. The power of a master over his slave has

been extremely different, in different countries. The state of sla-

very is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on

any reasons, moral or political; but only positive law, which pre-

serves it’s force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from

whence it was created, is erased from memory: It’s so odious, that

nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever

inconveniences, therefore, may follow from such a decision, I cannot say

this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and there-

fore the black must be discharged.

References

Collections

Tags

Footnotes

- 1Mark S. Weiner. “Notes and Documents: New Biographical Evidence on Somerset’s Case.” Slavery & Abolition 23, no. 1 (2002): 121-136.

- 2Andrew Lyall, ed. Granville Sharp’s Cases on Slavery. (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2017)

- 3William M. Wiecek, “Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American world.” University of Chicago Law Review 42, no. 1 (1974): 86–146; William R. Cotter, “The Somerset Case and the Abolition of Slavery in England.” History, 79, no. 255 (Feb. 1994): 31–56.

- 4David Worrall, “How Much Do We Really Know About Somerset v. Stewart (1772)? The Missing Evidence of Contemporary Newspapers.” Slavery & Abolition 43, no. 3 (2022): 574-593