Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government

Content Warning

Some of the works in this project contain racist and offensive language and descriptions that may be difficult or disturbing to read. Please take care when reading these materials, and see our Ethics Statement and About page.

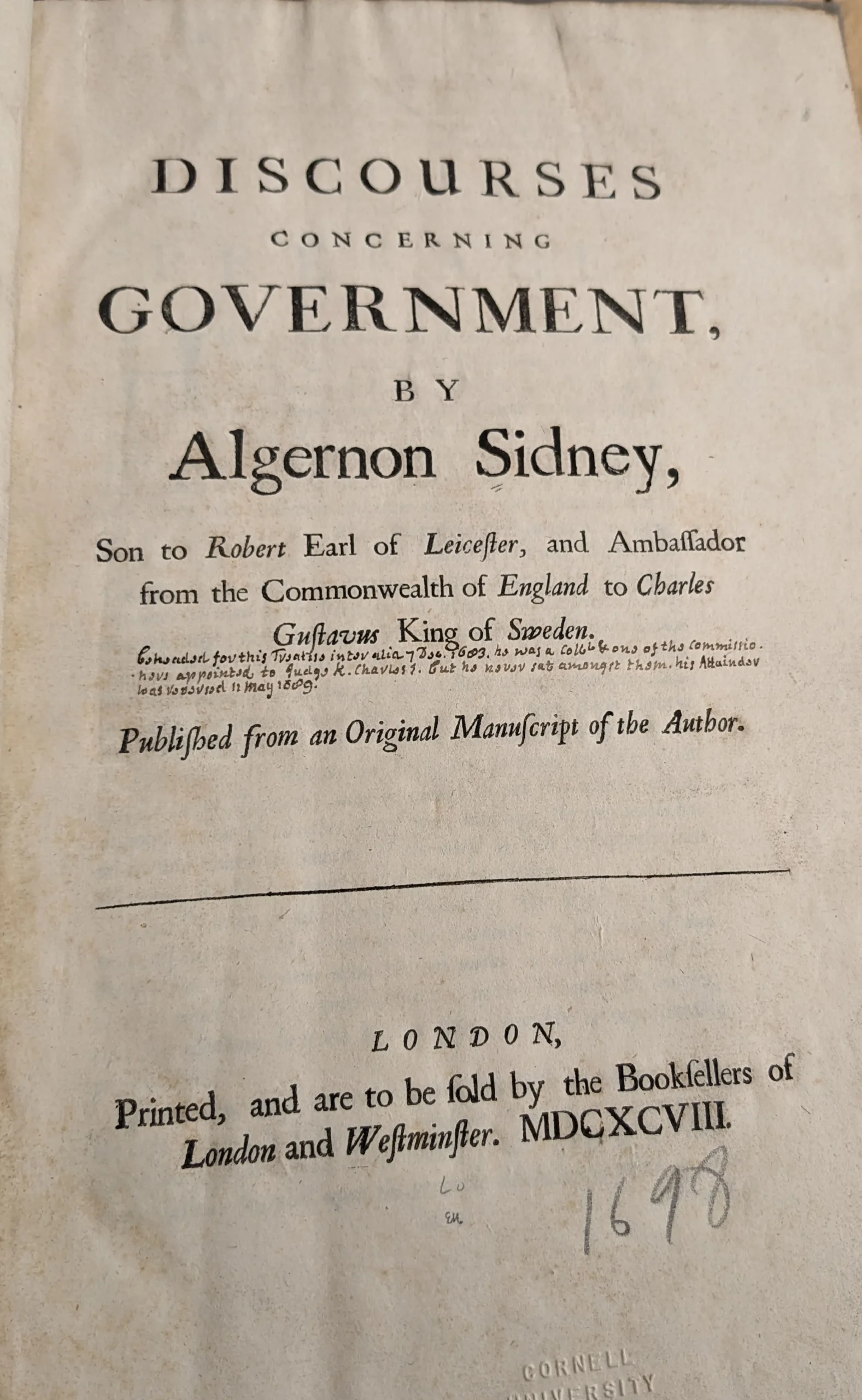

DISCOURSES

CONCERNING

GOVERNMENT,

BY

Algernon Sidney,

Son to Robert Earl of Leicester, and Ambassador

from the Commonwealth of England to Charles

Gustavus King of Sweden.

{beheaded for this Treatise inter allia 7 Dec. 1683, he was a Collonel & one of the Commissio-

nours appointed to Judge K. Charles I. but he never sat amongst them. his Attainder

was reversed 12 May 1689.}

Published from an Original Manuscript of the Author.

LONDON,

Printed, and are to be sold by the Booksellers of

London and Westminster. MDCXCVIII.

