One Last Try

Corwin Amendment (1860)

On the eve of the Civil War, Thomas Corwin attempted to steer the country in a different direction by offering up a compromise bill that would have protected slavery in the South. By this point, however, the Southern states were willing to except nothing but a full throttled expansion of the institution of slavery.

Introduction

Thomas “The Wagon Boy” Corwin, a Republican congressman from Ohio, introduced this proposed amendment to the Constitution as a last ditch effort to avert the Civil War in December 1860. The Corwin Amendment would have made it impossible for Congress to “abolish or interfere… with the domestic institutions” of the state. The Corwin Amendment was passed by the House by the senate. The 11 states that had at this time already seceded abstained from voting. James Buchanan took the unprecedented act of signing the amendment, even before the states had time to vote on its approval. In his inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln stated that he would endorse the Corwin amendment as a way of saving the Union. Only Kentucky, Ohio, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Illinois voted for its approval, a far cry from the three fourths of states necessary.

Corwin’s amendment was proposed around the same time as John Crittenden’s Compromise. Crittenden was a senator from Kentucky who also wanted to preserve the Union. His proposal was for a whole series of amendments which would have restored a ban on slavery North of the Missouri compromise line, but demand that slavery be secured in the Southwest territories.

Southerners were uninterested in Corwin’s amendment because they felt it did not offer them anything they did not already have. Republicans repeatedly upheld a state’s right to decide the slavery issue where it already existed. Their vision for the end of slavery was to contain the expansion of slavery, until slavery collapsed in on itself from. Republicans conversely flatly rejected Crittenden’s Compromise because it allowed for the Westward expansion of slavery, which would have allowed the resources of slavery to expand and stay economically viable.1James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 47-9.

Refer back to the Constitution, and remember what “domestic institutions refer to”. How does this proposed amendment challenge the power of the federal government to function? How does this proposed amendment close off fundamental access to human rights and the freedom to debate issues?

Justin Hawkins

Further Reading

Sources

- James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 47-9.

- Signed transmittal letter, March 16, 1861, from Abraham Lincoln to Governor John. W. Ellis, North Carolina Digital Collections, p.3, http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p15012coll11/id/611 (Accessed 11/24/17).

Cite this page

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

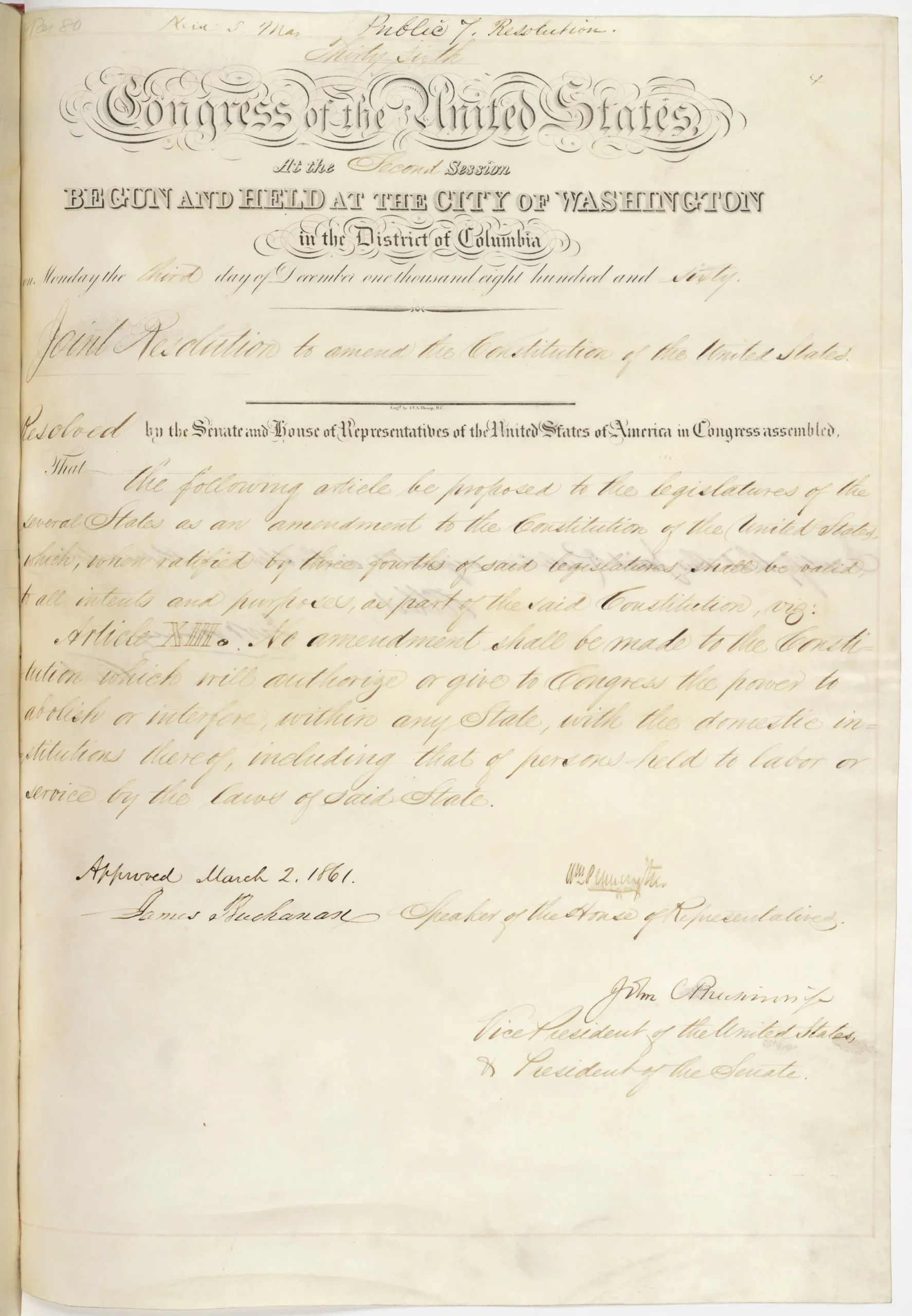

Corwin Amendment (Alternative 13thAmendment not adopted)

THIRTY-SIXTH CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES,

AT THE SECOND SESSION

BEGUN AND HELD AT THE

CITY OF WASHINGTON IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

ON MONDAY THE THIRD DAY OF DECEMBER ONE THOUSAND EIGHT HUNDRED AND SIXTY.

JOINT RESOLUTION to amend the Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several States as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said legislatures, shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the said Constitution, viz:

ARTICLE XIII. No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.

WM. PENNINGTON,

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

JOHN C. BRECKINRIDGE,

Vice-President of the United States,

and President of the Senate.

Approved March 2, 1861.

JAMES BUCHANAN.

References

Collections

Tags

EARLY ACCESS: Transcription is under editorial review and may contain errors.

Please do not cite or otherwise reproduce without permission.

- James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 47-9.

- Signed transmittal letter, March 16, 1861, from Abraham Lincoln to Governor John. W. Ellis, North Carolina Digital Collections, p.3, http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p15012coll11/id/611 (Accessed 11/24/17).

Footnotes

- 1James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 47-9.