{1698}

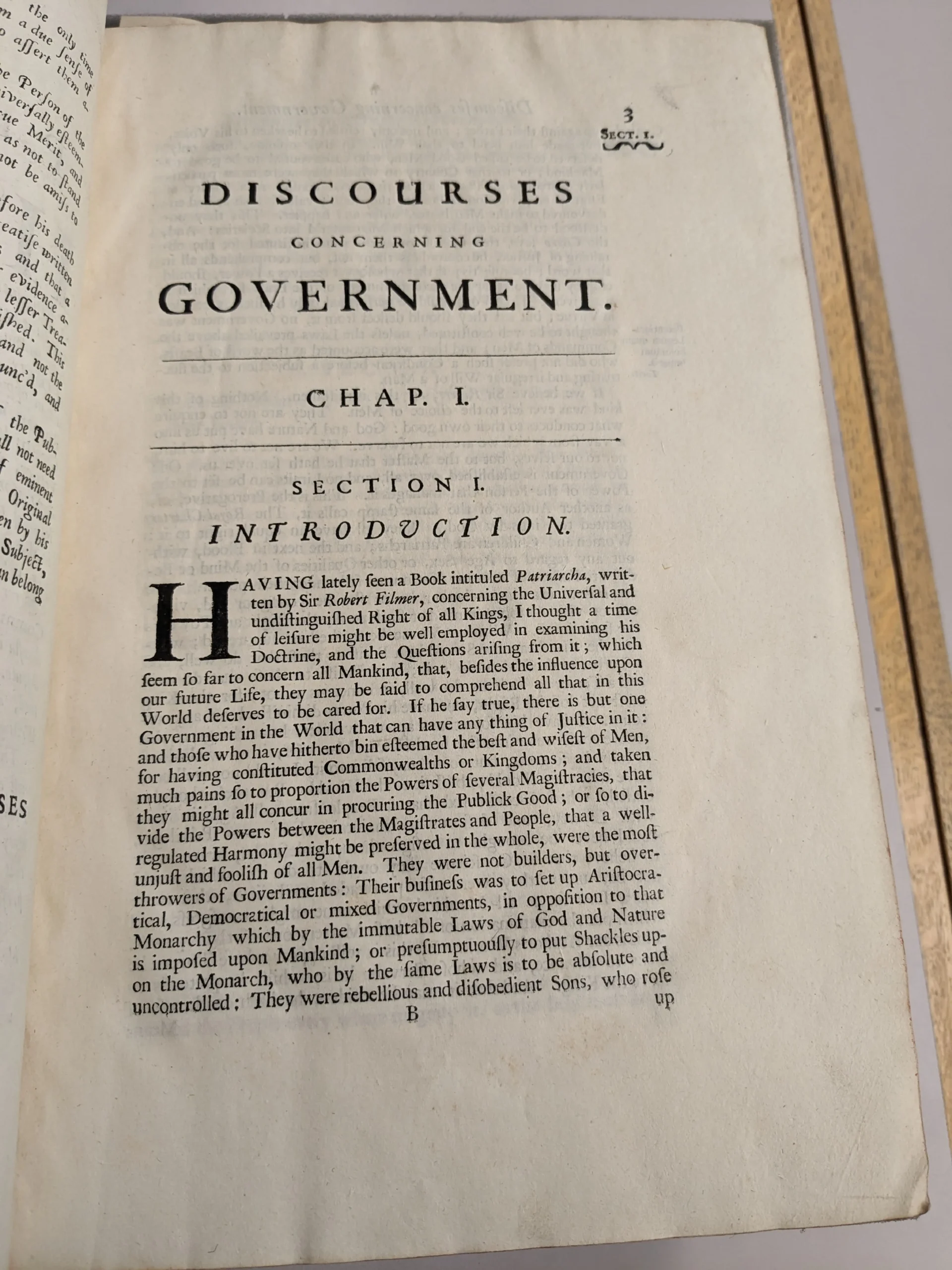

[3]

{SECT. 1.}

DISCOURSES

CONCERNING

GOVERNMENT.

CHAP. I.

SECTION I.

INTRODUCTION.

HAVING lately seen a Book intituled Patriarcha, writ-

ten by Sir Robert Filmer, concerning the Universal and

undistinguished Right of all Kings, I thought a time

of leisure might be well employed in examining his

Doctrine, and the Questions arising from it; which

seem so far to concern all Mankind, that, besides the influence upon

our future Life, they may be said to comprehend all that in this

World deserves to be cared for. If he say true, there is but one

Government in the World that can have any thing of Justice in it:

and those who have hitherto bin esteemed the best and wisest of Men,

for having constituted Commonwealths or Kingdoms; and taken

much pains so to proportion the Powers of several Magistracies, that

they might all concur in procuring the Publick Good; or so to di-

vide the Powers between the Magistrates and People, that a well-

regulated Harmony might be preserved in the whole, were the most

unjust and foolish of all Men. They were not builders, but over-

throwers of Governments: Their business was to set up Aristocra-

tical, Democratical or mixed Governments, in opposition to that

Monarchy which by the immutable Laws of God and Nature

is imposed upon Mankind; or presumptuously to put Shackles up-

on the Monarch, who by the same Laws is to be absolute and

uncontrolled: They were rebellious and disobedient Sons, who rose

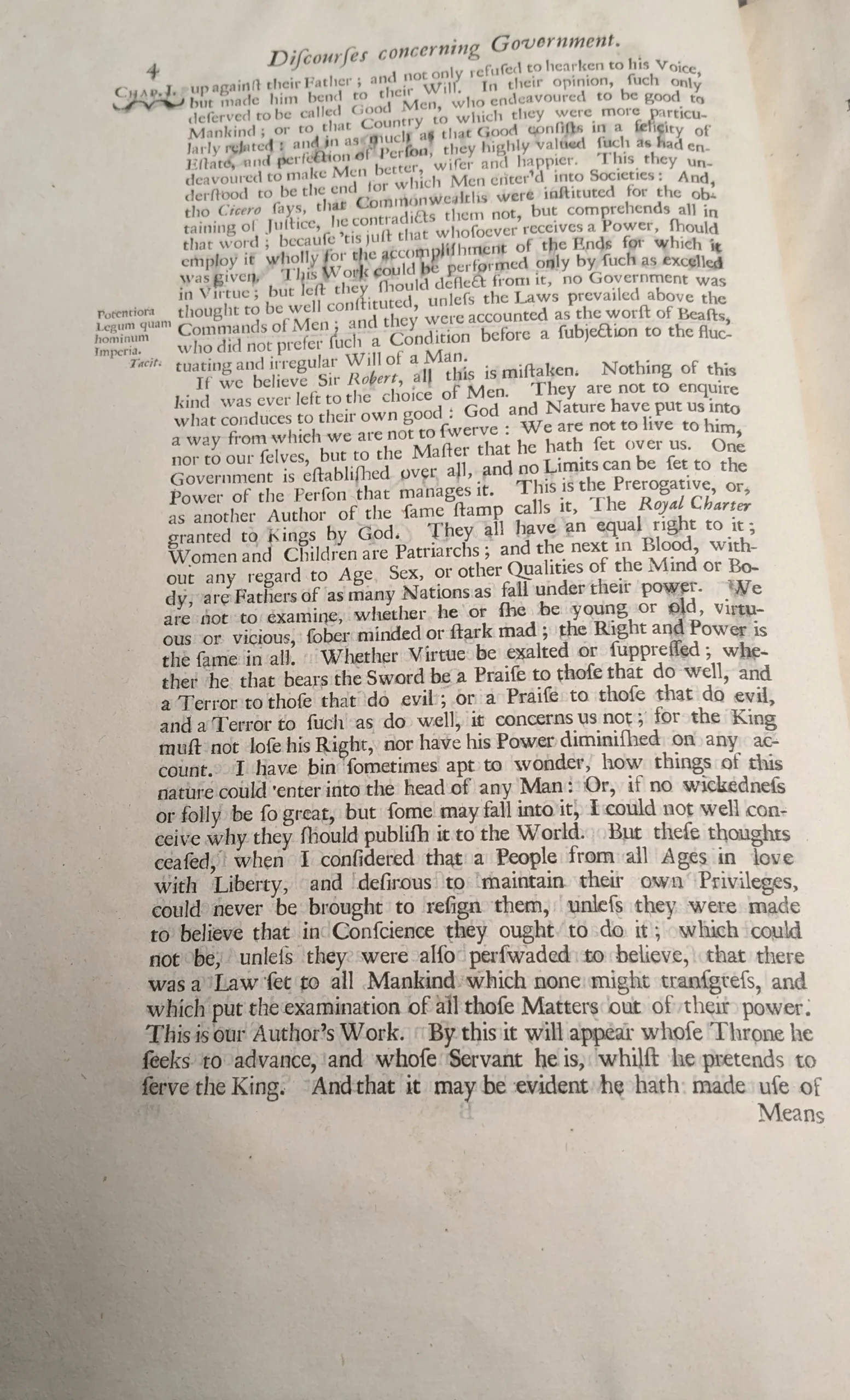

[4]

up against their Father; and not only refused to hearken to his Voice,

but made him bend to their Will. In their opinion, such only

deserved to be called Good Men, who endeavoured to be good to

Mankind; or to that Country to which they were more particu-

larly related: and in as much as that Good consists in a felicity of

Estate, and perfection of Person, they highly valued such as had en-

deavoured to make Men better, wiser and happier. This they un-

derstood to be the end for which Men enter’d into Societies: And,

tho Cicero says, that Commonwealths were instituted for the ob-

taining of Justice, he contradicts them not, but comprehends all in

that word; because ’tis just that whosoever receives a Power, should

employ it wholly for the accomplishment of the Ends for which it

was given. This Work could be performed only by such as excelled

in Virtue; but lest they should deflect from it, no Government was

{Potentiora Legum quam hominum Imperia. Tacit.} thought to be well constituted, unless the Laws prevailed above the

Commands of Men; and they were accounted as the worst of Beasts,

who did not prefer such a Condition before a subjection to the fluc-

tuating and irregular Will of a Man.

If we believe Sir Robert, all this is mistaken. Nothing of this

kind was ever left to the choice of Men. They are not to enquire

what conduces to their own good: God and Nature have put us into

a way from which we are not to swerve: We are not to live to him,

nor to our selves, but to the Master that he hath set over us. One

Government is established over all, and no Limits can be set to the

Power of the Person that manages it. This is the Prerogative, or,

as another Author of the same stamp calls it, The Royal Charter

granted to Kings by God. They all have an equal right to it;

Women and Children are Patriarchs; and the next in Blood, with-

out any regard to Age, Sex, or other Qualities of the Mind or Bo-

dy, are Fathers of as many Nations as fall under their power. We

are not to examine, whether he or she be young or old, virtu-

ous or vicious, sober minded or stark mad; the Right and Power is

the same in all. Whether Virtue be exalted or suppressed; whe-

ther he that bears the Sword be a Praise to those that do well, and

a Terror to those that do evil; or a Praise to those that do evil,

and a Terror to such as do well, it concerns us not; for the King

must not lose his Right, nor have his Power diminished on any ac-

count. I have bin sometimes apt to wonder, how things of this

nature could enter into the head of any Man: Or, if no wickedness

or folly be so great, but some may fall into it, I could not well con-

ceive why they should publish it to the World. But these thoughts

ceased, when I considered that a People from all Ages in love

with Liberty, and desirous to maintain their own Privileges,

could never be brought to resign them, unless they were made

to believe that in Conscience they ought to do it; which could

not be, unless they were also perswaded to believe, that there

was a Law set to all Mankind which none might transgress, and

which put the examination of all those Matters out of their power.

This is our Author’s Work. By this it will appear whose Throne he

seeks to advance, and whose Servant he is, whilst he pretends to

serve the King. And that it may be evident he has made use of

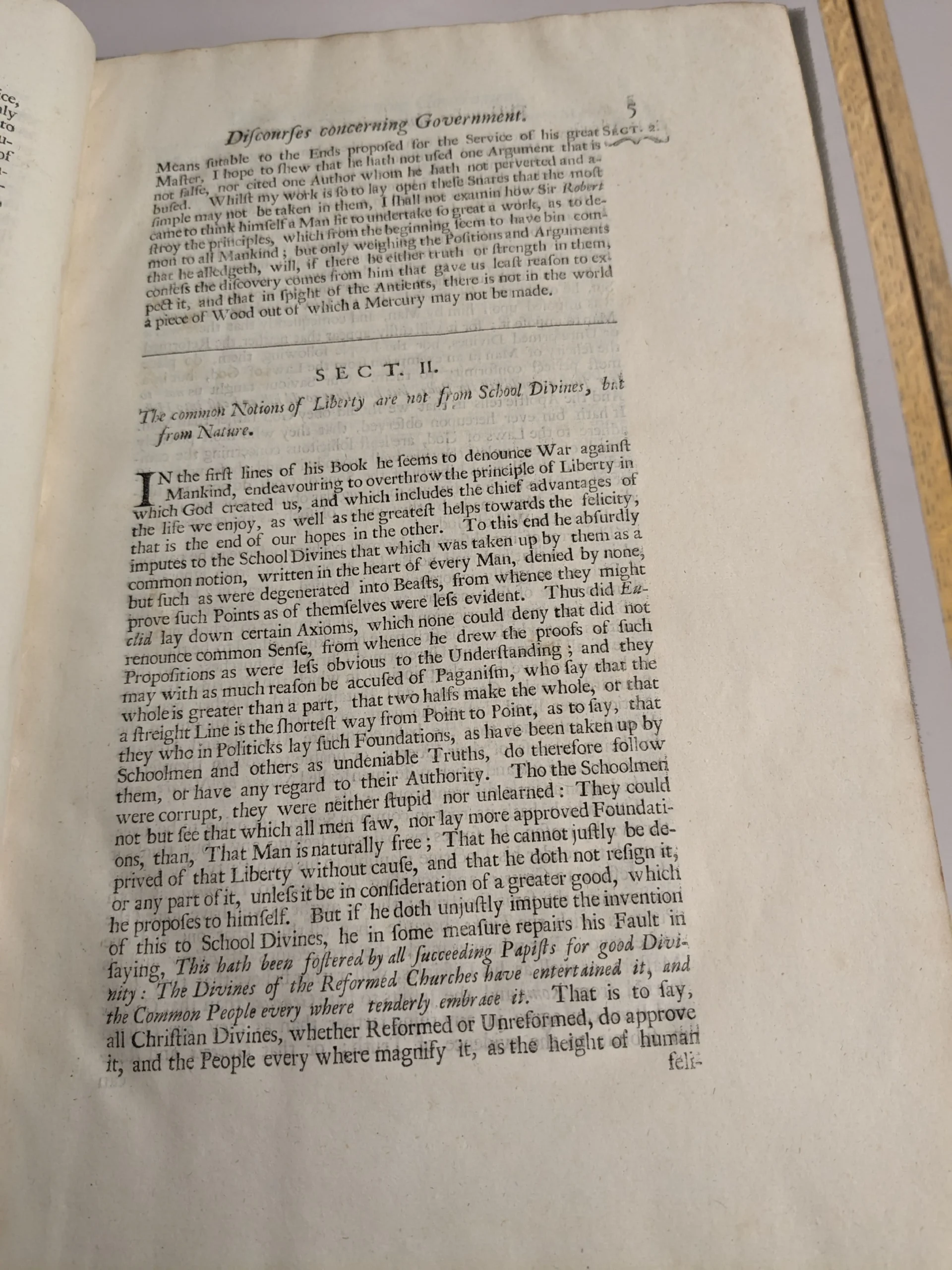

[5]

Means sutable to the Ends proposed for the Service of his great

Master, I hope to shew that he hath not used one Argument that is

not false, nor cited one Author whom he hath not perverted and a-

bused. Whilst my work is so to lay open these Snares that the most

simple may not be taken in them, I shall not examin how Sir Robert

came to think himself a Man fit to undertake so great a work, as to de-

stroy the principles, which from the beginning seem to have bin com-

mon to all Mankind; but only weighing the Positions and Arguments

that he alledgeth, will, if there be either truth or strength in them,

confess the discovery comes from him that gave us least reason to ex-

pect it, and that in spight of the Antients, there is not in the world

a piece of Wood out of which a Mercury may not be made.

[12]

SECT. V.

To depend upon the Will of a Man is Slavery.

THis, as he thinks, is farther sweetned, by asserting, that he

doth not inquire what the rights of a People are, but from

whence; not considering, that whilst he denies they can proceed

from the Laws of natural Liberty, or any other Root than the Grace

and Bounty of the Prince, he declares they can have none at all.

For as Liberty solely consists in an independency upon the Will of a-

nother, and by the name of Slave we understand a man, who can

neither dispose of his Person nor Goods, but enjoys all at the will of

his Master; there is no such thing in nature as a Slave, if those men

or Nations are not Slaves, who have no other title to what they en-

joy, than the grace of the Prince, which he may revoke whensoever

he pleaseth. But there is more than ordinary extravagance in his as-

sertion, That the greatest Liberty in the World is for a People to live under

a Monarch, when his whole Book is to prove, That this Monarch hath

his right from God and Nature, is endowed with an unlimited Pow-

er of doing what he pleaseth, and can be restrained by no Law. If

it be Liberty to live under such a Government, I desire to know what

is Slavery. It has bin hitherto believed in the World, that the Assy-

rians, Medes, Arabs, Egyptians, Turks, and others like them, li-

ved in Slavery, because their Princes were Masters of their Lives and

Goods: Whereas the Grecians, Italians, Gauls, Germans, Spaniards,

and Catthaginians, as long as they had any Strength, Vertue or

Courage amongst them, were esteemed free Nations, because they

abhorred such a Subjection. They were, and would be governed on-

{C. Tacit.} ly by Laws of their own making: Potentiora erant Legum quam homi-

num Imperia. Even their Princes had the authority or credit of per-

swading, rather than the power of commanding. But all this was

mistaken: These men were Slaves, and the Asiaticks were Freemen.

By the same rule the Venetians, Switsers, Grisons, and Hollanders, are

not free Nations: but Liberty in its perfection is enjoyed inFrance,

and Turky. The intention of our Ancestors was, without doubt,

to establish this amongst us by Magna Charta, and other preceding

or subsequent Laws; but they ought to have added one clause, That

the contents of them should be in force only so long as it should please

the King. King Alfred, upon whose Laws Magna Charta was ground-

ed, when he said the English Nation was as free as the internal

thoughts of a Man, did only mean, that it should be so as long as it

pleased their Master. This it seems was the end of our Law,

and we who are born under it, and are descended from such as have so

valiantly defended their rights against the encroachments of Kings,

have followed after vain shadows, and without the expence of Sweat,

[13]

Treasure, or Blood, might have secured their beloved Liberty, by

casting all into the King’s hands.

We owe the discovery of these Secrets to our Author, who after

having so gravely declared them, thinks no offence ought to be taken

at the freedom he assumes of examining things relating to the Liberty

of Mankind, because he hath the right which is common to all:

But he ought to have considered, that in asserting that right to him-

self, he allows it to all Mankind. And as the temporal good of all

men consists in the preservation of it, he declares himself to be a mor-

tal Enemy to those who endeavour to destroy it. If he were alive,

this would deserve to be answered with Stones rather than Words.

He that oppugns the publick Liberty, overthrows his own, and is

guilty of the most brutish of all Follies, whilst he arrogates to him-

self that which he denies to all men.

I cannot but commend his Modesty and Care not to detract from the

worth of learned men; but it seems they were all subject to error, except

himself, who is rendred infallible thro Pride, Ignorance, and Impu-

dence. But if Hooker and Aristotle were wrong in their Fundamentals

concering natural Liberty, how could they be in the right when they

built upon it? Or if they did mistake, how can they deserve to be cited?

or rather, why is such care taken to pervert their sense? It seems

our Author is by their errors brought to the knowledg of the Truth.

Men have heard of a Dwarf standing on the Shoulders of a Giant, who

saw farther than the Giant; but now that the Dwarf standing on the

ground sees that which the Giant did overlook, we must learn from

him. If there be sense in this, the Giant must be blind, or have such

eyes only as are of no use to him. He minded only the things that

were far from him: These great and learned men mistook the very

principle and foundation of all their Doctrine. If we will believe our

Author, this misfortune befel them because they too much trusted to

the Schoolmen. He names Aristotle, and I presume intends to compre-

hend Plato, Plutarch, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius, and all the an-

tient Grecians, Italians, and others, who asserted the natural freedom

of Mankind, only in imitation of the Schoolmen, to advance the pow-

er of the Pope; and would have compassed their design, if Filmer

and his Associates had not opposed them. These men had taught us

to make the unnatural distinction between Royalist and Patriot; and

kept us from seeing, That the relation between King and People is so great;

that their well-being is reciprocal. If this be true, how came Tarquin to

think it good for him to continue King at Rome, when the People

would turn him out? or the People to think it good for them to turn

him out, when he desired to continue in? Why did the Syracusians de-

stroy the Tyranny of Dionysius, which he was not willing to leave,

till he was pulled out by the heels? How could Nero think of burning

Rome? Or why did Caligula wish the People had but one Neck,

that he might strike it off at one blow, if their Welfare was thus

reciprocal? ‘Tis not enough to say, These were wicked or mad men;

for other Princes may be so also, and there may be the same reason of

differing from them. For if the proposition be not universally true, ’tis

not to be received as true in relation to any, till it be particularly pro-

ved; and then ’tis not to be imputed to the quality of Prince, but to the

personal vertue of the Man.

[14]

I do not find any great matters in the passages taken out of Bellar-

min, which our Author says, comprehend the strength of all that

ever he had heard, read, or seen produced for the natural Liberty of

the Subject: but he not mentioning where they are to be found, I do

not think my self obliged to examin all his Works, to see whether they

are rightly cited or not; however there is certainly nothing new in

them: We see the same, as to the substance, in those who wrote many

Ages before him, as well as in many that have lived since his time,

who neither minded him, nor what he had written. I dare not take

upon me to give an account of his Works, having read few of them;

but as he seems to have laid the foundation of his Discourses in such

common Notions as were assented to by all Mankind, those who

follow the same method have no more regard to Jesuitism and Popery,

tho he was a Jesuit and a Cardinal, than they who agree with Faber

and other Jesuits in the principles of Geometry which no sober Man

did ever deny.

[314]

SECT. XV.

A general presumption that Kings will govern well, is not a

sufficient security to the People.

BUT, says our Author, yet will they rule their Subjects by the Law;

and a King governing in a settled Kingdom, leaves to be a King,

and degenerates into a Tyrant, so soon as he ceases to rule according unto

his Laws: Yet where he sees them rigorous or doubtful, he may mitigate or

interpret. This is therefore an effect of their goodness; they are above

Laws, but will rule by Law, we have Filmers‘s word for it. But I

know not how Nations can be assured their Princes will always be so

good: Goodness is always accompanied with Wisdom, and I do not

find those admirable qualites to be generally inherent or entail’d up-

on supreme Magistrates. They do not seem to be all alike, and we

have not hitherto found them all to live in the same Spirit and Princi-

ple. I can see no resemblance between Moses and Caligula, Joshua

and Claudius, Gideon and Nero, Samson and Vitellius, Samuel and

Otho, David and Domitian; nor indeed between the best of these and

their own Children. If the Sons of Moses and Joshua had bin like to

them in wisdom, valour and integrity, ’tis probable they had bin

chosen to succeed them; if they were not, the like is less to be pre-

sumed of others. No man has yet observed the Moderation of Gi-

deon to have bin in Abimelech; the Piety of Eli in Hophni and Phine-

as; the Purity and Integrity of Samuel in Joel and Abiah, nor the

Wisdom of Solomon in Rehoboam. And if there was so vast a difference

between them and their Children, who doubtless were instructed by

those excellent men in the ways of Wisdom and Justice, as well by

Precept as Example, were it not madness to be confident, that they

who have neither precept nor good example to guide them, but on

the contrary are educated in an utter ignorance or abhorrence of all

virtue, will always be just and good; or to put the whole power in-

to the hands of every man, woman, or child that shall be born in

governing Families, upon a supposition, that a thing will happen,

which never did; or that the weakest and worst will perform all that

can be hoped, and was seldom accomplished by the wisest and best,

exposing whole Nations to be destroy’d without remedy, if they do

it not? And if this be madness in all extremity, ’tis to be presumed

that Nations never intended any such thing, unless our Author prove

that all Nations have bin mad from the beginning, and must always

continue to be so. To cure this, he says,They degenerate into Ty-

rants; and if he meant as he speaks, it would be enough. For a King

cannot degenerate into a Tyrant by departing from that Law, which

is only the product of his own will. But if he do degenerate, it

must be by departing from that which dos not depend upon his

will, and is a rule prescribed by a power that is above him. This in-

deed is the Doctrine of Bracton, who having said that the Power of

the King is the Power of the Law, because the Law makes him King,

adds, *Quia si faciat injuriam, definit esse Rex, & degenerat in Tyrannum, & fit vicarius Diaboli. Bract.That if he do injustice, he ceases to be King, degenerates into a

Tyrant, and becomes the Vicegerent of the Devil. But I hope this must

be understood with temperament, and a due consideration of human

frailty, so as to mean only those injuries that are extreme; for other-

wise he would terribly shake all the Crowns of the World.

But lest our Author should be thought once in his life to have dealt

sincerely, and spoken truth, the next lines shew the fraud of his last

Assertion, by giving to the Prince a power of mitigating or interpret-

ing the Laws that he sees to be rigorous or doubtful. But as he cannot de-

generate into a Tyrant by departing from the Law which proceeds from

his own will, so he cannot mitigate or interpret that which proceeds

from a superior Power, unless the right of mitigating or interpreting

be conferred upon him by the same. For as all wise men confess that

+Cujus est instituere, ejus est abrogare. none can abrogate but those who may institute, and that all mitigation

and interpretation varying from the true sense is an alteration, that

alteration is an abrogation; for ||Quicquid mutatur dissolvitur, interit ergò.whatsoever is changed is dissolved,

and therefore the power of mitigating is inseparable from that of

instituting. This is sufficiently evidenced by Henry the Eighth’s An-

swer to the Speech made to him by the Speaker of the House of

Commons 1545, in which he, tho one of the most violent Princes we

ever had, confesses the Parliament to be the Law-makers, and that

an obligation lay upon him rightly to use the power with which he

was entrusted. The right therefore of altering being inseparable

from that of making Laws, the one being in the Parliament, the

other must be so also. Fortescue says plainly, the King cannot

change any Law: Magna Charta casts all upon |||| Leges Terræ & Consuetudines Angliæ. the Laws of the

Land and Customs of England: but to say that the King can by

his will make that to be a Custom, or an antient Law, which is not,

or that not to be so which is, is most absurd. He must therefore

take the Laws and Customs as he finds them, and can neither de-

tract from, nor add any thing to them. The ways are prescribed

as well as the end. Judgments are given by equals, per Pares. The

Judges who may be assisting to those, are sworn to proceed accord-

ing to Law, and not to regard the King’s Letters or Commands. The

doubtful Cases are reserved, and to be referred to the Parliament, as

in the Statute of 35 Edw. 3d concerning Treasons, but never to

the King. The Law intending that these Parliaments should be an-

nual, and leaving to the King a power of calling them more often,

[316]

if occasion require, takes away all pretence of a necessity that there

should be any other power to interpret or mitigate Laws. For ’tis not

to be imagined that there should be such a pestilent evil in any antient

Law, Custom, or later Act of Parliament, which being on the sudden

discover’d, may not without any great prejudice continue for forty days,

till a Parliament may be called; whereas the force and essence of all

Laws would be subverted, if under colour of mitigating and inter-

preting, the power of altering were allow’d to Kings, who often

want the inclination, and for the most part the capacity of doing it

rightly. ‘Tis not therefore upon the uncertain will or understanding

of a Prince, that the safety of a Nation ought to depend. He is

sometimes a child, and sometimes overburden’d with years. Some are

weak, negligent, slothful, foolish or vicious: others, who may have

something of rectitude in their intentions, and naturally are not un-

capable of doing well, are drawn out of the right way by the sub-

tilty of ill men who gain credit with them. That rule must always

be uncertain, and subject to be distorted, which depends upon the

fancy of such a man. He always fluctuates, and every passion that

arises in his mind, or is infused by others, disorders him. The good of

a People ought to be established upon a more solid foundation. For

this reason the Law is established, which no passion can disturb.

‘Tis void of desire and fear, lust and anger. ‘Tis Mens sine affectu,

written reason, retaining some measure of the Divine Perfection.

It dos not enjoin that which pleases a weak, frail man, but without

any regard to persons commands that which is good, and punishes

evil in all, whether rich or poor, high or low. ‘Tis deaf, inexorable,

inflexible.

By this means every man knows when he is safe or in danger, be-

cause he knows whether he has done good or evil. But if all de-

pended upon the will of a man, the worst would be often the most

safe, and the best in the greatest hazard: Slaves would be often ad-

vanced, the good and the brave scorn’d and neglected. The most

generous Nations have above all things sought to avoid this evil: and

the virtue, wisdom and generosity of each may be discern’d by the

right fixing of the rule that must be the guide of every mans life, and

so constituting their Magistracy that it may be duly observed. Such

as have attained to this perfection, have always flourished in virtue

and happiness: They are, as Aristotle says, governed by God, rather

than by men, whilst those who subjected themselves to the will of

a man were governed by a beast.

This being so, our Author’s next clause, That tho a King do frame

all his Actions to be according unto Law, yet he is not bound thereunto,

but as his good will, and for good example, or so far forth as the general

Law for the safety of the Commonwealth doth naturally bind him, is

wholly impertinent. For if the King who governs not according

to Law, degenerates into a Tyrant, he is oblig’d to frame his acti-

ons according to Law, or not to be a King; for a Tyrant is none,

but as contrary to him, as the worst of men is to the best. But if

these obligations were untied, we may easily guess what security our

Author’s word can be to us, that the King of his own good will, and

for a good example, will frame his actions according to the Laws;

[317]

when experience instructs us, that notwithstanding the strictest Laws,

and most exquisite Constitutions, that men of the best abilities in the

world could ever invent to restrain the irregular appetites of those in

power, with the dreadful examples of vengeance taken against such

as would not be restrained, they have frequently broken out; and the

most powerful have for the most part no otherwise distinguished

themselves from the rest of men, than by the enormity of their vices,

and being the most forward in leading others to all manner of crimes

by their example.

[413]

SECT. XXXVI.

The general revolt of a Nation cannot be called a Rebellion.

AS Impostors seldom make lies to pass in the world, without

putting false names upon things, such as our Author endeavour

to perswade the People they ought not to defend their Liberties, by

giving the name of Rebellion to the most just and honourable actions

that have bin performed for the preservation of them; and to ag-

gravate the matter, fear not to tell us that Rebellion is like the sin of

Witchcraft. But those who seek after truth, will easily find, that

there can be no such thing in the world as the rebellion of a Nation

against its own Magistrates, and that rebellion is not always evil.

That this may appear, it will not be amiss to consider the word, as

well as the thing commonly understood by it as it is used in an evil sense.

The word is taken from the Latin rebellare, which signifies no more

than to renew a war. When a Town or Province had bin subdued

by the Romans, and brought under their dominion, if they violated

their Faith after the settlement of Peace, and invaded their Masters

who had spared them, they were said to rebel. But it had bin more

absurd to apply that word to the People that rose against the Decem-

viri, Kings or other Magistrates, than to the Parthians or any of

those Nations who had no dependence upon them; for all the cir-

cumstances that should make a Rebellion were wanting, the word

implying a superiority in them against whom it is, as well as the

breach of an establish’d Peace. But tho every private man singly

taken be subject to the commands of the Magistrate, the whole body

of the People is not so; for he is by and for the People, and the Peo-

ple is neither by nor for him. The obedience due to him from pri-

vate men is grounded upon, and measured by the General Law; and

that Law regarding the welfare of the People, cannot set up the in-

terest of one or a few men against the publick. The whole body

therefore of a Nation cannot be tied to any other obedience than is

consistent with the common good, according to their own judgment:

and having never bin subdued or brought to terms of peace with their

Magistrates, they cannot be said to revolt or rebel against them, to

whom they owe no more than seems good to themselves, and who

are nothing of or by themselves, more than other men.

Again, the thing signified by rebellion is not always evil; for tho

every subdued Nation must acknowledg a superiority in those who

have subdued them, and rebellion do imply a breach of the peace,

yet that superiority is not infinite; the peace may be broken upon just

grounds, and it may be neither a crime nor infamy to do it. The

Privernates had bin more than once subdued by the Romans, and had

{T. Liv. 1. 8.} as often rebelled. Their City was at last taken by Plautius the Con-

sul, after their Leader Vitruvius and great numbers of their Senate

and People had bin kill’d: Being reduced to a low condition, they

sent Ambassadors to Rome to desire peace; where when a Senator

asked them what punishment they deserved, one of them answered,

The same which they deserve who think themselves worthy of Liberty. The

Consul then demanded, what kind of Peace might be expected from them,

if the punishment should be remitted : The Ambassador answer’d, *Si bonam dederitis, fidam & perpetuam; si malam, haud diuturnam. Liv. If

the terms you give be good, the Peace will be observed by us faithfully and

perpetually; if bad, it will soon be broken. And tho some were offended

with the ferocity of the answer; yet the best part of the Senat ap-

proved it as +Viri & liberi vocem auditam. Ibid. worthy of a man and a freeman; and confessing that no

Man or Nation would continue under an uneasy condition longer than

they were compell’d by force, said, ||Eos demum, qui nihil præterquam de libertate cogitant, dignos esse, qui Romani fiant. Ibid. They only were fit to be made

Romans, who thought nothing valuable but Liberty. Upon which

they were all made Citizens of Rome, and obtained whatsoever they

had desired.

I know not how this matter can be carried to a greater height; for

if it were possible, that a People resisting oppression, and vindicating

their own Liberty, could commit a crime, and incur either guilt or

infamy, the Privernates did, who had bin often subdued, and often

pardoned; but even in the judgment of their Conquerors whom they

had offended, the resolution they professed of standing to no agree-

ment imposed upon them by necessity, was accounted the highest

testimony of such a virtue as rendred them worthy to be admitted in-

to a Society and equality with themselves, who were the most brave

and virtuous people of the world.

But if the patience of a conquer’d People may have limits, and

they who will not bear oppression from those who had spared their

Lives, may deserve praise and reward from their conquerors, it would

be madness to think, that any Nation can be obliged to bear whatso-

ever their own Magistrates think fit to do against them. This

may seem strange to those who talk so much of conquests made by

Kings; Immunities, Liberties and Privileges granted to Nations;

Oaths of Allegiance taken, and wonderful benefits conferred upon

them. But having already said as much as is needful concerning

Conquests, and that the Magistrate who has nothing except what

is given to him, can only dispense out of the publick Stock such

Franchises and Privileges as he has received for the reward of Services

done to the Country, and encouragement of Virtue, I shall at pre-

sent keep my self to the two last points.

Allegiance signifies no more (as the words ad legem declare) than

such an obedience as the Law requires. But as the Law can require

nothing from the whole People, who are masters of it, Allegiance

[415]

can only relate to particulars, and not to the whole. No Oath can

bind any other than those who take it, and that only in the true sense

and meaning of it: but single men only take the Oath, and therefore

single men are only obliged to keep it: the body of a People neither

dos, nor can perform any such act: Agreements and Contracts have

bin made; as the Tribe of Judah, and the rest of Israel afterward,

made a Covenant with David, upon which they made him King;

but no wise man can think, that the Nation did thereby make them-

selves the Creature of their own Creature.

The sense also of an Oath ought to be considered. No man can by

an Oath be obliged to any thing beyond, or contrary to the true

meaning of it: private men who swear obedience ad legem, swear

no obedience extra or contra Legem: whatosever they promise or

swear, can detract nothing from the publick Liberty, which the Law

principally intends to preserve. Tho many of them may be obliged

in their several Stations and Capacities to render peculiar services to a

Prince, the People continue as free as the internal thoughts of a man,

and cannot but have a right to preserve their Liberty, or avenge the

violation.

If matters are well examined, perhaps not many Magistrates can

pretend to much upon the title of merit, most especially if they or their

progenitors have continued long in Office. The conveniences annex-

ed to the exercise of the Sovereign power, may be thought sufficient

to pay such scores as they grow due, even to the best: and as things

of that nature are handled, I think it will hardly be found, that all

Princes can pretend to an irresistible power upon the account of be-

neficence to their People. When the family of Medices came to be

masters of Tuscany, that Country was without dispute, in men, mo-

ny and arms, one of the most flourishing Provinces in the World, as

appears by Macchiavel‘s account, and the relation of what happened

between Charles the eighth and the Magistrates of Florence, which

I have mentioned already from Guicciardin. Now whoever shall

consider the strength of that Country in those days, together with

what it might have bin in the space of a hundred and forty years, in

which they have had no war, nor any other plague, than the extortion,

fraud, rapin and cruelty of their Princes, and compare it with their

present desolate, wretched and contemptible condition, may, if he

please, think that much veneration is due to the Princes that govern

them, but will never make any man believe that their Title can be

grounded upon beneficence. The like may be said of the Duke of

Savoy, who pretending (upon I know not what account) that every

Peasant in the Dutchy ought to pay him two Crowns every half

year, did in 1662 subtilly find out, that in every year there were

thirteen halves; so that a poor man who had nothing but what he

gained by hard labour, was through his fatherly Care and Beneficence,

forced to pay six and twenty Crowns to his Royal Highness, to be

employ’d in his discreet and virtuous pleasures at Turin.

The condition of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands (and

even of Spain it self) when they fell to the house of Austria, was of

the same nature: and I will confess as much as can be required, if

any other marks of their Government do remain, than such as

[416]

are manifest evidences of their Pride, Avarice, Luxury and Cru-

elty.

France in outward appearance makes a better show; but nothing

in this world is more miserable, than that people under the fatherly

care of their triumphant Monarch. The best of their condition is

like Asses and Mastiff-dogs, to work and fight, to be oppressed and

kill’d for him; and those among them who have any understand-

ing well know, that their industry, courage, and good success, is

not only unprofitable, but destructive to them; and that by increasing

the power of their Master, they add weight to their own Chains.

And if any Prince, or succession of Princes, have made a more mo-

dest use of their Power, or more faithfully discharged the trust re-

posed in them, it must be imputed peculiarly to them, as a testi-

mony of their personal Virtue, and can have no effect upon o-

thers.

The Rights therefore of Kings are not grounded upon Conquest;

the Liberties of Nations do not arise from the Grants of their Prin-

ces; the Oath of Allegiance binds no privat man to more than the

Law directs, and has no influence upon the whole Body of every

Nation : Many Princes are known to their Subjects only by the in-

juries, losses and mischiefs brought upon them; such as are good and

just, ought to be rewarded for their personal Virtue, but can confer

no right upon those who no way resemble them; and whoever pre-

tends to that merit, must prove it by his Actions : Rebellion being no-

thing but a renewed War, can never be against a Government that

was not established by War, and of it self is neither good nor evil,

more than any other War; but is just or unjust according to the

cause or manner of it. Besides, that Rebellion which by Samuel

{1 Sam. 15.23.} is compar’d to Witchcraft, is not of private men, or a People a-

gainst the Prince, but of the Prince against God : The Israelites are

often said to have rebelled against the Law, Word, or Command of

God; but tho they frequently opposed their Kings, I do not find

Rebellion imputed to them on that account, nor any ill character put

upon such actions. We are told also of some Kings who had bin

subdued, and afterwards rebelled against Chedorlaomer and other

Kings; but their cause is not blamed, and we have some reason to

believe it good, because Abraham took part with those who had re-

belled. However it can be of no prejudice to the cause I defend :

for tho it were true, that those subdued Kings could not justly rise

against the person who had subdued them; or that generally no King

being once vanquished, could have a right of Rebellion against his

Conqueror, it could have no relation to the actions of a people vindi-

cating their own Laws and Liberties against a Prince who violates

them; for that War which never was, can never be renewed. And

if it be true in any case, that hands and swords are given to men,

that they only may be Slaves who have no courage, it must be

when Liberty is overthrown by those, who of all men ought

with the utmost industry and vigour to have defended it.

That this should be known, is not only necessary for the safety of

Nations, but advantagious to such Kings as are wise and good. They

who know the frailty of human Nature, will always distrust their

[417]

own; and desiring only to do what they ought, will be glad to be

restrain’d from that which they ought not to do. Being taught by

reason and experience, that Nations delight in the Peace and Justice

of a good Government, they will never fear a general Insurrection,

whilst they take care it be rightly administred; and finding them-

selves by this means to be safe, will never be unwilling, that

their Children or Successors should be obliged to tread in the same

steps.

If it be said that this may sometimes cause disorders, I acknow-

ledg it; but no human condition being perfect, such as one is to be

chosen, which carries with it the most tolerable inconveniences : And

it being much better that the irregularities and excesses of a Prince

should be restrained or suppressed, than that whole Nations should

perish by them, those Constitutions that make the best provision a-

gainst the greatest evils, are most to be commended. If Govern-

ments were instituted to gratify the lusts of one man, those could

not be good that set limits to them; but all reasonable men confessing

that they are instituted for the good of Nations, they only can de-

serve praise, who above all things endeavour to procure it, and ap-

point means proportioned to that end. The great variety of Go-

vernments which we see in the world, is nothing but the effect of

this care; and all Nations have bin, and are more or less happy, as

they or their Ancestors have had vigour of Spirit, integrity of Man-

ners, and wisdom to invent and establish such Orders, as have better

or worse provided for this common Good, which was sought by all.

But as no rule can be so exact, to make provision against all contesta-

tions; and all disputes about Right do naturally end in force when

Justice is denied (ill men never willingly submitting to any decision

that is contrary to their passions and interests) the best Constitu-

tions are of no value, if there be not a power to support them. This

power first exerts it self in the execution of justice by the ordinary

Officers: But no Nation having bin so happy, as not sometimes to

produce such Princes as Edward and Richard the Seconds, and such

Ministers as Gaveston, Spencer, and Tresilian, the ordinary Officers

of Justice often want the will, and always the power to restrain

them. So that the Rights and Liberties of a Nation must be utter-

ly subverted and abolished, if the power of the whole may not be

employed to assert them, or punish the violation of them. But as it

is the fundamental Right of every Nation to be governed by such

Laws, in such manner, and by such persons as they think most con-

ducing to their own good, they cannot be accountable to any but

themselves for what they do in that most important affair.

Footnotes

- *Si bonam dederitis, fidam & perpetuam; si malam, haud diuturnam. Liv.

- +Viri & liberi vocem auditam. Ibid.

- ||Eos demum, qui nihil præterquam de libertate cogitant, dignos esse, qui Romani fiant. Ibid.

- ||||Leges Terræ & Consuetudines Angliæ.